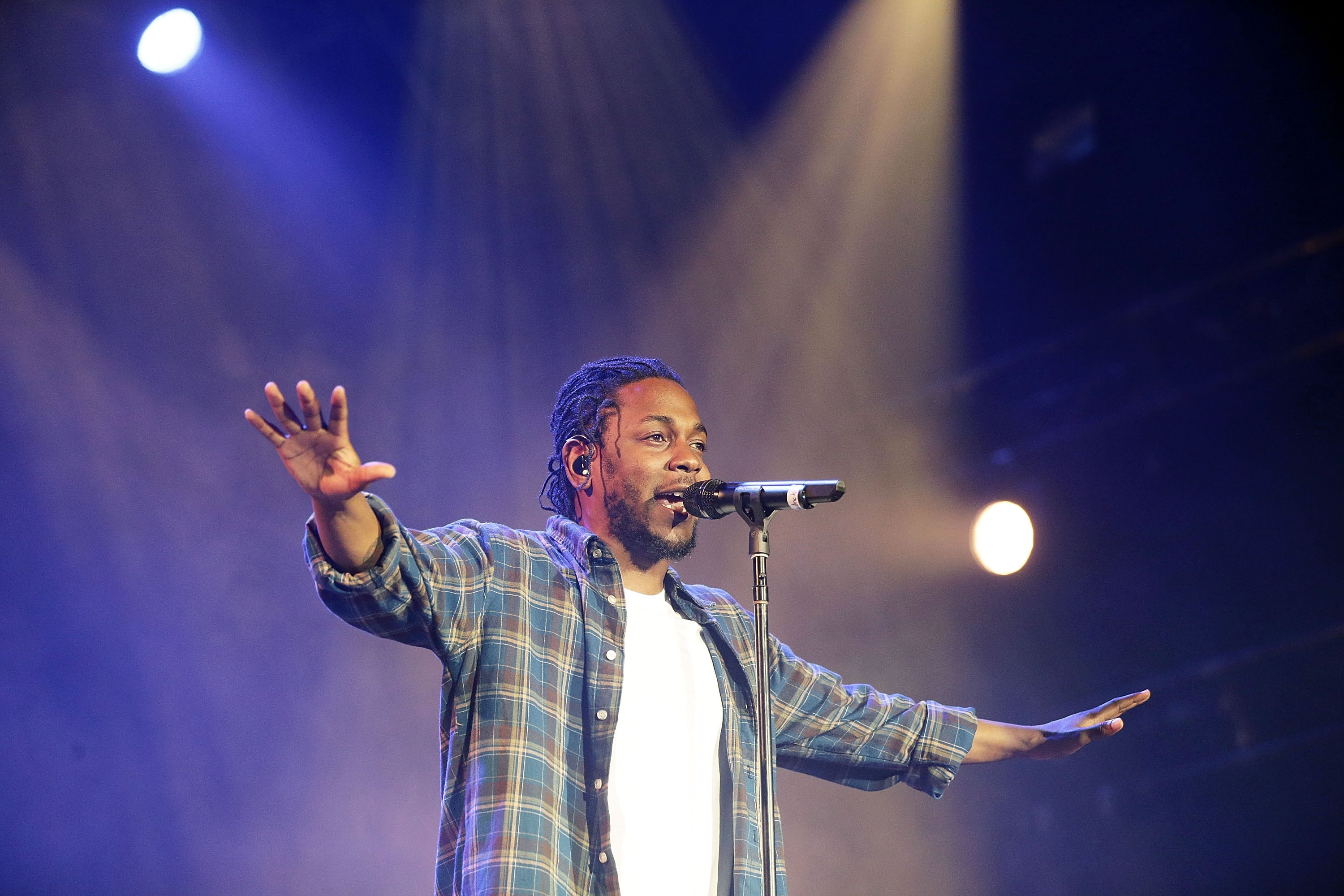

Kendrick Lamar left us shook once again after releasing visuals for his single “ELEMENT.,” a track off his platinum-selling album DAMN. The music video directed by Jonas Lindstroem & the little homies is a detailed portrait of how violence in the African American community is internalized and used to maneuver everyday life.

While the video specifically depicts shots of life in the inner city, the narrative is one Black people everywhere can relate to on some level, regardless of age or socioeconomic status. Kendrick makes plain the ways violence is institutionalized and experienced in our community. Unfortunately, it’s the backdrop to so much of Black life whether encountered firsthand, on the news or learned about through history lesson’s, we’ve all encountered it in some degree or another.

K. Dot walks us through the mechanics of navigating this space as a Black man in just 3:34 mins. It’s almost as though we’re reading K. Dot’s personal journal entry, accept far too many Black men can mirror the reality Kendrick frames. The video opens with striking shots of the elements, water, blood and fire. A hand emerges from a sea of water as if someone were beckoning to be saved from drowning, a man is laid out on the concrete profusely bleeding and a crowd of youth are standing watching a building burn. Everything is in disarray in this neighborhood you image being labeled by yellow tape. Outside of this tape there’s probably a reporter rushing to the scene without the full story and writing it off a warzone cautioning us that we shouldn’t go there. Nothing in this video speaks to a way out; instead it surfaces as a constant state of confusion and anguish.

To be alive and present in the African American community is to sit almost too close to the television screen and watch the constant reverberation of Black pain and trauma. It’s hard to get up and just go about life as usual without inheriting a survival guide. From a young age we’re cautioned with how to proceed when engaging with law enforcement and taught how to defend ourselves against the cyclical violence in our community.

The video begins with kids trying to figure out how they will maintain their youth, while protecting themselves and surviving. There are no parents or older community figureheads in the first few moments, just youth. The video then rapidly progresses, we witness a gang in a car, throwing up signs, there’s an encounter with the police and a pan to a man getting handcuffed. White media may constantly put a spotlight on our communities as though they are in flames and the violence we encounter is all self inflicted.

Violence is layered and Kendrick challenges this overly simplified explanation that can cast us as violent tropes.

Kendrick walks as though this narrative of gangs raising the next generation in our communities, perhaps because of the false assumption that gang affiliation can be equated with a sense of power and safety for some. As we watch young boys turn men, they are baptized by water into the reality of this manhood they must face.

In the Old Testament these elements were meant to symbolize agreement. Riddled throughout Damn are more Old Testament references and then things change when his cousin Carl Duckworth gives him a new perspective on religion towards the end of the 14-track album. Kendrick begins to find a new way of interpreting scripture, one that is vengeant. It’s almost as though he goes from adopting some of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to Malcolm X’s ideas on the use of violence to achieve control over one’s life, as he show the evolution of boys becoming men and the various obstacles they face.

We continue to see these three elements through the video. However, Kung Fu Kenny’s lyrics suggest a new approach to survival, “I’m willin’ to die for this sh-t, I done cried for this sh-t, might take a life for this sh-t.”

Woven between Gordon Sparks inspired shots there’s a story of a young boy being raised by his community, encountering the police, joining a gang and fighting and getting beaten. It’s all apart of this game of survival and a rough course on masculinity. It’s less of a coming of age story and more of a showcase of the performative defense mechanisms many Black men have to face simply to survive a perpetual state of violence.