My Auntie Rhoda’s CD collection was the business.

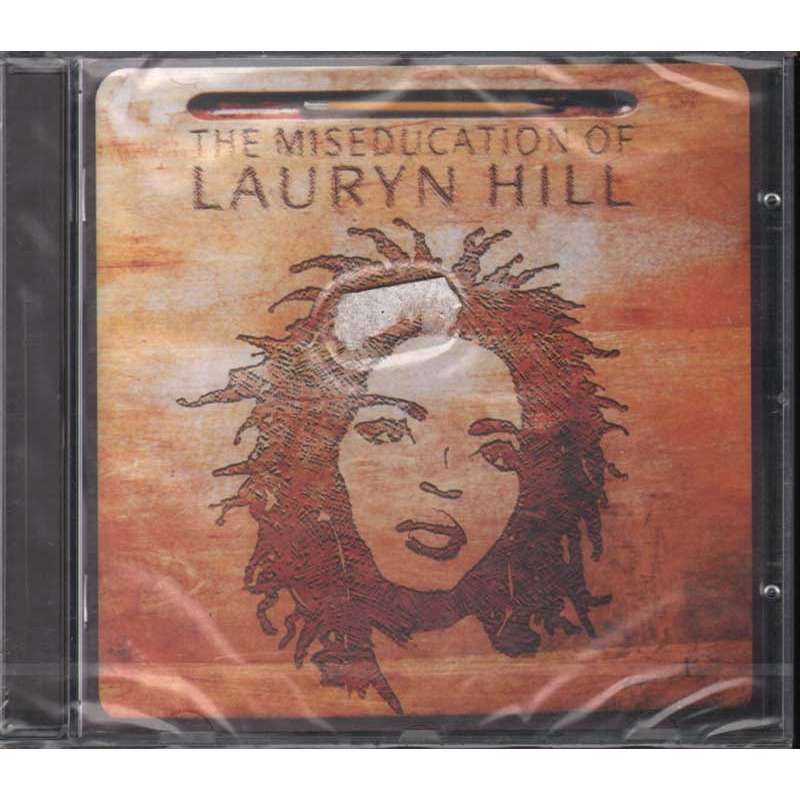

I mean, she had albums from Da Brat, India.Arie, Carl Thomas (and any other Black artist who was making waves in the 1990s) all in little slots. Excuse me while I reminisce over the days of instantly recognizable album art and the nervousness that came with accidentally breaking the plastic bits that held the CD case together.

Anyways, my aunt, like many other other Black women, bought Lauryn Hill’s debut project. I was a tot watching Hill walk tall above a city built on vinyl grooves in ‘Everything Is Everything.’ A teenaged John Legend sounded damn good thumping those piano keys. The record scratches were pronounced and my, how that drum kicked. But more than the technical sound, the song felt good. It was fresh. So began my conscious treasuring of The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.

Ten years later, my sonic taste had obviously been elaborated on. Yet, I was still very much interested in the gospel-meets-raw soul Hill presented and stood by. I had begun to respect her words, deeply. I grew up in a small, storefront-turned-church in the Deep South, so “Final Hour” was a rehashed lesson on material pursuit. “Superstar” asked me to reconcile with how popular rap had strayed from politically focused roots. “Ex-Factor” was a slow burner that spoke to relational complexity and decisions that aren’t difficult on paper, but emotionally so. The self-titled finishing cut was an early talk on destiny and manifestation, back when the latter didn’t have as much of a presence in the mainstream lexicon. The album was a honey-laced scolding, a relatable weaving of relationship talk and a boost of confidence all in one. As a Black woman coming into my adulthood in the time of instant communication and societal devaluation, I needed Miseducation. So I bought my own copy, that gained more than a few scratches, at a used record store.

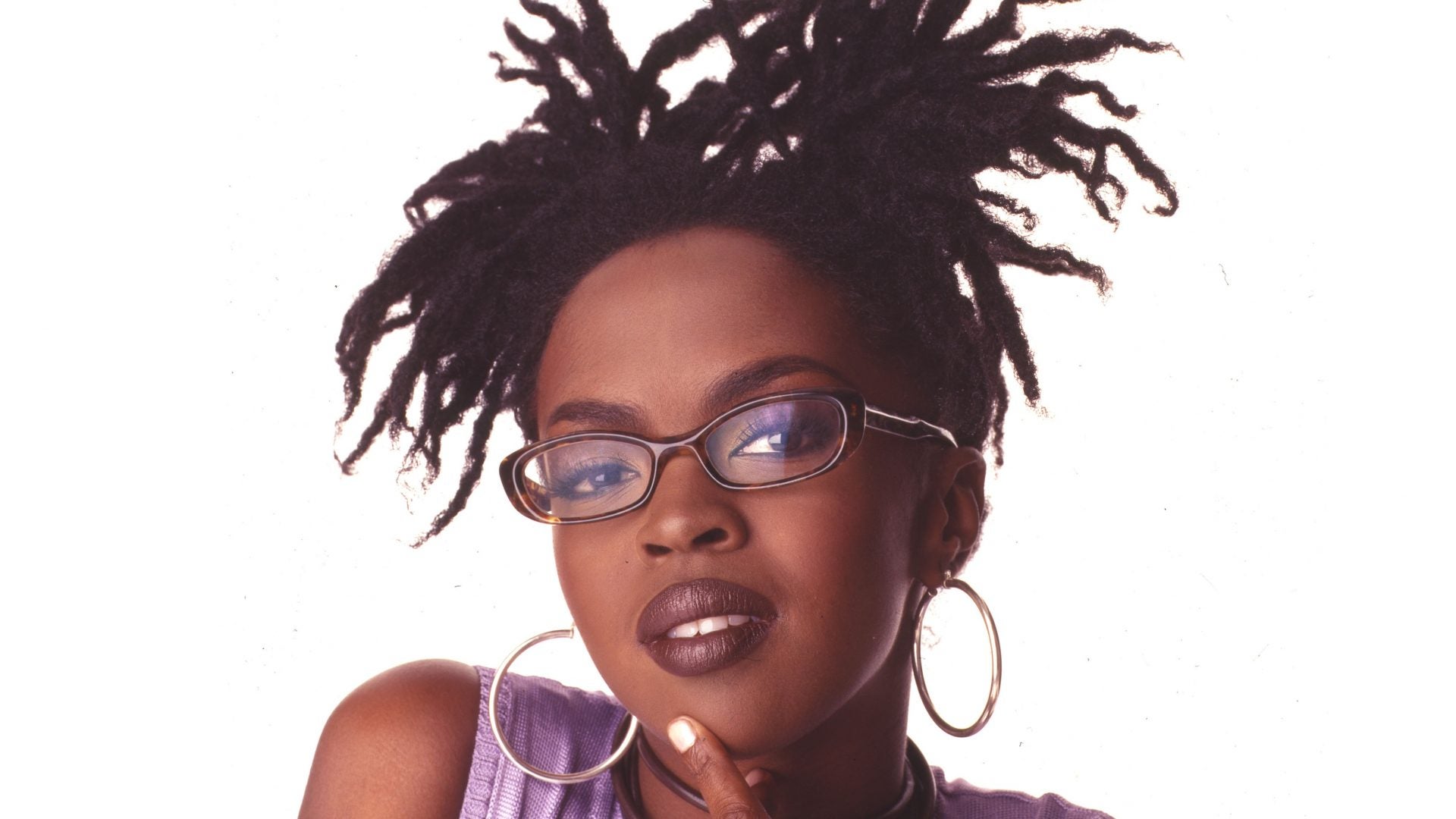

In 1998, the year Miseducation was released, the Black community was grieving. One of our heroes, Olympic track and field gold medalist, Florence Griffith-Joyner, had died suddenly in her sleep. White supremacists in Jasper, Texas brutally lynched James Byrd Jr. and left his body in front of a Black church. Beginning in the 1960s and culminating in the 1990s, the number of American people incarcerated had shifted from largely white to majority Black, due to racially charged legalities. There was no perfect balm for such devastation and gut wrenching loss, but there was a need for healing in the wake of it. Hill wanted to be that hope and a voice for the underserved.

“I make music that communicates issues that aren’t always on top of the agenda, for people who aren’t always spoken for,” Hill said in a 1999 interview with Rock’s Backpages. To me it’s not political, because there’s nothing partisan about what I do. I’m not a democrat or a republican, I’m just a musician who speaks for people who, no matter what they vote, still don’t have that much of a voice.” Hill was prioritizing our plights while blending our sounds (reggae, doo-wop, blues), to give us a body of work that would encourage our spirits and stand the test of time.

Awards aren’t always markers of excellence. Like, we know this. In some cases, artists even argue that their bestowment is rather a result of a secret society of tastemakers. It’s special when you mold art that can speak to the very soul of the Black masses, while also getting plaques and stacking paper. As of 2021, the 4-time Grammy-winning album is certified diamond. It did not sacrifice its majesty for a trophy and for over 20 years, we have been those loud family members in the audience of a graduation. She did it. The administrators ask us to hold our applause until the end but we refuse. Our sister has been re-educated and accoladed. We are too proud.

My aunt has traded in her CD collection for a smart phone, storing her favorite jams that way. As have I. We’re exactly 20 years apart, separated by common generational experiences, mainly the introduction of social media as a staple. We’re more alike than either of us can properly explain though. She knows a hot beat (“Lost Ones”) when she hears one, I can dip my fingers into lyrics and find every drop of love (“Tell Him”).

“I wanted to make an album about love, something joyful, something sincere. I wanted this generation to know something, I wanted us to talk about love,” Hill said to a live audience in 2018. So that’s Lauryn’s gift to us as Black folks—-the mothers and fathers, sistas and brothas, aunties and nieces—love. The connective tissue of our community, the intangible magic, and at the end of the day, all that there truly is.