Country singer Mickey Guyton was brought to tears by the number of Black faces in the audience at Black Music Action Coalition (BMAC)’s Act II:Three Chords and the Actual Truth event in Los Angeles Wednesday evening.

“I’ve been in Nashville for a very long time, and first of all, welcome everybody to country music; great that y’all are finally here,” Guyton told the intimate crowd. “We have been fighting and working so hard to make people realize that Black people are country music. We’ve been working on this for years. I know y’all are here now, but this is before 2020, so I’m trying not to cry seeing all y’all here and seeing the hard work that we’ve done.”

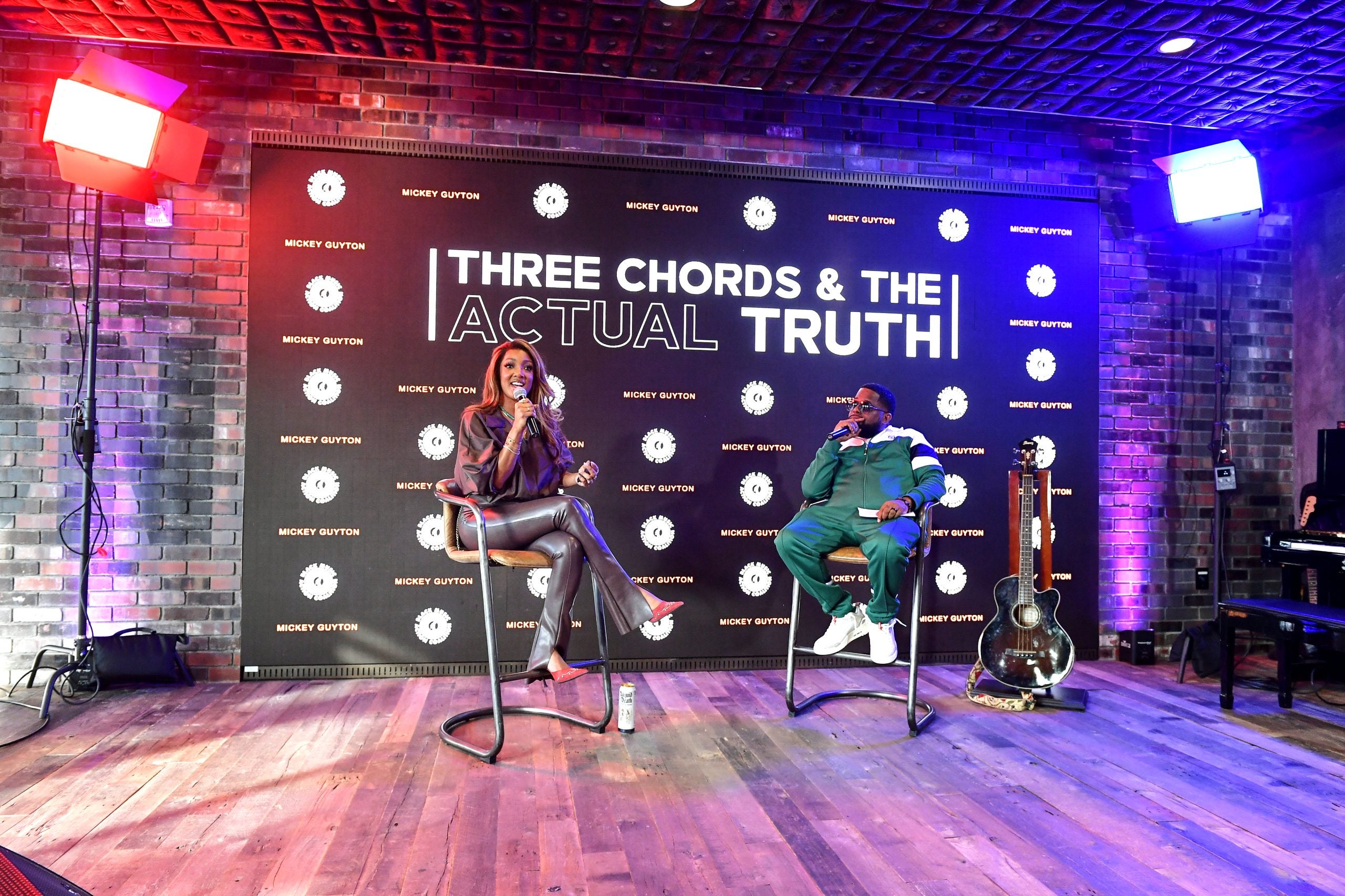

BMAC President and CEO Willie “Prophet” Stiggers kicked off the event centered around the historical exclusion of Black talent from country music despite the origins of the genre in conversation with Guyton who spoke about the realities of the Nashville music scene and the part everyone can play in making it more inclusive by streaming Black country artists’ music and attending their shows.

“We’ve been here before in 2020, in 2017, when we were starting the diversity task force at the ACMs [Academy of Country Music Awards] and trying to figure out how to bring country music to Black people and people of color. They are shuttering the doors on DEI and if we don’t talk about this and be intentional with our consumerism, we’re done. We are actually done,” said Guyton, who spoke about the personal costs of her efforts over the years.

“I’m still healing from a lot of things that were said to me when I was just trying to fight for equality in country music. Nothing more nothing less. I wasn’t telling you who to vote for. I wasn’t telling you anything other than just give people an opportunity not because of anything more than because they’re talented and they deserve the same chances and that comes at a price.”

Guyton’s words echoed that of BMAC Co-founder Caron Veazey who spoke about creating BMAC in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery in 2020 and how the organization’s goal of eradicating racism within the music business has become more difficult in the four years since the industry made a pledge to do better.

“It’s not on the front page like it was in 2020 and we knew that day would come,” said Veazey. “DEI is being dismantled everywhere. So our job is now harder than it was in 2020 in many ways and BMAC really has an even bigger responsibility now. We need everybody’s help, everybody’s attention, and everybody’s support and partnership to continue our mission and really make that difference.”

What support looks like in this moment, Guyton and Stiggers emphasized, is not letting the attention Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter album has placed on both Black country artists and the racism within the country music industry pass.

“When this Beyoncé moment is done and all of her country fans are done with their boots and spurs, these Black country artists that you’re seeing and liking their posts, we will still remain,” said Guyton. “We’re still in predominantly white spaces. I’m still the only Black person in a lot of predominantly white spaces on actual boards trying to help make decisions and at fundraisers. It’s so imperative that every single one of you, Black, white, whatever, show these corporations the monetary value of Black art.”

To further drive home the obstacles Black country music artists face – like Tanner Adell and Tiera Kennedy who were both dropped from their labels before appearing on the Cowboy Carter track “Blackbird”— Dr. Jada Watson, Director of Musicology at the University of Ottawa, broke down the origins of segregation within the music industry and how that specifically impacts the genre of country.

“The recording industry, when it was being developed in the 1920s, was racially segregated—Hillbilly Music and Race Records—and these became classification categories through which music would be recorded and then marketed,” said Dr. Watson on a panel alongside Grammy award-winning artist and songwriter INK as she explained that those same categories later expanded to radio, then the Billboard charts, and now digital streaming platforms (DSPs).

“Every single decision that was made as a way to build the infrastructure and market music has been racially segregated and it is 100 percent still going on today,” she added. “If you think your DSPs are any different, they are not. Because those same classifications of R&B and country, what they are today, have their roots in the 1920s segregated industry.”

What that looks like in numbers, Dr. Watson explained, is that over the past 22 years, songs by Black women represent less than 1% of airplay on country music radio. “Quite often we’re talking 0.03%. In 2023, songs by Black women received 0.02% of airplay so when ‘Texas Hold ‘Em’ came out, this was the opportunity, as far as I was concerned because she comes with such a global audience, for the format to pick up her song and for the industry to build opportunity around it. It hit no. 29 on March 23, and it’s starting to decline, and I have genuine concerns about that,” said Dr. Watson, who noted if you add “Texas Hold ‘Em” to the mix of songs by Black women that are currently receiving airplay the number raises to just 0.24%. “So we’re still not in a great place.”

Emphasizing a point Guyton made earlier in the evening about the impact that could be made “If every Beyoncé fan would just stream our song one time,” Dr. Watson said it’s not enough to simply like and follow Black country music artists on social or streaming platforms.

“It’s one thing to go over and follow, it’s another thing to, as Mickey was saying, keep listening, keep streaming, come back, listen to new songs, listen to old songs, because that conversion rate is negative right now,” she said. “On the one hand, it’s fine because there’s still a rise in followers, but that’s going to plateau when Beyoncé moves on to Act III, so Mickey’s advice, to me, was the best advice. Actually go and stream them consistently, stay with them, follow them, go to their shows, buy their merch.”

As long as the road ahead to equality for Black artists across all music genres may be, both Guyton and BMAC said they refuse to stop trying.

“Our goal with BMAC is to be non-existent,” said Stiggers, indicating a dissolution of the organization would mean racism within the music industry has indeed been eradicated.

Speaking to the journey ahead, Guyton added, “We may not see the true change that we want to see in our lifetime, but this right here gives me so much hope.”