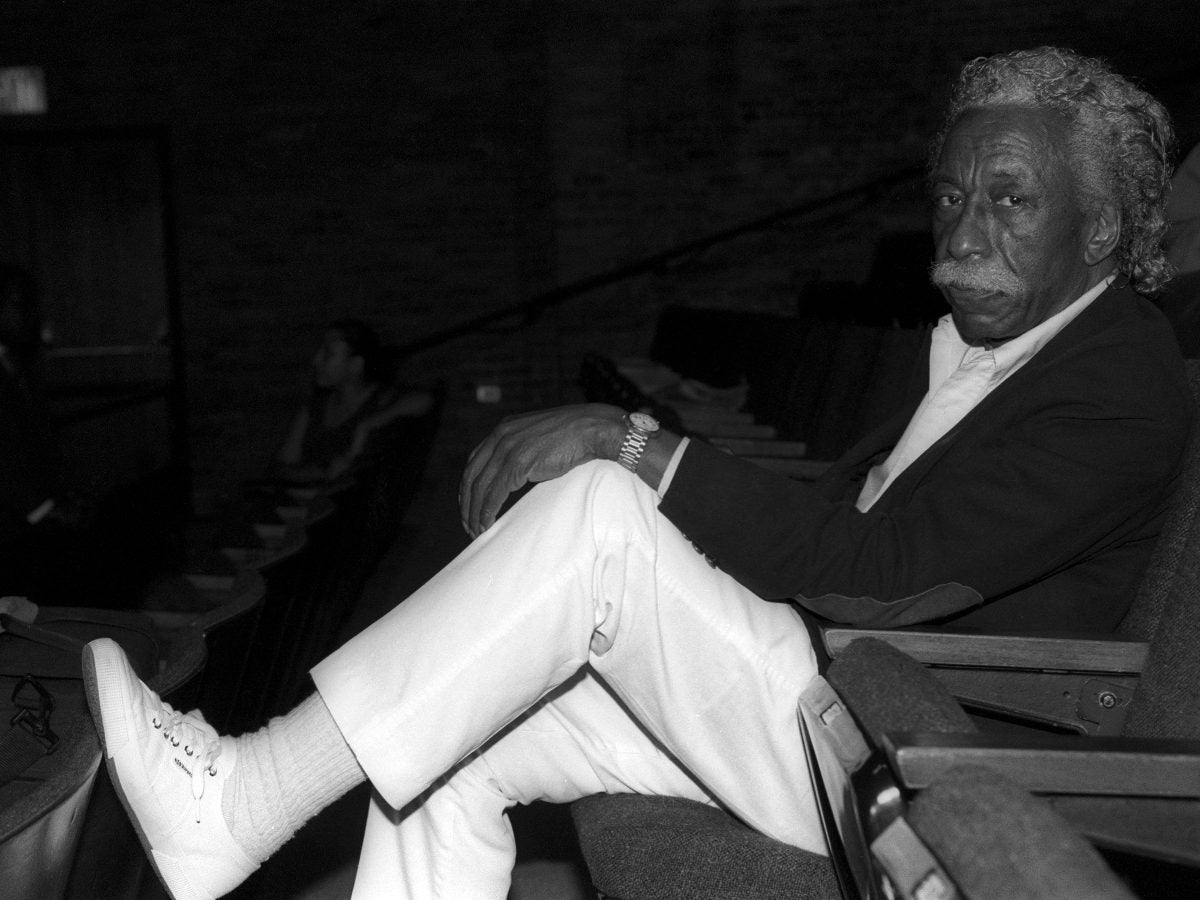

By the time Gordon Parks shot his first photograph for Life Magazine, his mother had died, racism had forced him out of his hometown of Fort Scott, Kansas, and he’d worked in brothels, as a singer, and as a professional basketball player. He was not yet 30 when he captured the infamous image titled “American Gothic” and the follow-up sequence of photos of Ella Watson. Watson worked as a cleaner in the Farm Security Administration building where Parks had a fellowship. HBO’s documentary, A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks, doesn’t simply examine the photographer’s extensive body of work. It also explores his activism and what it meant to preserve the 20th-century Black experience through his camera lens.

In all of his varied versions of life, Parks strived to be seen, and he learned quickly through his photographs how important it was for the world to see Black people as they truly lived and existed, instead of solely through a white gaze. By documenting the lives of Malcolm X, Black rural Southerners, and even a gang leader in Harlem, Parks would become a leader, inspiring a new generation of photographers who have used their cameras to active their voices.

Photojournalist Devin Allen had only begun to wield his lens when his “Baltimore Uprising” photograph was used as TIME Magazine’s cover photo in May 2015. LaToya Ruby Frazier’s examination of the Black working class inspired a deeper connection with her subjects. Documentary photographer Jamel Shabazz has been photographing people of color since the ’70s as a means of reflection and Black joy.

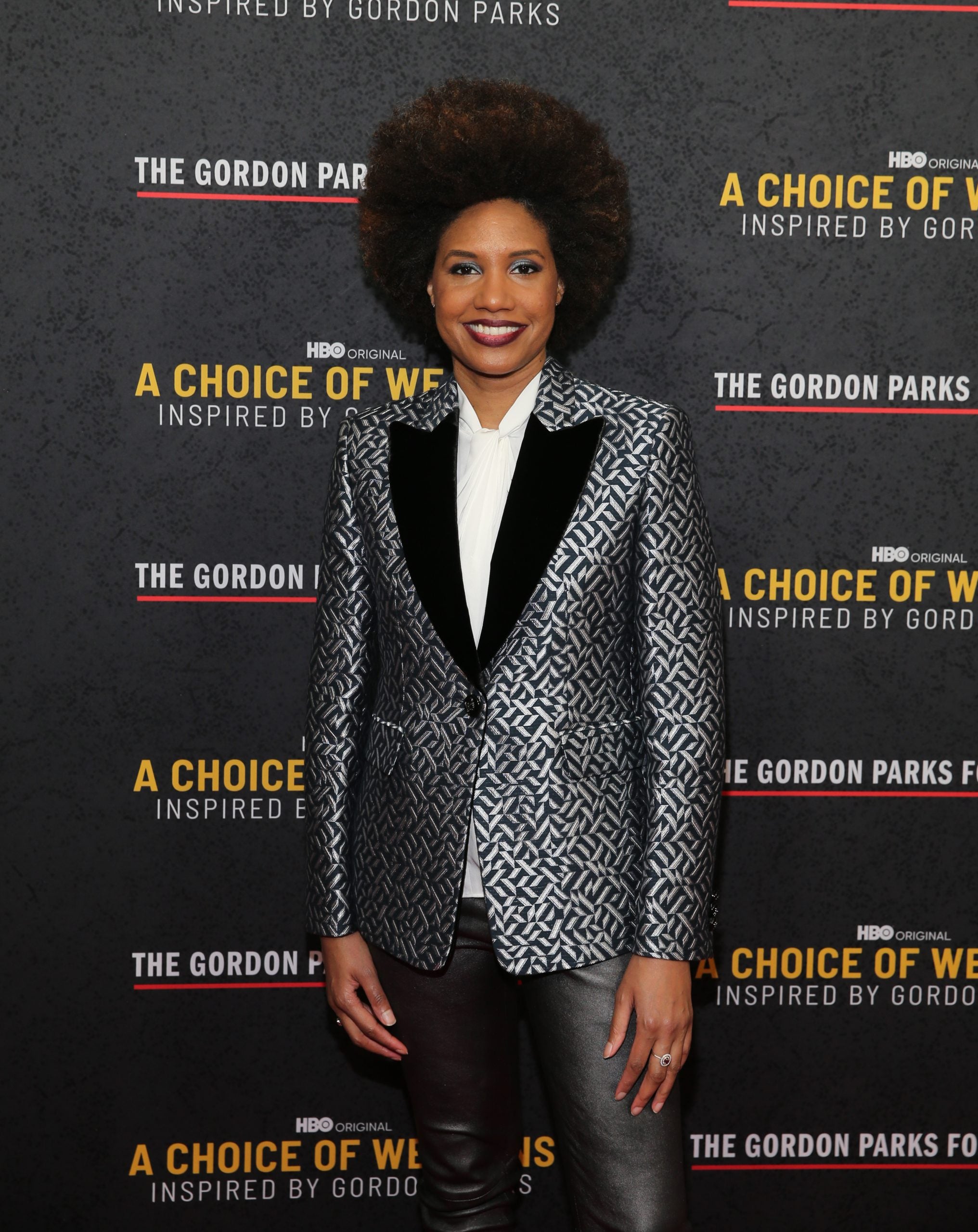

Frazier’s journey behind the camera came only after immersing herself with her subjects. “I was making portraits of families living in homeless shelters in Erie, Pennsylvania for my beginning photography course at Edinboro University,” she explained. “At first, I did not take my camera to the shelter but instead spent time with each family to the point people thought I resided in the shelter too. One evening, there was a lovely Black woman whose omnipresent energy had drawn me in close to her. When I returned the next week to give her prints of her portrait, that’s when she told me that the image reminded her of a man she once saw on PBS named Gordon Parks and then [she] asked me if I ever heard of him, to which I replied, ‘No,’ and she said, ‘Well you should.'”

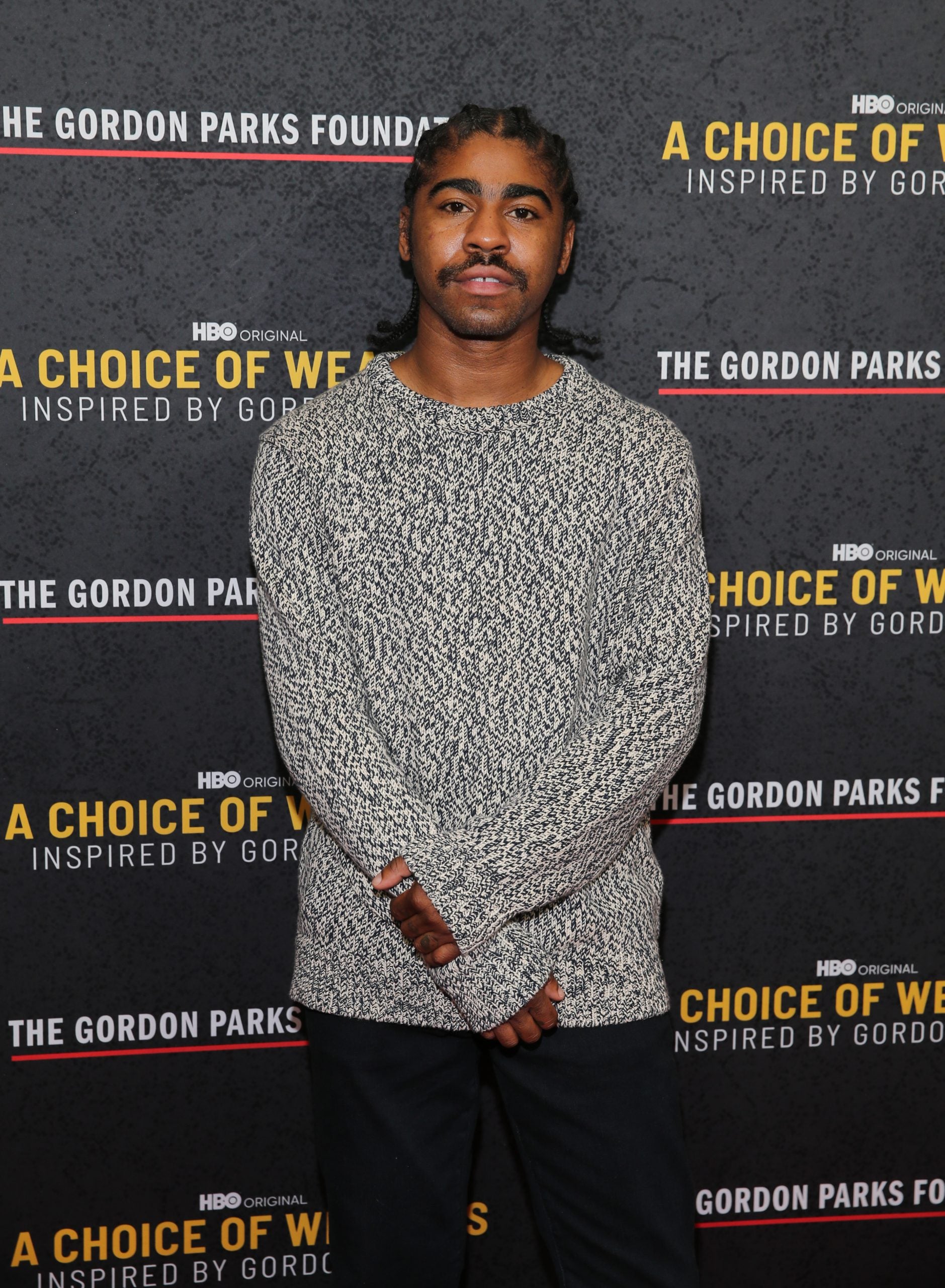

Allen’s introduction to photography came much more recently—almost by accident. “A lot of people who see my work think that I’ve been in the game for a long time,” he explained when looking over the trajectory of his career. “The first time I actually picked up a camera was maybe about 2012, and Instagram was coming out and getting popular, and pictures were becoming a thing. The closest thing I knew to a photographer was my grandmother taking pictures at the family reunion and cookouts and the picture man in the club with the photo booth. I didn’t know anything beyond that. When I Googled ‘Famous Black photographers,’ [Gordan Parks] was the person that popped up. And then after that, it just was like a rabbit hole of going through his life and his career.”

When Shabazz first picked up an Instamatic 110 camera in 1975, it gave him a new sense of direction and purpose. “It allowed me to utilize my third eye and see the world from a whole new perspective,” he explained. “The camera almost became a life accomplice to me, and it put me on a path. At that point, I was given an assignment, and I never stopped from that point on. I realized I had a responsibility, especially during that time when I grew up and we would constantly see negative images of ourselves. So when I aimed my camera at someone, I told them they were beautiful, they were special, that I recognized the beauty within them. It made a difference.”

Once Fraizer did discover Parks’ legacy, it has remained with her ever since. In fact, “American Gothic” resonates with her above all others. “It is not a coincidence that the central figure depicted, Ella Watson, is a Black woman that is an undervalued, underpaid, [and] invisible,” she said. “Parks’ conscious decision to use a visual play and subversionary tactic on Grant Wood’s iconic painting, American Gothic 1930 that portrays an elder white couple he respected, to me, asks viewers a question, ‘What is the value of a Black woman’s life in America?’”

Shabazz was aware of Parks’ work and legacy long before he learned the prolific photojournalist’s name. “I was always reading Life Magazine, and I vividly remember seeing photographs of Gordon Parks, but back then, you didn’t pay attention to the name; you just appreciate the images,” he remembered. “It wasn’t until I was in the military station in Germany that I started to understand better who Gordon Parks was. Not through his photographs, but through a book that his son David did on his experience in Vietnam called GI Diary.”

Parks’ images are one thing, but Allen has used the photographer/filmmaker’s career to blueprint his own work. “It wasn’t so much the imagery, it was him as a person and how he was able to navigate so many spaces,” the photographer explained. “Baltimore was a pretty segregated city, so I didn’t start interacting outside my community and start meeting white people and people outside of the Black community until I was almost 20-years old. As Black artists, we should reflect on what’s going on around us. I think it’s very, very important. I’ve felt voiceless for years. So it was already instilled in me that I needed to be on the front lines. I felt like nobody could tell this story better than me because I’m from West Baltimore, and I just knew that I needed to be there. We have to control the narrative of our own community.”

Parks was an activist not just because of the spaces he could enter but because he shared an authentic perspective of Black people with the world. Still, though she sees herself as an activist, Fraizer doesn’t think Black artists should be forced to wear that label. “I was born into an environmentally hazardous steel mill town in the 1980s,” she explained. “[I] was raised by my Grandma Ruby who supported and encouraged me to be an artist. It led me to the revelation that If I was going to survive then art and education was the answer. My camera is my compass and my guide.”

In contrast to Allen and Fraizer, much of Shabazz’s work consists of images of the past. They are stunning reflections of Black and brown people from the ’80s and ’90s. “What has happened since COVID, it has given me an opportunity now to go through my archives and scan thousands upon thousands of negatives,” he explained. “In looking at them on my computer screen, it amazes me to look at a frozen moment in time. I might have created an image over 40 years ago that I have absolutely no memory of — it brings me so much joy. But what I find even greater is having a platform like social media, Instagram in particular, and sharing that image and now have so many people reach out to me and say that they’re either in the photograph or it’s a loved one. That really warms my heart.”

For Allen, it’s never been more critical to have a real perspective in your work. “I just hope that everybody who is on the ground understands how important and vital the work that photographers are doing,” he said. “So for me, I believe the people who shoot with their heart, their intent is to make change on the ground for a reason. Those are the people that I gravitate to, and you can feel it sometimes in the imagery, that person cares about the image and what they digest and process and put into it.”

Though Parks’ work will permanently be embedded in American culture, Fraizer feels that it’s up to a new generation of photogs to continue the work he started. “There is a great need for a new movement of photographers in a post-COVID-19 American landscape as we come out of another economic recession that enables working-class Americans to tell this story and write this history ourselves, free of corporate propaganda,” she explained.

A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks debuts November 15 at 10 PM ET/PT on HBO.