In less than five years, Keith and Kenny Lucas—better known as The Lucas Bros.—have become an indelible part of a growing list of Black comedic forces. Their roles in 2014’s 22 Jump Street, 2018’s Crashing, and appearances on TV shows like The New Negroes and Sherman’s Showcase have led them to become sought after voices for how they marry the effects of systemic racism with their own humor. “We draw a lot from our biography, our childhood,” Keith divulged in a 2019 chat with CULT-MTL.com. “[We believe] in placing reality in the script.”

As products of inner-city Newark, NJ, the two were originally philosophy grads on their way to becoming lawyers when they discovered the Sklar Brothers (whom they call the “Jackie Robinsons” of twin comedy). Their father had been in jail for 15 years when they were in their adolescence and they used the predicament as a way to turn trauma and anger into triumphant laughter. A chance to work with director Shaka King led to the trio partnering up to pen the story that would become Judas and the Black Messiah.

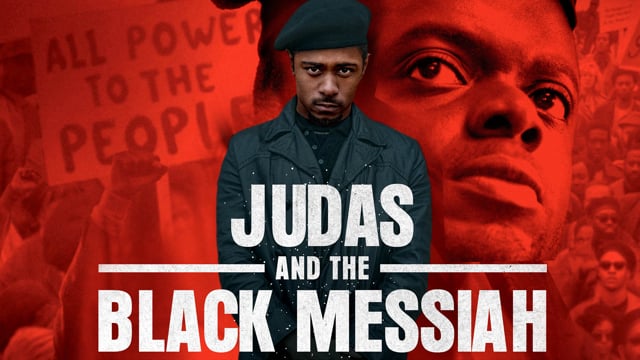

Set in a richly imagined late ’60s Chicago, The Lucas Bros. layer time, perspective, and mood, under the guise of an espionage-esque thriller about the assassination of Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton. With the film already projected high for awards season, Keith and Kenny Lucas are solid contenders for Best Original Screenplay on numerous 2021 Oscar Predictions lists. Their driven purpose is written on the page and only adds to the lessons a new generation can learn as The Lucas Bros. intertwined the timeliness of the past with the current woes happening today.

Judas and the Black Messiah, which will screen first in Tulsa and 13 other satellite cities before its Feb. 12 release to theaters and HBO Max, marks The Lucas Bros. defiant yet cool way to make existential issues relatable and unique. ESSENCE chatted with the twins about how Jesus Was My Homeboy evolved into this powerful and daring film, why the HBO Max deal will launch another Black cinema renaissance, and what the impact of this movie will be with many, presumedly, learning about Chairman Fred Hampton’s story for the first time.

Judas and the Black Messiah is a powerful and daring film, and much has been made of you both penning the story. How did this opportunity come about in a time where we’re all stuck indoors?

KENNY LUCAS: My brother and I have always been students of African-American history. It was going to be my minor in college. We did this course that pretty much analyzed the Civil Rights Movement after Reconstruction up until the late-seventies. We spent some time on [Fred] Hampton [and the Black Panther Party] and it was the first time I had ever heard the name in my life.

When I read his story, I was floored by his life and how the government literally intervened in a way that facilitated and directly caused his death—as an American citizen at that. The story didn’t get much publicity and it wasn’t taught to others like other Black American stories, which struck me as odd. I have to believe that it had to do with the fact that we have direct evidence that the intelligence community conspired to kill a citizen [and] I think they wanted to hide that.

KEITH LUCAS: We were in our third year of law school and decided we didn’t want to be lawyers. We had always been fascinated with cinema, but we didn’t really know how to get anything out. They don’t really teach you how to go from the inner city to Hollywood. You just have to figure it out. As comics, we learned about the industry—how to get movies made, how to pitch movies, how to write your own stories—and it’s not something the studios are going to reach out to get made. You have to literally —

KENNY: Put it out yourself.

KEITH: We were trying to think of the best way to tell this story that will be impactful and sellable. Because, we knew this is a tragic story, and it isn’t one where you go into it thinking you’re going to make a ton of money on it. It isn’t considered “very marketable” in the eyes of corporate America and the studios. We looked at this from another angle, which led us away from the perspective of Fred more to the perspective of William O’Neal, the snitch. It became a genre film, an espionage thriller, which I feel comes across better in the film.

We were fortunate enough to work with Shaka [King] on an earlier pilot for FX. While it didn’t get picked up, we hit it off with him, and his cool and comedic sensibilities just fit with us. When my brother and I went back to our story, we looked at how we all see the world in a similar way, and it just made sense to reach out to him. We wanted this project to feel like a gangster film because we knew that Fred Hampton wasn’t perceived as a civil rights hero in his time. He was vilified. He was demonized by the state and ultimately executed.

In popular culture, Fred Hampton has been immortalized in the creative space by artists like Dave Chappelle, dead prez, and Killer Mike. What do you think Judas and the Black Messiah’s impact will be on audiences who may be learning about the martyr for the first time?

KEITH: In real life, we’ve seen the arbitrary nature of the criminal justice system. You can have a bunch of white guys storm the Capitol, and they’re not vilified and arrested. Some people even treat them as heroes, but you have a person like Hampton, who was exercising his Constitutional rights of free speech, right to bear arms, the right to assembly, and I think the audience will be floored by the story told. I think the audience will get an opportunity to not only learn or re-learn the tragedy of his life, but witness what he was doing by experiencing the world as Fred.

I hope that they feel inspired by his message. I hope that they feel inspired by his commitment to the people, his commitment to uplifting not just the African-American community, but communities across the globe.

KENNY: He had a very global way of thinking, and was so ahead of his time that I just hope that when people watch it they are stunned at how long the federal government has been capable of doing something like this. I hope they take some of that hope that Fred had, despite living in the situation that he lived in, and continue the fight to make a change. It doesn’t matter about age, your socio-economic background, or anything like that. Fred Hampton was an ordinary Black American who had a very, very powerful voice. When people see this iteration of him on screen, I hope the people will be like, ‘Yeah, I can use my voice, too, to make monumental change.’

As writers who are pulling from real world events, how do you feel the imagery of that era resonates with the events we’re experiencing today?

KENNY: We were going through the initial growth of the Black Lives Matter Movement, which played a part in how we saw relevancy in our story. My brother and I felt like we had to get this done and make this film. The protests in Ferguson added more motivation for us to continue, and when the North Police Department were analyzed by the feds, it showed all those continued threads of corruption that our film wanted to explore. To know that Judas was coming out during all these immensely tragic events—George Floyd and Breonna Taylor for example—it was sickening when placed against Hampton’s story which is over 50 years in the making. Now, with this story being released, we’re in the second phase of the Black Lives Matter Movement, and it is surreal.

KEITH: Just adding in that when you see how [former President Donald] Trump’s disregard for the law, and those guys storming the Capitol result in nothing happening to them—it is maddening. They don’t get shot at. They get treated fairly, essentially. They get treated like you’re supposed [to] when you commit crimes—let alone capital offenses. For Black Americans, we don’t get that luxury. We’re tried, trivialized, and executed—all before we can even see a courtroom. Even if we were to come out with this story in 2020, it would have resonated because we’re all seeing the juxtaposition. It’s not just how the state treats Black people, we’re seeing how the state treats white criminals, and that is so jarring when you see how—in Judas and the Black Messiah—that juxtaposition has been happening for so long.

Most have seen The Lucas Bros. perform on screen as comedic actors or on stage as stand-up comics. How does the chemistry between you two help balance humor with speaking truth to power?

KEITH: That’s a great question. We came into the womb together, so I don’t know how to say it, but our natural connection is all about uplift. How can I make my brother better? That’s always been our approach. We would read everything together and talk it out in order to put it together. And I think it has played out that same way with comedy as well. I’m not hesitant to critique him and he’ll tell me when my shit stinks, so, because of that, I feel like it makes our work more honest because neither one of us is holding anything back.

KENNY: It is implied in our philosophical point of view of comedy that we should say things that are historically accurate and speak to the growing movement of Black lives [Matter]. The idea is that in order for us to be recognized as full citizens, we have to treat all people—especially Black people—with the utmost respect. That is embedded in our comedy and even in our approach to drama. I love being Black and I want society to treat all Black people with respect. We have an obligation, in my opinion, to fight on the behalf of those who may not have our outlet, means, or opportunities. I don’t see this as a chore. I see it as an honor to be able to speak to issues that have plagued us since arriving to this country.

It also helps that those means and opportunities are expanding in the name of this Black renaissance happening. Diverting into a bit of shop talk, could you share your respective thoughts about the future of Black cinema via the recent hybrid news regarding HBO Max and movie theaters?

KEITH: We think a lot about Black cinema. This [HBO Max] deal is relatively a new thing [for us] and the industry as a whole. Spike was very huge in ushering us into the modern era, but now, we’re getting a whole host of different voices. Not just Black men. Not just Black women—although people like Issa Rae and—

KENNY: —Ava DuVernay—

KEITH: —And Lena Waithe are excelling on the platform. We’re fighting so hard for these opportunities that it is without fail that we’re in a renaissance. From Queen and Slim to Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom to One Night in Miami, you have so many different films coming out that we’re seeing the Black experience without being mired in tragedy or trauma. There have been a lot of hopeful stories, love stories, and it now feels like we have the space to do everything. We, as filmmakers, can pretty much touch on any and every subject we can imagine.

KENNY: I’m so glad to be a part of it because there is going to be this wave and an artistic force unleashed that will feel unstoppable. No more limitations placed on Black cinema content or the artists regarding box office receipts because films like Get Out and Black Panther prove that Black people do more than just sell big, they change the culture. Now, with those as markers of success, those barriers are really about to be destroyed. I think we’re going to see a lot of Black art that is not just angry, but powerful, and reflects the moods of the country—especially post-Trump. I believe we are about to see an explosion of so many different kinds of art, it is exciting for any of us to be a small part of it.

With Lovecraft Country and Watchmen re-educating viewers to America’s not-so-secret past, it has to be interesting to witness during this media-centric time we’re in. How do you see Judas and the Black Messiah impacting the future of content creation in Hollywood and independent circles?

KENNY: I think what’s great about Black cinema is that we have a lot of stories. As a Black writer, you want to create art that resonates with the culture, but you don’t want something that doesn’t speak to the time. You’re juggling two contradictory thoughts, which is difficult, but there’s always a degree of hopefulness when dealing with Black cinema and art. When we wrote our story, the idea was that we wanted to speak directly to our time, but also explores the topic in a genre that has universal implications.

Kevin L. Clark is a Brooklyn-based freelance writer and curates ESSENCE’s The Playlist. Follow him @KevitoClark.