How much do you know about the Black history of space exploration? It was something never taught in schools growing up, and I still didn’t know much about it now. But a new documentary from the Smithsonian Channel is hoping to change that.

From Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Laurens Grant, Black in Space: Breaking the Color Barrier takes a look at America’s race to space and the Black astronauts who made history against the backdrop of the Civil Rights Movement. The documentary features Ed Dwight, the first Black astronaut trainee, Carl McNair, brother of late astronaut Ronal McNair, and Fred Gregory, the first Black person to command a space flight.

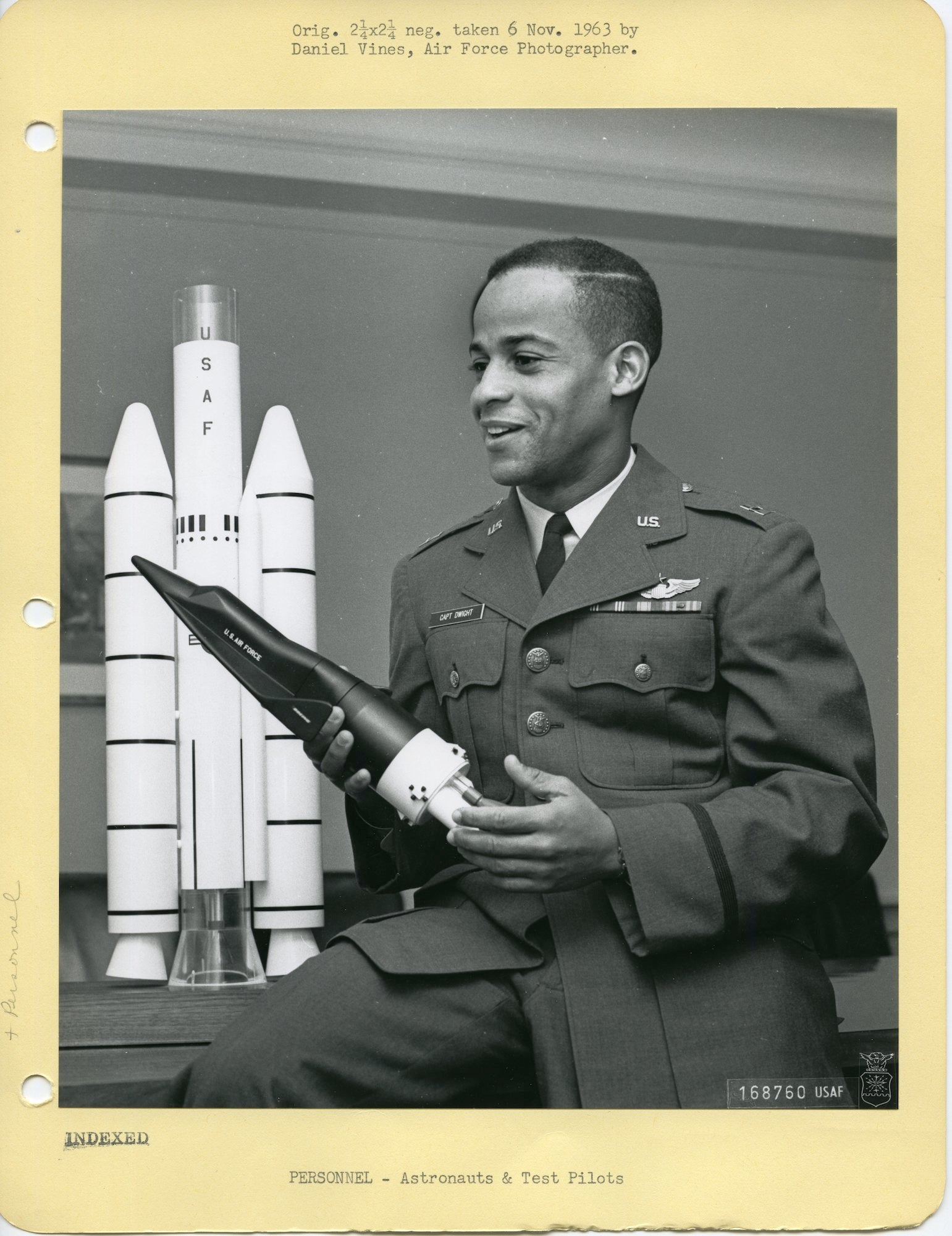

The documentary begins with Dwight, an Air Force captain chosen to train as an astronaut following calls from Black Americans and President John F. Kennedy. Picked to train during the Civil Rights Movement, NASA’s race to space wasn’t just about beating the competition technologically, Kennedy’s administration wanted to send the first Black man to space. However, Dwight faced push back from members of NASA and the film suggests that Air Force pilot Chuck Yeager reportedly lobbied against Dwight because of his race.

“The whole space program was really about how far can you stretch a man before he breaks,” Dwight told ESSENCE. “How much can he take? Whether it’s doing spacewalks, how long can you last? What is your endurance? All those things. That came with the territory and the fact that you survived it, to walk away and say, ‘I did that,’ it’s incredible. I did it and I did it well.”

However, NASA’s politics eventually pushed Dwight out of the organization, with Black in Space pointing to Yeager’s possible interference and leaked reports that Dwight could not keep up with the rigorous program. He denies that he struggled with astronaut training.

“When we think about what NASA did to make the first seven astronauts [known as the Mercury Seven] heroes, they spent millions of dollars telling the public they found seven heroes out of 30 million people; that they got seven guys who were supermen, who could go into space to fulfill our dreams. They were special men. They had special bodies, special brains, and all that stuff. The idea of a woman or a Black person, equally doing it, that was just preposterous. You couldn’t. Don’t even think about comparing those two things.”

Dwight also watched as the USSR used propaganda to compete with NASA, claiming that their space program was much more diverse. Soviets saw the opportunity to send a Black man to space as a way to say that they were superior to American’s who believed that the American dream was available to all. In 1978, Afro-Cuban Arnaldo Tamayo Méndez joined the Soviet Union’s Intercosmos program and became the first Black man launched into space.

We’ve come from slave ship to spaceship, and we will continue to rise into endeavors far beyond that.

Carl McNair, the brother of Ronald McNair, the second Black astronaut to space travel

“I knew it could be done,” Dwight said, sharing how he felt about the news of Méndez’s trip to space. “And I knew if Kennedy hadn’t died, that would have been me. He was my sponsor. He put me in the program and he got me through all the stuff that I was going through.”

Dwight added that, at the time, there were tons of political conversations going on that he later discovered, including how the Soviets and Americans rushed to secure Nazi scientists and German equipment after World War II in order to boost their own space programs.

“I had no idea all this stuff was going on. It surprised me. I didn’t know until I saw Black in Space that all that stuff was going on with the Soviets. I did not know that when I was here in the program.”

Dwight has since become a renowned sculptor, creating thousands of gallery pieces and 129 memorial sculptures.

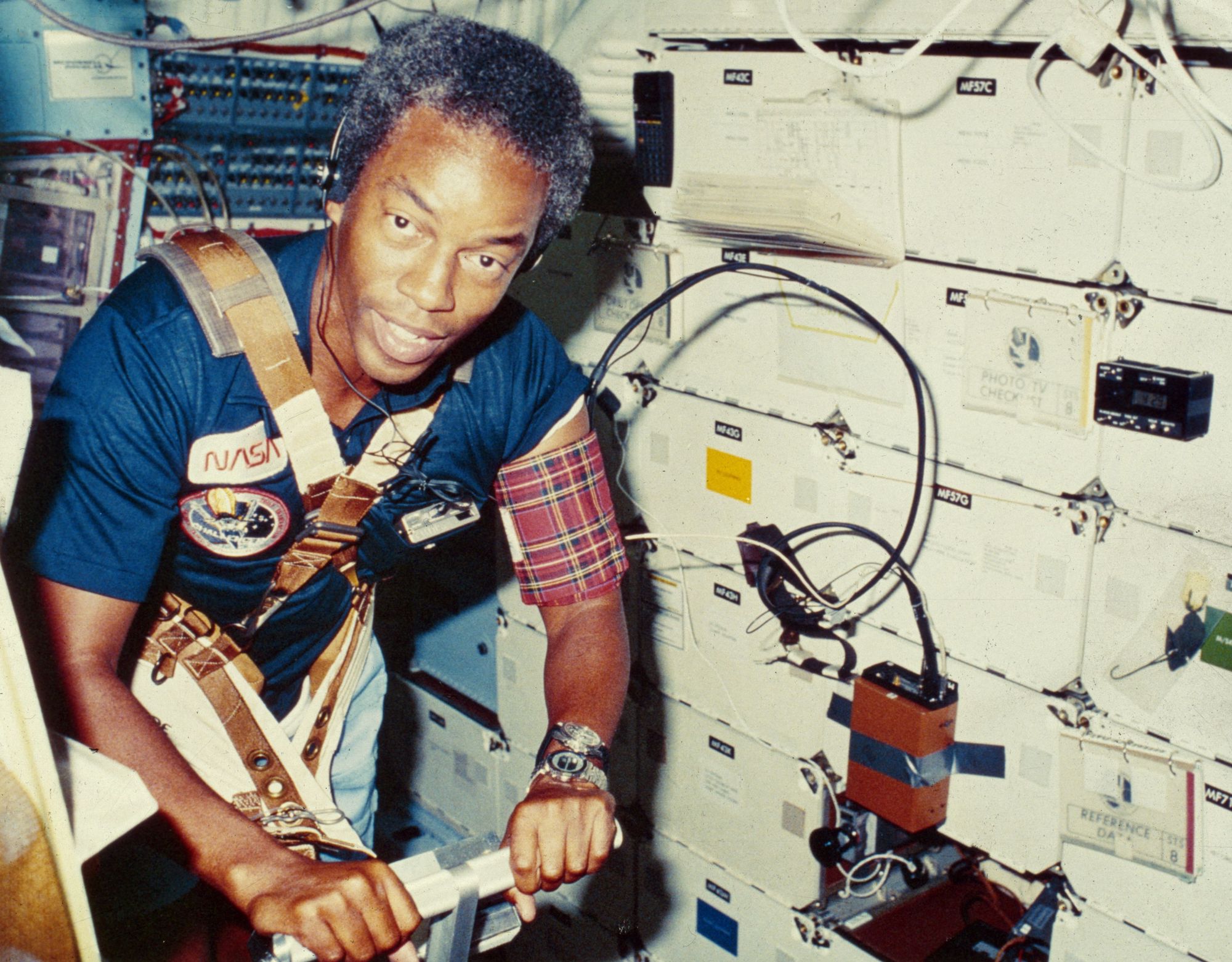

Eventually, America did send a Black man to space. In 1983, astronaut Guion Bluford Jr. became the first Black person to travel to space. This would open the door for other firsts too, such as Fred Gregory becoming the first Black man to command a space flight. Gregory said he only became aware of the historical moment when newspapers mentioned it.

“I never ever thought of anything like that,” he told ESSENCE, sharing that his motivation to become an astronaut came from those he knew. “I grew up in a family of educators. One of my dad’s attributes was that he never told me ‘no.’ He also had a lot of friends, pilots, and I would listen to them talk about their exploits and combat experience. I had these influences who kind of set an example to me about what it is to fly in space. I was just looking for something to do and I just saw an advertisement in a magazine that offered this opportunity. If I applied, I could become an astronaut.”

Gregory noted that that training with McNair, Robert Lawrence, the country’s first Black astronaut, and Michael Anderson, a Black astronaut that unfortunately perished in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster in 2003, was further motivation, “They were part of the future. They were looking at things in the future that would encourage young kids to look further forward.”

While the Black history of NASA includes many firsts, it also includes tragedy. Ronald McNair became the second Black person to travel to space after being selected as one of 35 applicants out of a pool of thousands to join NASA’s astronaut program. On January 28, 1986, McNair died during the launch of the Space Shuttle Challenger.

“He was a country boy,” McNair’s brother Carl shared with ESSENCE. “We grew up in Lake City, South Carolina. The population at the time was less than 2,000. Most of the folks in that town were domestics. If you were going to be a white-collar professional, you either had to be a preacher or teacher. This was during segregation. But we were both inspired to go to North Carolina A&T after meeting a [member of the] Air Force ROTC.”

Carl described Ronald as someone who “always called it like it is” and who was “always a bit of a risk-taker.” He added, “He was one of those natural leaders. Kids in the neighborhood, if Ronald said it, they considered it gospel.”

Ronald would also challenge teachers and authority by “always asking for more; more challenging problems in math; more challenging problems in physics and that kind of thing,” Carl remembered.

It was Ronald’s thirst for more that led him to NASA. His brother recalled being in graduate school at Babson College, when he found out his brother had been accepted into the astronaut program. “He called and said to me, ‘I don’t know if I should tell you this, but I’m going to be an astronaut.’ I thought, ‘Okay. This brother must’ve gone out last night, let me just play along.’ But one day [CBS Evening News anchorman] Walter Cronkite comes on television, I’m at home between classes and he says, ‘In from NASA, the first 35 space shuttle astronauts.’”

Carl tuned in, thinking his brother would be heartbroken at hearing he hadn’t made it into the program. It was a shock to him when Cronkite announced Ronald’s name. “I call Ron. Ron answered the phone. I say, ‘Congratulations man, you did it!’ He said, ‘Did what?’ I said, ‘You’re an astronaut.’ He said, ‘I am? I’ll call you back.’ Click.” Cronkite had broken the news before Ronald himself had even found out.

During his time at NASA, Ronald continued to inspire others. An accomplished saxophonist, he’d hoped to become the first person to record an original piece of music in space. His brother now shares his legacy with the world through the McNair’s Scholars Program, speaking engagements, and a book, In the Spirit of Ronald E. McNair Astronaut: An American Hero. Carl hopes that Black in Space inspires others from minority groups to pursue STEM, to look to astronauts like his brother or Mae Jemison, the first Black woman to travel to space, as examples of what’s possible.

“I once mentioned that Ron was planning, after that last flight, to leave the space program. He had already assumed a professorship at the University of South Carolina, where he would be a professor of physics,” Carl said. “He wanted to use his story, his accomplishments, to encourage other young people, African-Americans in particular, that if this country boy coming from where he came from could do it, you can do it too.”

“I want [viewers] to take away the fact that there were others during even harsher times than we’re going through right now, and in spite of that, they have succeeded and we will continue to succeed too. In spite of the political situation as it is right now, in spite of all the continuous roadblocks that have been drawn in front of us, we’ve seen this movie before,” he added. “We have been here, we’ve done that. We’ve come from slave ship to spaceship, and we will continue to rise into endeavors far beyond that.”

Black in Space: Breaking the Color Barrier airs tonight at 8 p.m. ET on the Smithsonian Channel.