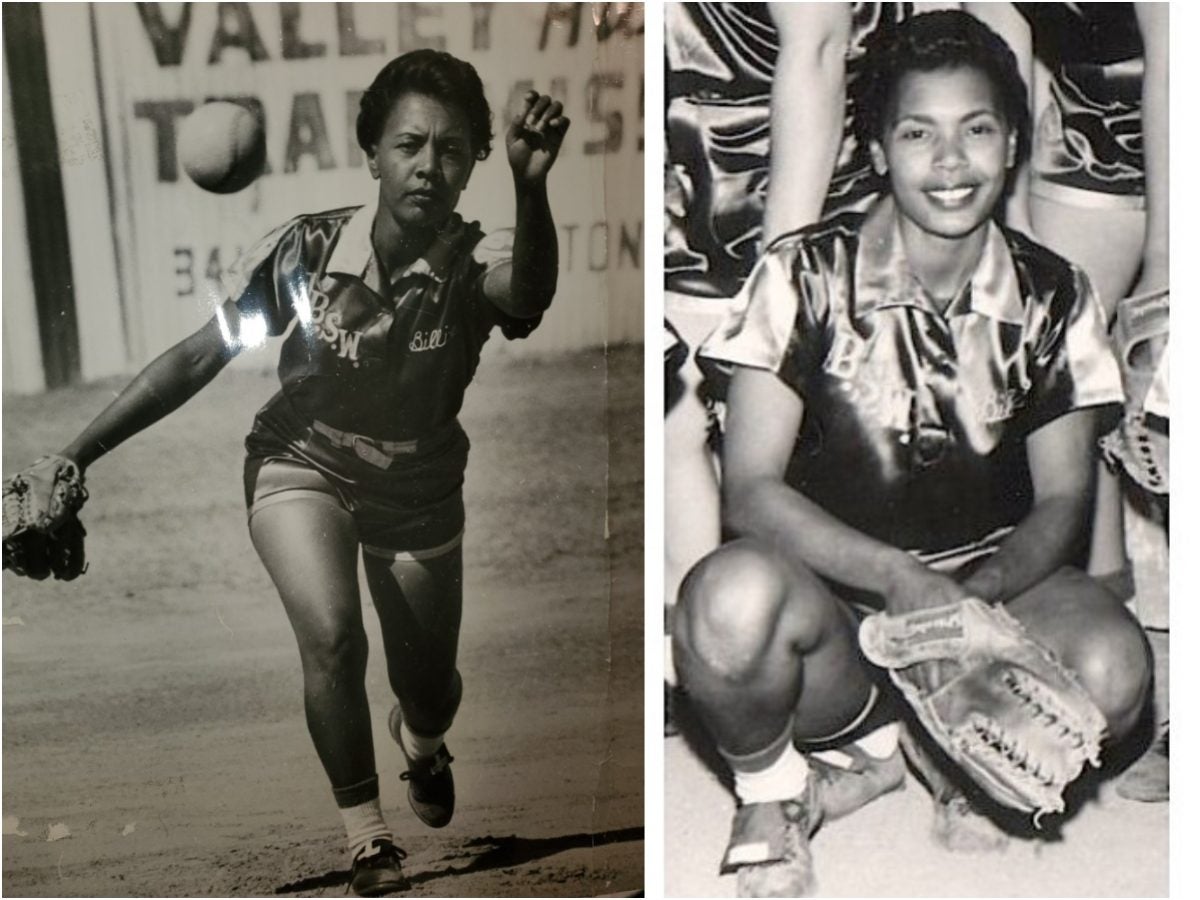

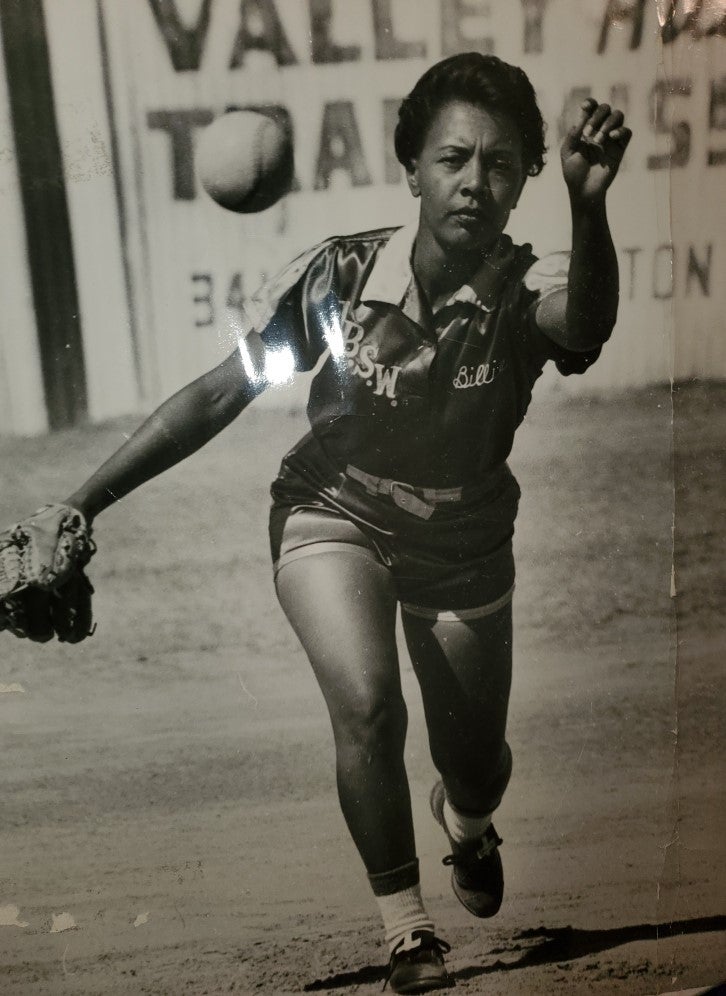

If you’ve been watching A League of Their Own on Prime Video like we have, you’ve probably been curious about the stories of the real-life Black women softball players that inspired characters like Maxine “Max” Chapman, played by Chanté Adams. Billie Harris is one of those women.

Just a teenager when she discovered what she wanted to do with her life, Harris and her family had just moved to Tucson, Arizona from Texas when she stumbled across the local magazine Arizona Highways. In it, she saw a piece about two softball teams: The PVFW Ramblers and the A-1 Queens.

“I said, ‘Oh my, I sure would like to do that.’ And from that moment on, it was just one of those things that I wanted to do,” Harris, 89, tells ESSENCE.

Harris’s discovery came in 1947, the same year Jackie Robinson would integrate Major League Baseball when he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15. A pioneer in the making herself, Harris started practicing the sport she knew she was destined to play. “I used to throw the ball up against the wall,” Harris explains. “I actually did that for hours on end.”

Her dedication paid off. Eventually, someone saw Harris practicing alongside the road and asked her if she’d like to try out. Eagerly accepting the offer, she earned a spot on a team known as The Sunshine Girls.

A left-handed pitcher, Harris spent decades playing softball, including 15 years on The Ramblers, the same team she saw in that magazine as a teen. Her skill on the field led to her being known as “the Jackie Robinson of softball.”

In 370 games, Harris had 264 hits, scored 123 runs and had 59 RBIs (runs batted in). She pitched 70 no-hitters, including four perfect games. Though she would enjoy career success, the journey was not an easy one. Harris was often the only Black woman on her team. And in the 50’s, when she first began playing, segregation was still the law of the land.

“I was not able to eat in the restaurants and if I did eat, I had to eat in the kitchen,” she recalls. Despite the mistreatment, there were always people looking out for Harris. “We had a Black cook in the kitchen so I got the best of food,” she says, chuckling.

Sometimes the hostility existed within her own team. When I ask Harris if her white teammates were welcoming to her at the time, she says, “Some were, some weren’t.”

“I was always the only Black on the team. So it was just one of those things that I had to endure. I wanted to play.”

In addition to the difficult reality of racism, Harris also had to contend with the lack of financial security the comes with being a woman playing a sport. She worked a regular job throughout the early days on the team and she’d often have to decide between softball and gainful employment.

“I had to quit my job every time I had a softball game out of town,” says Harris, who worked in maintenance and eventually at a clothing store in Phoenix. “I would go back early Monday morning to see if they had anything that I could do. Generally, for four years, they did.”

The only compensation Harris received at the beginning of her career was a $3 stipend for food. She wouldn’t play softball on a professional level until she was 43 years old. And then only for a year.

During her years of struggling to be taken seriously, she always had the support of her family. The only girl in the house with four boys, Harris was always known as a tomboy. Her parents, Noble and Arlillian Harris, took her passion for pitching seriously.

“My mother loved it. My dad enjoyed it. My brothers would come to see me play. I was very happy to have my family seeing me.”

In total, Harris played softball for six decades, retiring at the age of 74. “I would have continued except I had knee problems,” she says. “I just thought I’d better quit then.”

Still, she’s gone on record to say she could still run and bend as well as anyone else on the team. Since her retirement, Harris is finally receiving some of the recognition she should have received from the start. In 1979, she was inducted into the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame. And in 1982, surrounded by the family who bolstered her, Harris became the first African American woman inducted into the Amateur Softball Association Hall of Fame.