This Friday, Kevin MacDonald’s acclaimed 2012 documentary film Marley will be re-released via virtual cinemas and drive-ins across the country as part of the year-long celebration of Bob Marley’s 75th anniversary. According to film’s distributor Blue Fox Entertainment, information about digital screenings of Marley can be found on MarleyMovie.com starting July 31. (Appropriately enough, Jamaica celebrates Emancipation Day on August 1, one day after the film’s re-release.)

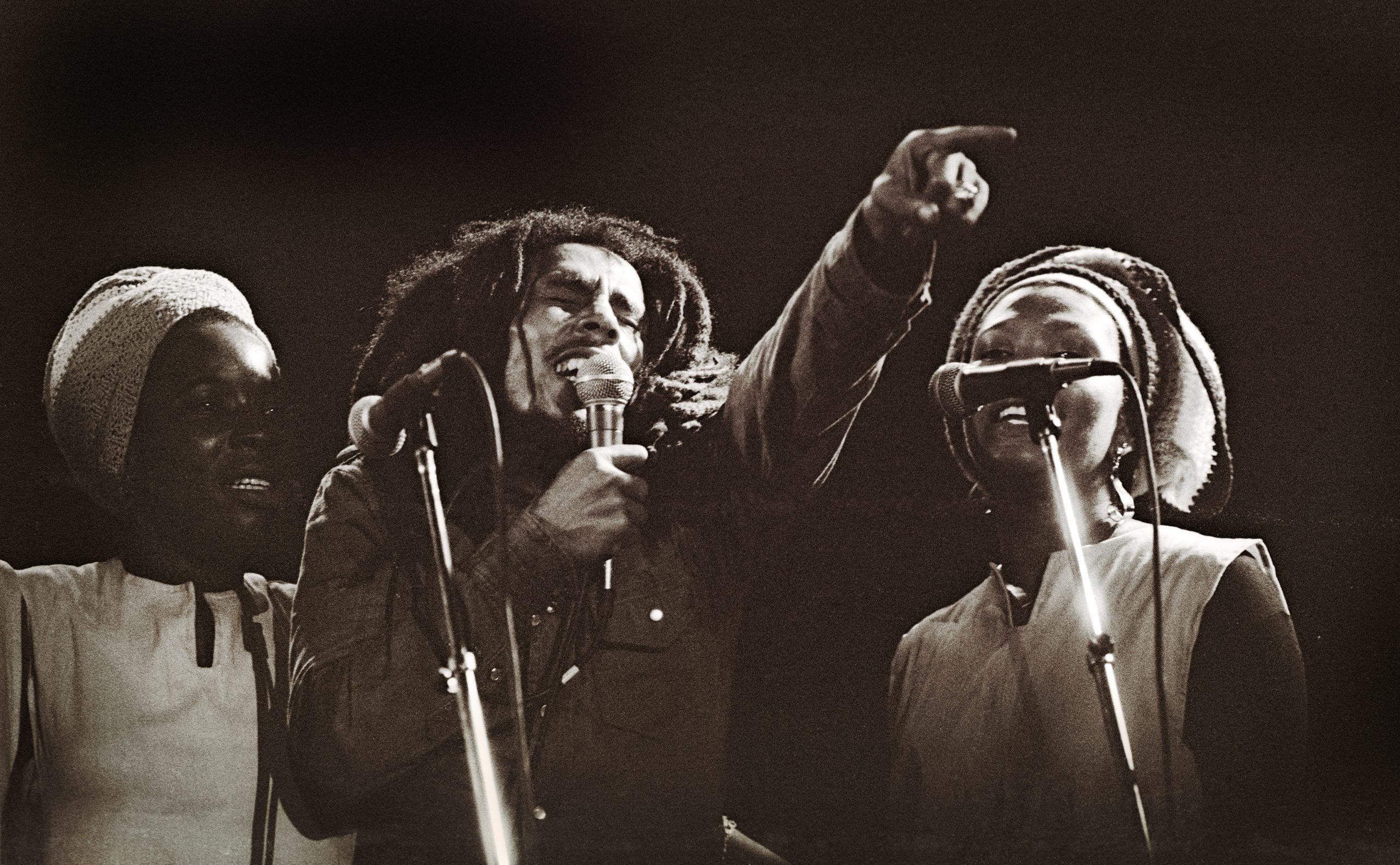

The emotional and inspiring story follows Robert Nesta Marley from his upbringing in the rural Jamaican village of Nine Mile through his journey to Kingston’s tough Trenchtown neighborhood, where his musical career began. Featuring rare concert footage and exclusive interviews with Marley’s family and close friends, MacDonald’s goal was to get behind the legend and show us Marley the man.

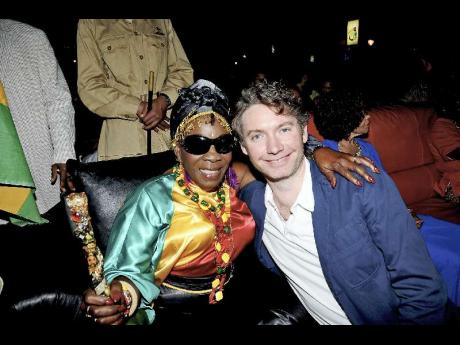

At Marley‘s Jamaican premiere at Kingston’s Emancipation Park in April 2012, I was one of the privileged few who attended the special screening that was open to the public. There were many VIP guests, including his wife Rita Marley to Island Records founder Chris Blackwell, who signed Marley to an international record deal, and of course Kevin MacDonald himself.

“In this moment of time it’s good for us as Africans and Jamaicans to be here and watch this memorable program tonight,” Rita told the crowd in her opening remarks. “I don’t want to talk too long because Bob has so much things to say. Be prepared because I cried,” she added. “But don’t cry as he said ‘No Woman No Cry.’”

“I think people have a very wrong idea of Bob,” said MacDonald, who called the screening one of the nights of his life. “Everyone thinks he just smoked and the inspiration came to him and he strummed his guitar. No—he worked hard hard hard.” The film also highlighted the fact that Bob’s biracial background led him to be ostracized by some of his fellow Jamaicans.

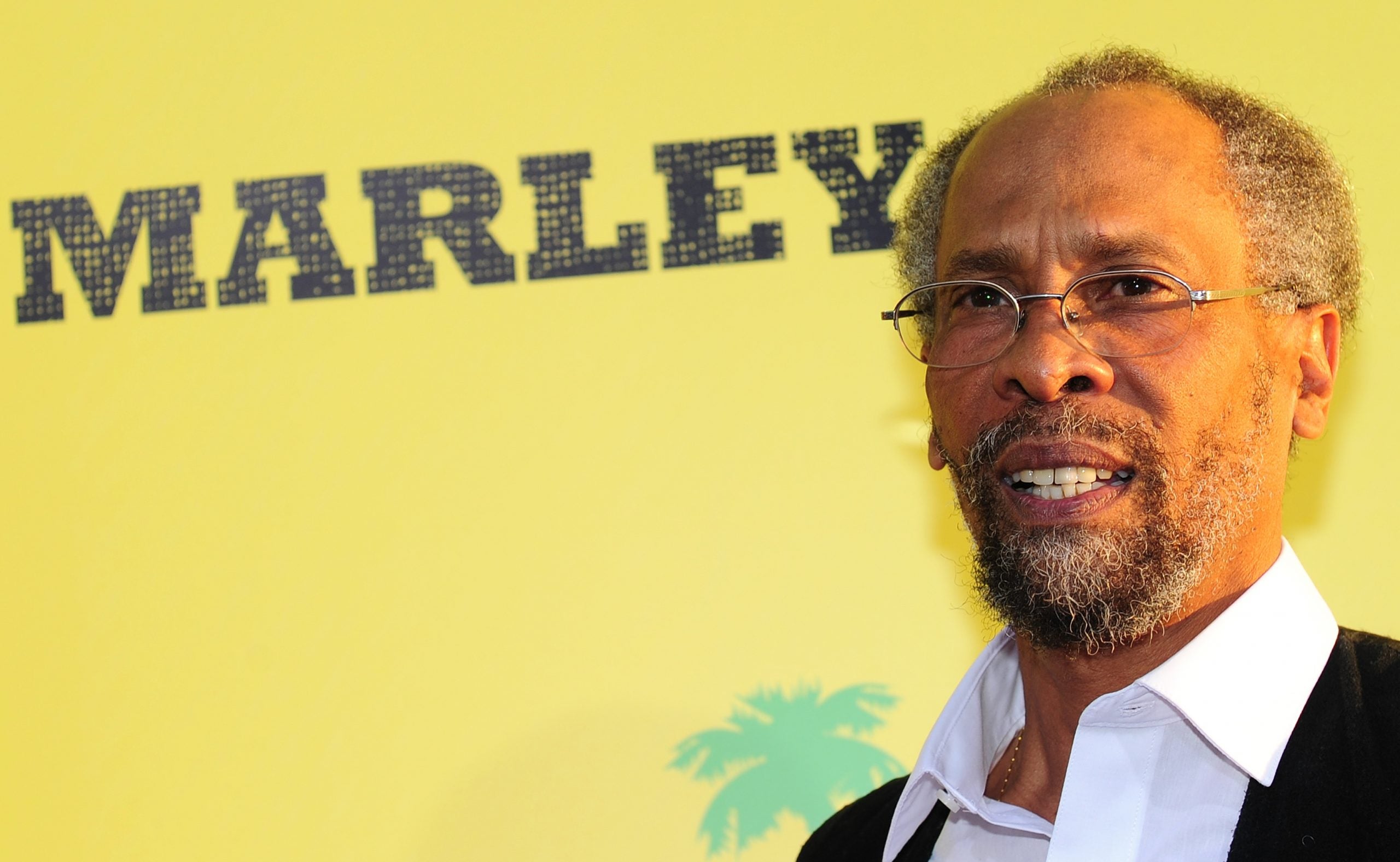

After the screening Marley’s longtime friend and art director Neville Garrick explained why Marley touched so many people. “Bob Marley is a man that came from humble beginnings,” he said. “Through the color of him skin he get persecuted—red bwoy, half cast all that—but that just make him stronger. Him say ‘I’m not on the white man side and I’m not on the black man side. I’m on God side.”

By overcoming great hardship in his life, Marley became a universal symbol of triumph over adversity. “I think he lift the spirit of people universally that you can make it if you try,” said Garrick, who chose Marley’s “Redemption Song” as the most important in his entire catalog. “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery,” Marley sang on the track. “None but ourselves can free our mind.”

“We are special. It’s our movie. It’s made here. It’s about us,” said Dr. Carolyn Cooper, professor Emeritus at the University of the West Indies and author of many books on reggae culture, who turned out in a dazzling African-inspired dress. “I think this film is really a wonderful way to affirm the cultural power of Jamaica to think that a little island can produce such great people and Bob Marley’s music in particular transcends time and space. Anywhere in the world you go and you say Jamaica, they say ‘Bob Marley.’ I think of ourselves as Island people with a continental consciousness,” she added. “We are not limited by this small island we know we come from a vast continent.”

Cindy Breakspeare, mother of Bob’s youngest child Damian Marley and former Miss World, described watching the film as an emotional rollercoaster. “Anything to do with Bob is always larger than life,” she said. “It is always unifying and the music is so powerful. I think that Kevin really captured the journey from the beginning right through to the end of his life.”

The final scenes of the film were particularly painful for Cindy, who was there by Bob’s side during his last days. “He was really suffering and his locks were gone,” she recalled. “I just go back to the night when we cut them and what that felt like, and going to Germany to visit him there, and finally coming to Miami the day before he passed with Damian to see him for the last time.”

“It was really really hard to see such a great human being losing their life,” she remembered. “I won’t know anybody like that in my life that again. The closest is my son and his music inspires me too, but I won’t be lucky enough, I don’t believe, to be that close to that kind of greatness again in my life. That doesn’t come along that often.”

Reshma B (@ReshmaB_RGAT) is a music journalist specializing in reggae and dancehall. She produced the film Studio 17; The Lost Reggae Tapes.