In 1986 Lorna Simpson created “Waterbearer,” a large-scale photographic work of a woman wearing a white shapeless dress. Her arms are outstretched; her back and shoulders are strong. Her face isn’t shown, only brown skin, straight hair. With her left hand, she pours water from a metal pitcher; with her right she pours water from a plastic jug. The words below the woman say the following: “She saw him disappear by the river, They asked her to tell what happened, Only to discount her memory.”

“Waterbearer” is one of Simpson’s most famous works, and the conceptual artist, now 59, returns to its themes time and again—Black womanhood, life, memory and representation.

When Simpson started making her art, “representation” was not the buzzword it is now. Back then, popular culture reflected a world of Whiteness, heterosexuality and middle-class comfort. However, the Black feminist art of Simpson—along with that of her peers Carrie Mae Weems and Kara Walker— widened this restrictive space, with Simpson’s work being exhibited at or acquired for the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney, Los Angeles’s Museum of Contemporary Art and the Venice Biennale. Now, more than three decades later, Simpson has decided to veer decidedly left in response to a world moving disturbingly right. As she told The New York Times earlier this year, “Dark times, to me, mean dark paintings.” And in a literal interpretation of this belief, she has created a series of pieces for an exhibition titled Darkening.

Life is becoming a heightened, inhospitable condition.

-Lorna Simpson

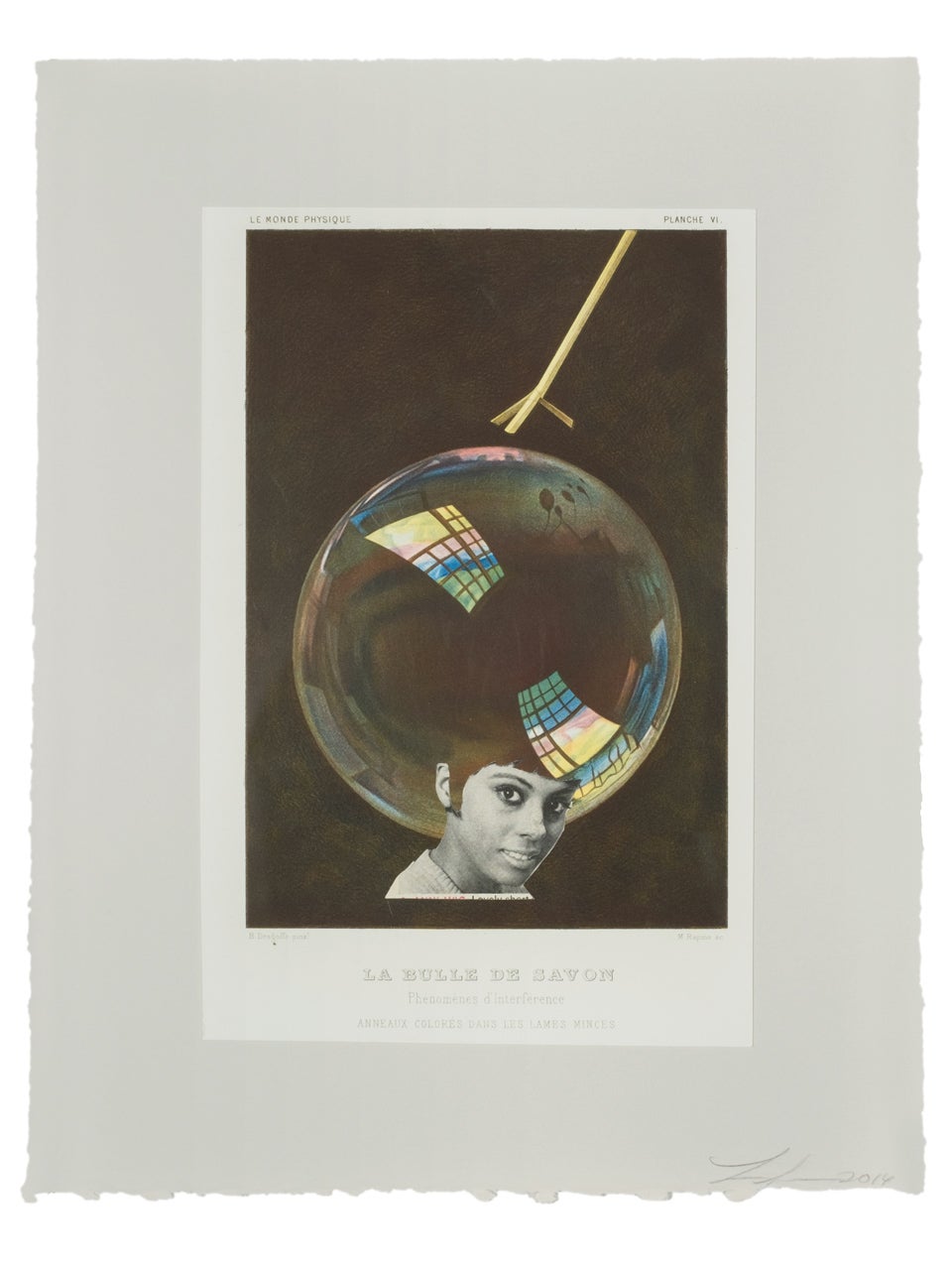

Although there are elements of collage—images from Ebony magazine mixed with old black-and-white photos from Arctic expeditions—these are primarily largescale ink paintings. Simpson, who painted in college, returned to the medium in 2015. Despite their jewel-toned beauty, the paintings depict a place where one would not want to live. Terrains appear uninviting and unstable. Not surprisingly, when discussing the series, Simpson notes that daily life in America is becoming a “heightened, inhospitable condition.” In this new work, she has traded the stark messaging of images like “Waterbearer” for something more abstract but no less bold.

There is also an absence of text. However, the Darkening series is framed by an excerpt from Robin Coste Lewis’s poem “Using Black to Paint Light: Walking Through a Matisse Exhibit, Thinking About the Arctic and Matthew Henson.”

The poem reads in part: “Endless blueness. White is blue. And: It makes me wonder—yet again—was there ever such a thing as whiteness? I am beginning to grow suspicious. An open window.”

For Simpson—who spoke about her series with Thelma Golden, the Studio Museum of Harlem director— the poem is about “memory and time. It’s about place, but it’s contemplating a state of mind as well.”

It’s a powerful description of her work as well.