We were too young to understand the yearning in Angela Bofill’s voice on “I Try.” All we did then was laugh all day and play music. But we’d rewind that song of unrequited love and play it again and again. It was one of the many songs I taped from The Quiet Storm to create slow jam playlists with just a finger and a pause button.

Scott Jarrett’s “The Image of You” would start the evening on WKYS-FM 93.9 in Washington, D.C., where I grew up. Then a soothing alto voice would slide onto the radio airwaves: I’m your host for this evening. My name is Melvin Lindsey.

In the 1980s and 1990s on WKYS, Lindsey would play songs by artists like Sarah Vaughn, Luther Vandross, Diana Ross, Phyllis Hyman or Patti LaBelle, any one of his favorites. It all depended on his mood. His song selections from his personal record collection told the story of how he was feeling each evening—whether he was heartbroken or in the early obsessive days of a love affair.

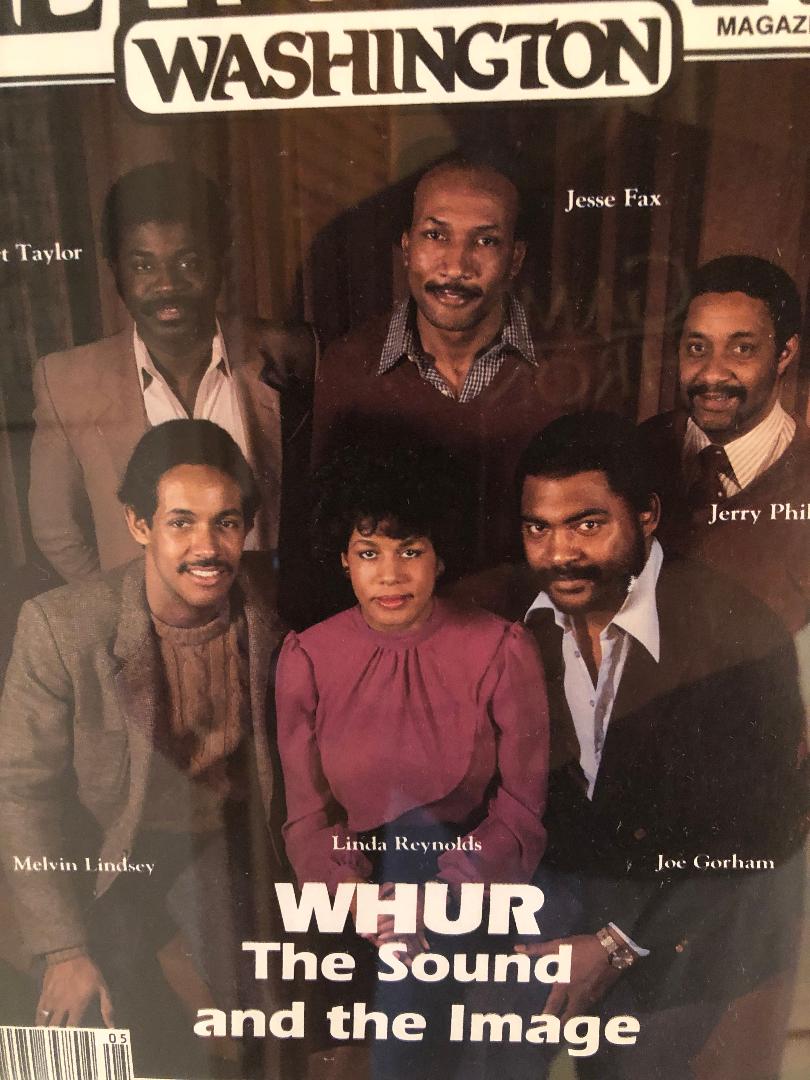

The Quiet Storm show had begun in 1976, when Lindsey hosted on WHUR-FM at Howard University and ultimately became the most popular evening program in the District. For media magnate Cathy Hughes, then WHUR’s station manager, she had created the show’s format—even suggesting the use of the Smokey Robinson song as its title—and the station rose from 20 in ratings to number 3, boosting revenues for the station. They were both on top of the world. Then Lindsey quit.

This is the story of how two scrappy young people tapped into talents they didn’t know they had and created a Black music genre that’s a forever mood. But let me take you back to the beginning.

* * *

In 1976, twenty-one-year old Melvin Lindsey had just graduated cum laude with a journalism degree from Howard University and had just begun hosting The Quiet Storm part-time at WHUR. Every time he did, the phones would light up non-stop. And then things changed.

Hughes, then Cathy Liggins, was livid about his move to their competitor station. Lindsey was a reluctant convert to broadcasting and Hughes was the reason he was even on the air at all.

“Melvin walked into my office on a Friday and told me that he had been offered this opportunity at WKYS,” Hughes remembers during a recent phone interview. “I’m thinking he’s gonna have me negotiating for him. He said, ‘I just want you to know, this will be my last day here…’ I went ballistic. I said, get out of my face.”

Lindsey hadn’t given Hughes the customary two-week resignation. When he went to WKYS he ended up in the mailroom, rather than the promotions department and quickly came back to WHUR a few months later, Hughes recalls.

The Quiet Storm eventually became a 5-hour nightly show with Lindsey as the host in 1977. Within a year of his hosting, The Quiet Storm was number 1 in its time slot.

For nearly a decade at WHUR, Lindsey spent his nights spinning records for his mostly female audience, telling stories with his music and blending eclectic mixes like Roberta Flack’s “First Time Ever I Saw Your Face into Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are.” From his playlists babies were made, fights were forgotten and women offered marriage proposals to Lindsey.

He would eventually become one of the highest-paid Black radio talents in the country.

In 1985, when he decided to move to WKYS again, this time it was for a million-dollar contract at age 30. Then popular WKYS deejay Donnie Simpson told a Washington Post reporter, “Melvin’s coming increases our chances of being number one again.”

Hughes and Lindsey didn’t speak for a couple of years as Lindsey continued making an impact on radio, buoying a new FM format, breaking new artists and having radio deejays copy his format and style.

During that time Hughes wasn’t doing so bad herself. She sextupled advertising revenue at WHUR within a year of being the sales manager and she began amassing her media empire, which would ultimately become Urban One. Back then, she started buying up troubled radio stations like it was chocolate candy and transforming them, starting with the first Black talk radio station WOL-AM in 1980 and eventually even her old competitor, WKYS, in the late 1990s.

Hughes used her radio platform for activism in the tradition of Black radio, paying rent for shelters for children, protesting utility shut off practices and raising hell on issues of race. She sparked a three-month protest of the Washington Post‘s magazine because of racist imaging and stories. She provided a voice for the voiceless and gave D.C.’s homegrown music, go-go their first play when other stations wouldn’t play the music.

Meanwhile, Lindsey remained loyal to what he and Hughes created at WHUR. In 1985, on the last night he hosted The Quiet Storm for the station, he told a reporter: “I think I must have cried a thousand times before that night.”

When he joined WKYS, he didn’t call the show The Quiet Storm, although hundreds of other hosts around the nation stole the name. The new name for his show was “Melvin’s Melodies,” taken from a segment he’d created on WHUR to spotlight his picks for the evening.

Cathy Hughes came up with the theme song for the show, Smokey Robinson’s 1975 whirlwind love ballad, “The Quiet Storm.” It was an obvious fit.

He and Hughes would pick up where they left off at a dinner honoring Lindsey, where he told his former boss and friend he was sorry about getting caught up with all the bullsh–t.

On his final show at WHUR, Lindsey signed off with the song “Best Thing That Ever Happened to Me” by Gladys Knight, a sentiment to how grateful he felt for his time at WHUR and a nod to Hughes for making it happen.

* * *

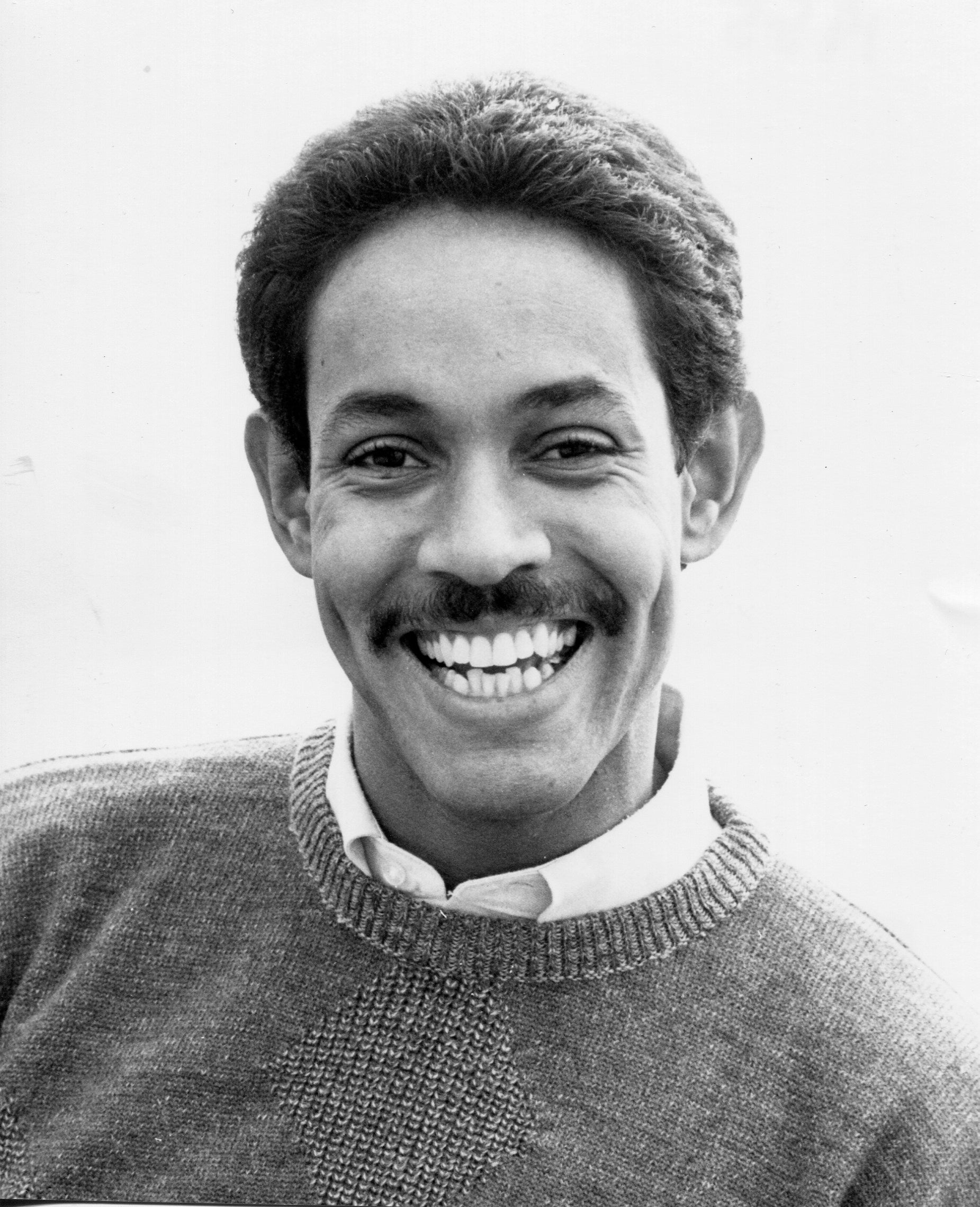

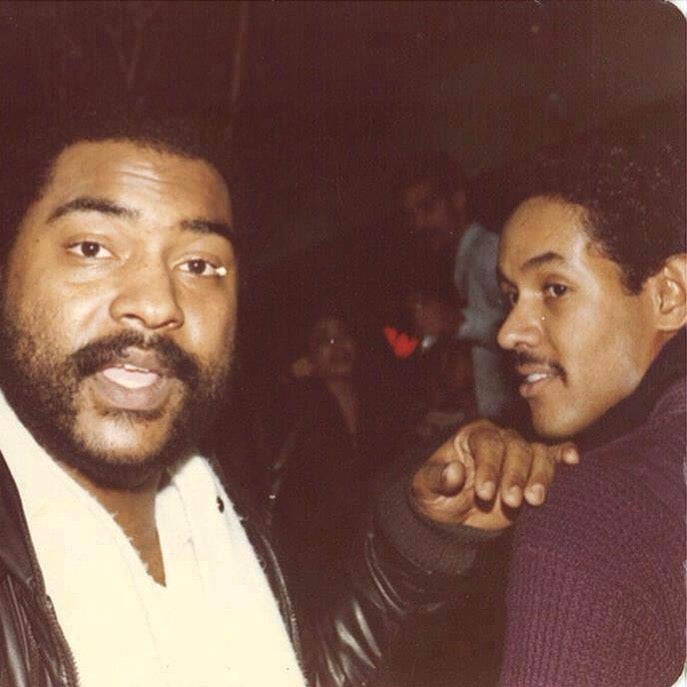

In 1975, Melvin Lindsey wore his hair long. Chubby and painfully shy, he wore coveralls nearly every day as a first-year student at Howard University. “He was like a little butter ball hanging around the music lab every day,” photographer Oggi Ogburn remembers.

“He was a generational native Washingtonian, but he looked like a farmer to me, so I called him my student from Nebraska. He found that hilarious,” recalls Hughes, who was a lecturer at Howard University’s brand new School of Communications and the intake counselor for freshmen.

Despite his country bumpkin sartorial choices, it was easy to see with his jet black, glorious curls, his gracious, gentle manner and his fine features that he would grow into a man that would have no problem with women.

Hughes met Lindsey when he was still a senior in high school. She was impressed with him off the bat. He trusted her immediately and confided in her that he wasn’t sure how his parents were going to pay for college as he was the youngest of six children.

Hughes hired him as her assistant after classes started his freshman year. She gave him money from her own meager salary. At 24, she wasn’t much older than the students she lectured and mentored and she had a 7-year-old son to boot. Lindsey would become like a big brother to her son, Alfred.

“He was a great assistant to me personally,” says Hughes. “He would pick up my son from school. I cooked dinner for the week on the weekends. Every morning I would bring my son’s dinner to the station. Melvin would come to the office from school, he would do his homework and then we would all sit down and have dinner at the station.”

There were other hosts of The Quiet Storm before Lindsey, Hughes says. There was Don Roberts, a senior who was a television major. He was so sharp, he got pulled away to a full-time job on television. When a deejay was absent, Melvin’s best friend Jack Shuler lasted all of one minute, visibly trembling and feeling nauseous about the thought of going on air. Hughes worked hard at talking Lindsey into trying it. They spent hours going through her record collection and Lindsey’s collection. And then there was the first time she got him on-air as a fill-in.

“He was worse than Jack,” Hughes says. “He was going into hysterics. I was shaking him and I wasn’t getting anywhere, he was a big kid, so, pow… I slapped him. He was like, ‘Thank you, I was tripping.’ I said, if you don’t want to do it, let me know. He said, ‘No, no, I’m fine now.’”

The switchboard lit up that May 1976 night when the audience heard the silky-voiced young man of few words. Lindsey made an immediate impact around the city with just a simple sign-on and sign-off and a streamline of non-stop love ballads that told a story.

There’s the urban legend that the night that Lindsey first went on the air there was a raging storm in the District. Hughes authorizes this telling of the story and adds, the storm, in addition to Lindsey’s quiet, but commanding personality, earned him and the show the nickname the Quiet Storm—a name she came up with for him.

“Melvin introduced jazz artists to the Quiet Storm,” says Joe Gorham, the deejay that followed Lindsey on the overnight shift. “Ramsey Lewis, Rodney Franklin, Roland Kirk. He broke a lot of artists by having the autonomy to pick his own music. Phyllis Hyman, The Jones Girls, Jean Carne. He was the first to play Scott Jarrett. He introduced D.C. artists,” says Gorham. “He played ‘Can’t Let Go’ [from D.C artist Parris] to death.”

Lindsey had his own record collection with artists like Carmen McRae and Les McCann who he played from and WHUR had one of the most eclectic, extensive libraries of music than any other Black radio station in the country that he pulled from.

“Other Black stations would call and ask if we had this or that record and we would send it to them,” Gorham says.

Hughes came up with the theme song for the show, Smokey Robinson’s 1975 whirlwind love ballad, “The Quiet Storm.” It was an obvious fit. (Lindsey initially wanted to call the show Mister Magic, in homage to the Grover Washington’s 1975 album of the same title.) Lindsey hosted the show part-time on the weekends.

“Over several months and years, he perfected it into an art form,” says Hughes. “I told him he reminded me of a very beautifully crafted ballet.”

Hughes had taken a course called psychographic programming at the University of Chicago, courtesy of Howard University—a course that brought up an idea for her about a Black muzak format—all love ballads. She knew it was something that could work for the D.C. night-time market. She even suggested to Howard’s president that it could be something that played all day in the elevators of Howard’s hospital.

But no one had listened to her. At least not that time.

* * *

Hughes didn’t just become a spitfire overnight. It was a trait that ran long in her family.

As a young girl, she’d visit her father in Chicago from Omaha, Nebraska, after her parents split. There were three Black people that lived in the apartment building where her father lived, John Ali, the CAO of the Nation of Islam, musician Ahmad Jamal and her father William Alfred Woods. Her father was the CPA for the Honorable Elijah Muhammad and Hughes helped her father during the summer and holidays. There was a bench outside his office where Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan often sat, because they were the two people that came to see Muhammad most often.

“I would walk past them [Malcolm X and Louis Farrakhan] and they would mess with me,” Hughes says. “Everybody in the Nation was like I should become a Muslim. A nice girl like me, ‘why didn’t I embrace Allah?’ I would run past them and stick out my tongue.”

On Hughes’ mother’s side, her grandfather Laurence Jones founded Piney Woods, one of the first Black boarding schools in the country that’s still in operation.

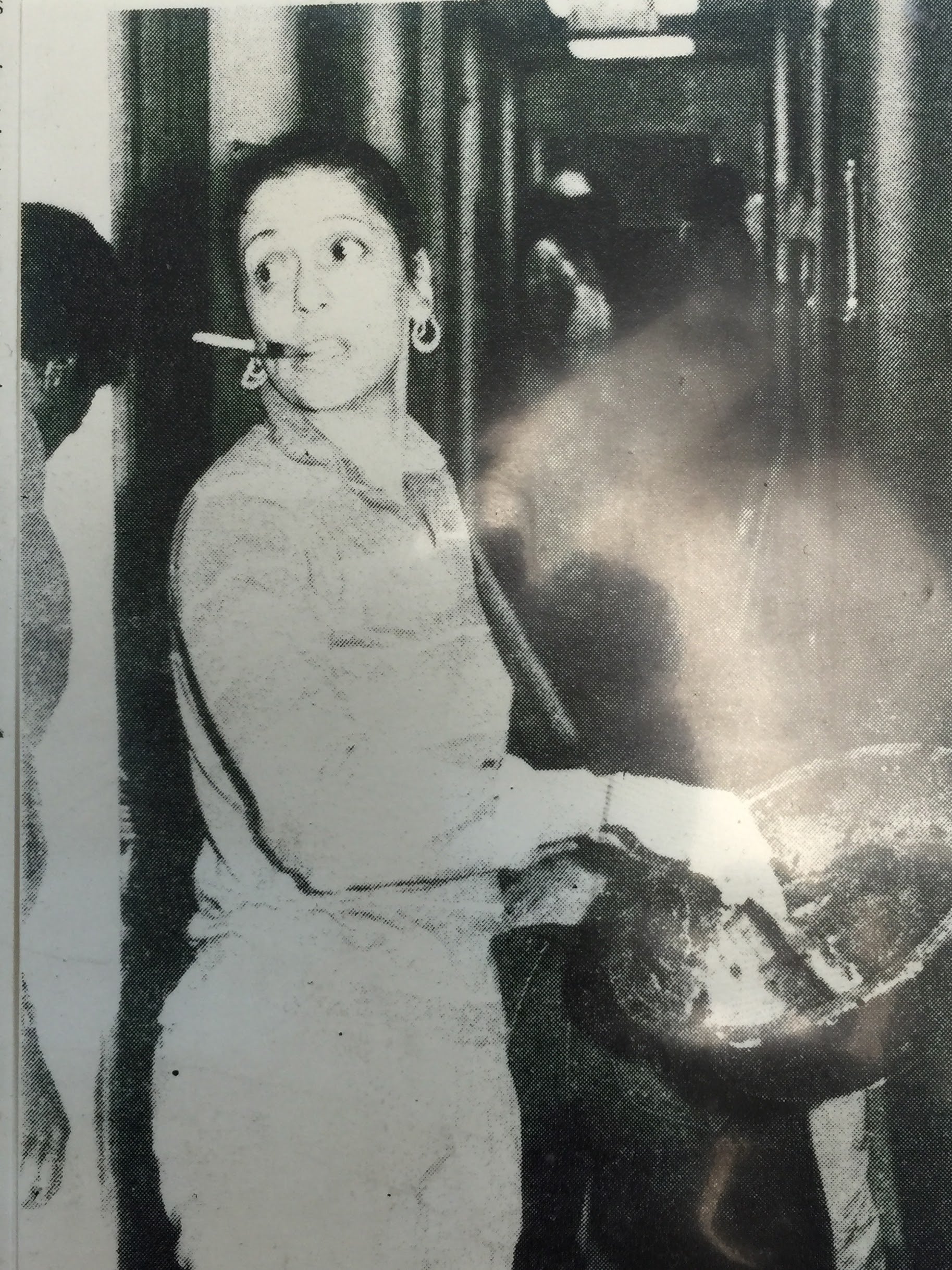

Hughes’ mother Helen Jones, was a trombonist for the International Sweethearts of Women, the first all-women’s band in the nation. She traveled on the road with Duke Ellington and Count Basie and played at venues like the Apollo and Howard Theaters.

Hughes’ great-great grandmother worked on the Underground Railroad with Harriet Tubman and took all eleven of her children with her. Frederick Douglass visited her great-great grandmother often and Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote her letters thanking her for her involvement in the women’s suffrage movement.

“She got to Iowa with 11 children, became a conductor on the Underground Railroad and was able to build a house in Iowa as an Underground Railroad station,” says Hughes, who found out some of her history recently through a project ancestry.com is conducting on her family.

Says Hughes, “All my life I wondered why I was a hell-raiser and now I know it’s in my DNA.”

* * *

Deejays Frankie Crocker and Vaughn Harper at WBLS in New York had been listening to D.C. radio. Howard University nor Lindsey ever registered Quiet Storm as a radio trade name. Harper co-opted The Quiet Storm format, along with hundreds of other deejays around the country. In San Francisco, one station, 102.9 KBLX, even played love ballads on a 24-hour rotation. After it took off in D.C. with Lindsey at the helm, it would be duplicated in nearly every major FM major radio market in the country.

But D.C. hosted the Quiet Storm as much as its original host Melvin Lindsey made a name for D.C.

A psychologist told me that The Quiet Storm brought peace in Black households. I started crying. I never thought of it like that.

Cathy Hughes

In the 1970 and 80s, Washington, D.C. wasn’t just the nation’s capital, it was one of the leading majority Black cultural capitals. WHUR was on Howard’s campus, the anchor of Black activism, intelligentsia and culture. Jazz clubs and supper clubs lined Georgia Avenue. There was a Black working class that earned good money, invested well and bought property and a growing Black middle class, brought on by incentives for Black-owned businesses created by Mayor Marion Barry and government jobs populated by Black people.

The city became a refuge for Black people migrating from the South. “There were Black doctors, Black dentists, you could go days without seeing a White person,” remembers Dyana Williams, who deejayed at WHUR at the time.

“There was a solid community of folks doing things, going places” remembers Amy Goldson, Lindsey’s attorney at the time. “It was the Chocolate City. Everyone looked so good, dressed so well.”

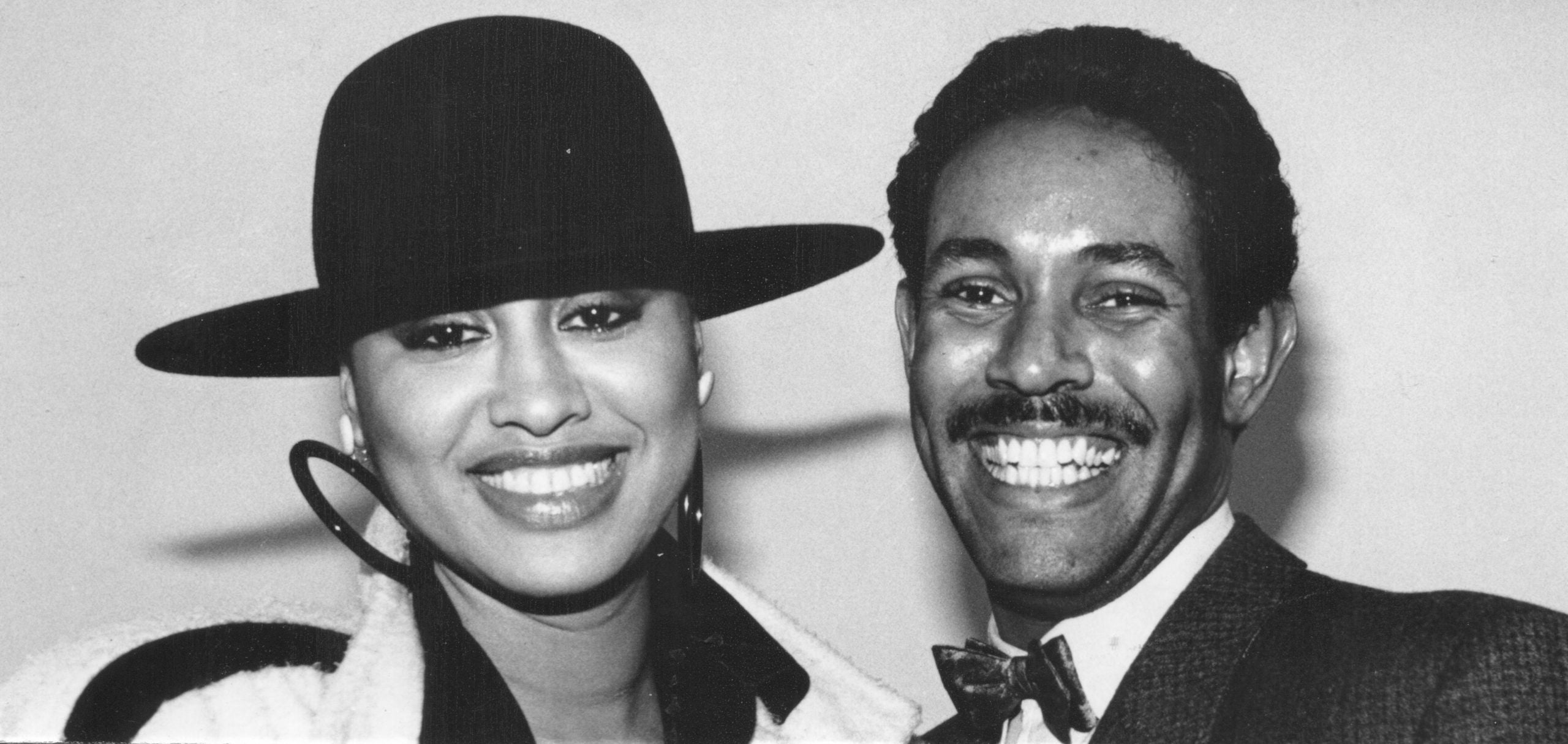

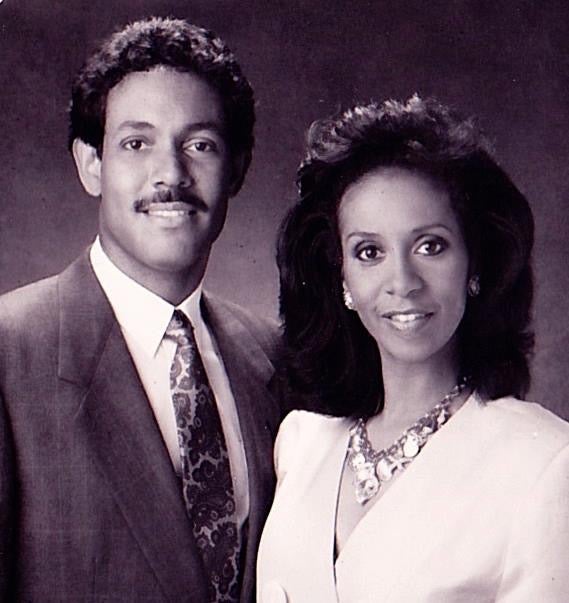

Lindsey was becoming so popular that television stations were courting him. He and jazz singer and deejay Angela Stribling became best friends as they hosted “Screen Scene” on BET together. They’d drive together to Baltimore to co-host “On Time” on WJZ-TV in Baltimore, a show that came on in the slot left open after the Oprah Winfrey-hosted “People Are Talking” was cancelled. On the weekends Stribling and Lindsey would hang out, going to concerts—their favorite live show to see was the boss Diana Ross.

“We were so close, we could have grown up in each other’s houses, that’s how much we were alike,” says Stribling. “I don’t know if a lot of people knew about his goofy sense of humor, we shared that. We would just laugh.”

His sexuality never came up, although the two were close. As Lindsey started to show signs of Kaposi sarcoma, it became hard for anyone to ignore. There was a stigma around this new fatal disease, a disease that was affecting the gay community like no other.

“I had not convinced him to go public because AIDS was something no one wanted to talk about,” says Goldson. “There was the stigma, he had elderly parents, he was so good looking and he had a huge following of women. It didn’t make sense.”

“It wasn’t until the very end, he said ‘there’s no easy way for me to say this, but I’m gay.’ I just laughed,” remembers Stribling. “I said, I know, but who cares, I love you. He started opening up about his life. He pulled out a photo album and showed me his first love. He told me his celebrity crush was Johnny Mathis. He said, ‘I just always felt like if I wasn’t gay you would have been my wife.’”

“I knew he had AIDS,” says Hughes. “I said your nose is changing color, it’s getting darker. He said, I am just suntanned. I said, no you’re sick. You need to go get checked. He later told me he had already accepted it. Two weeks before he died he called me and said, ‘I really want you to know that I appreciate everything you’ve done for me, I know I stood on your shoulders.'”

Goldson did eventually convince Lindsey to come out publicly. Most people told him how much they loved him and respected him. But there were some that would say within earshot that he got what he deserved because he was gay.

“I always told people Melvin was more man than any men I know,” says Gorham. “Being a man has to do with keeping your word, being responsible.”

From his hospital bed at Sibley Hospital, Lindsey took calls from listeners at WHUR. He was back to where he started. He thanked people for allowing him into their lives. He shared how it was to live with AIDS, how he loved his audience, all as Stribling held his hand until he took his last breath.

I always told people Melvin was more man than any men I know.

Joe Gorham

“We were playing songs and this was the first time people were hearing them,” says Dyana Williams. “People had limited choices for entertainment, no cell phones, no cable TV, they were glued to the radio. You would run out of your car to get into the house to get back to your radio.”

In the 70s, 80s and well into the 90s, this was true.

* * *

Every night I’d put a Blank cassette tape in my stereo, prepared to record songs from The Quiet Storm as I talked to my boyfriend until the sun showed up.

The songs Lindsey played bring back moments when I hear them now— like “I Just Want to Be Your Girl” by Chapter 8, featuring Anita Baker, a song we combed the D.C. streets trying to find a store that had the cassette. “Very Special” by Ronnie and Debra Laws, was a special request my high school boyfriend made on the radio. The Temprees “Dedicated” reminds me of a young man with the deepest baritone I’ve ever known and how’d he’d sing it on the telephone. Luther Vandross’s “Never Too Much” reminds me of sitting at the bus stop, already late for school, with our walkmen listening to tapes we had recorded from Melvin’s Melodies. “As You Are” with Phyllis Hyman and Pharoah Sanders is the memory of cutting school for romance and losing the day in a darkened room.

At Lindsey’s funeral, artists like Phyllis Hyman and Jean Carne not only sang with no time limits, they acknowledged that Lindsey broke them as artists. He was the reason anyone ever heard their voices.

“The Quiet Storm helped to revolutionize the sound of Black radio,” says Hughes. “The genre created classics, created standards like one of Melvin’s favorites—Nancy Wilson singing ‘Guess Who I Saw Today.’”

Howard University eventually registered the name as the Original Quiet Storm and Stribling is now the first female host of what’s now called the Original Quiet Storm on WHUR.

As President Ronald Reagan’s policies and the crack epidemic joined forces to terrorize Black communities in the 1980s, what always kept us sane was the music.

“Melvin was an ambassador of peace,” say Hughes. “The format lent peace to a chaotic existence. A psychologist told me that ‘The Quiet Storm’ brought peace in Black households. I started crying. I never thought of it like that.”

Ericka Blount Danois (@erickablount) has worked as a music and culture writer, author and producer. She is currently a fellow in the Sundance Episodic Maker’s Lab.