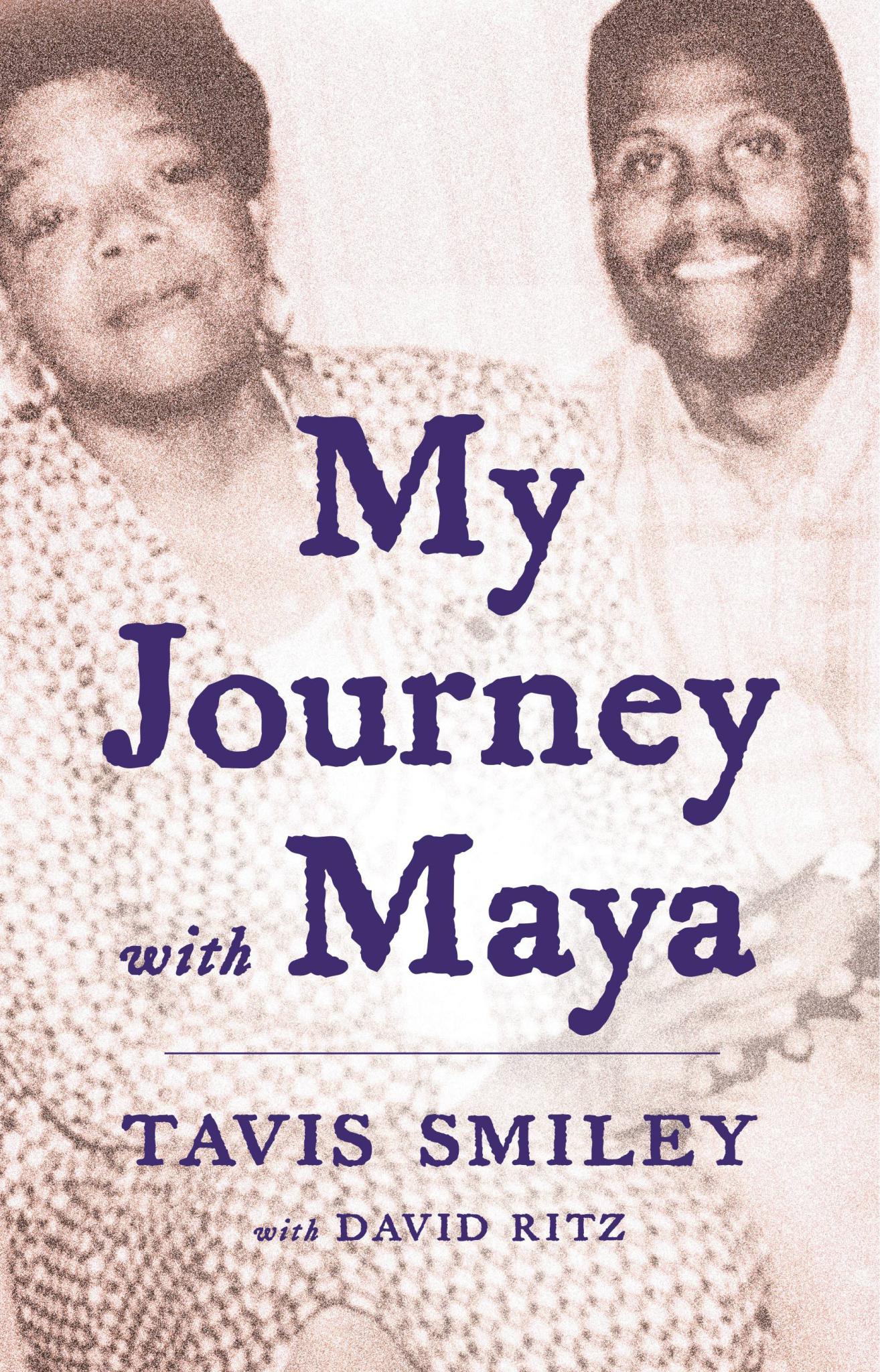

Tavis Smiley reflects on his decade-long friendship with Maya Angelou in his new book, My Journey with Maya.

Prologue

Maya Angelou and I shared a friendship that I count as one of the great blessings of my life. As you will soon see, she appeared—and kept appearing—exactly when my spirit required repair. I do not consider those appearances coincidences but rather precious gifts.

The aim of this book is to share those gifts with you. It’s a lesson Maya Angelou taught me. Maya was all about sharing. In her writing and public appearances, her soaring spirit attracted legions of loyal fans. But without minimizing those literary and televised encounters, I have to say that the personal experience—the one-on-one, face-to-face meeting with Maya—held a power all its own. Those are the meetings, whether during our journey to Africa or in her homes in Harlem and North Carolina, that I seek to bring to life in this memoir.

I do so to honor my dear friend and, to the best of my ability, give you what she gave me—words and attitudes that invigorate the soul. Maya’s great mission was to demonstrate how courageous love can heal even the deepest wounds. She taught me about bravery, about listening, about language.

The ideas expressed to me were ones she had shared—and would continue to share—with many others. She was remarkably consistent in expressing her loving vision and strategies for spiritual survival. Maya freely spread her sagacity to as many people as possible and in as many forms as possible. I was only one of many who had the good fortune to sit by her side and glean her wisdom.

When we met, I was in my twenties and Maya was in her late fifties, a strong and vital presence. During the course of our twenty-eight-year dialogue, we both faced enormous challenges and went through life-altering changes. Up close, I was privileged to see how Maya responded to those challenges and changes. And most poignantly, I was able to see how she approached what many consider the greatest trial of all: impending mortality.

Maya’s immortality rests in the beautiful body of work she left behind. Undoubtedly she will be discovered and rediscovered by generations to come. Just as Paul Robeson is remembered as the greatest Renaissance man in the history of black America—athlete, actor, activist, scholar, singer, lawyer—I believe Maya will be remembered as black America’s greatest Renaissance woman— dancer, poet, actor, screenwriter, memoirist, director, lyricist, activist.

A brief note about the form of this book:

Maya Angelou was blessed with an extraordinary voice. By quoting her, I strive to convey the haunting beauty and lilting musicality of her storytelling. She told and retold many stories, some of which you’ll read here; other conversations I recount were private and have never appeared anywhere else. In re-creating her voice for this text, I have based quotations on the copious notes I took during our private encounters, the transcripts of our many public conversations, my best recollections, and the complete written works of Maya Angelou.

I hope that by writing down for you Maya’s impact on my life I can shed new light on her luminous character. I miss her every day, and if this book lets you see her, hear her, and feel her spirit, I will be gratified—satisfied that I have done what, in both word and deed, Maya urged us all to do:

Pass on the love.

My Journey with Maya

My life was filled with purpose.

But nothing could have prepared me for what I was about to do. I had a letter to deliver to Maya Angelou. It was the early 1990s. In my senior year at Indiana University, I had sought out and miraculously persuaded Tom Bradley, the first black mayor in the history of Los Angeles, to hire me as one of his many assistants. It didn’t matter that my job assignments were mundane—filling in for the mayor at low-level ribbon-cutting ceremonies, accompanying the mayor’s wife to her medical appointments, writing countless administrative memos. I was thrilled to be working for a dedicated and powerful public servant.

Growing up in a trailer park in rural Indiana, a black kid in a white world, I had gravitated toward mentors and public servants such as Kokomo city councilman Douglas Hogan and Bloomington mayor Tomilea Allison. I liked the way they gave voice to the voiceless. I, too, wanted to champion the downtrodden. Martin Luther King Jr. was my spiritual and political hero, and I wanted to do all I could to right society’s wrongs.

It wasn’t until college that I had the chance to sit under the teachings of black instructors. In my first course in Afro-American studies, Professor Fred McElroy lectured on the subject of two women whose writing impressed me deeply—Toni Morrison and Maya Angelou. So when Ms. Morrison was scheduled to lecture at the university, I was the first to show up and take a seat in the front row. She spoke with rare eloquence. She spoke not only of the long and hallowed history of African American expression in literature, art, music, and dance but also touched upon European philosophy, Freudian psychology, and Greek mythology. Her intellectual dis-course had me reeling. So eager was I to engage her in dialogue that the moment she invited questions, mine was the first hand to pop up. I asked her about her career—certainly nothing profound. I just wanted to be part of the discussion.

I couldn’t blame Ms. Morrison for summarily dismissing me. She rolled her eyes, sighed, and gave a short, curt response. Her disdain was understandable. If I didn’t have a real question to ask, why bother? Why waste her time and the time of this assembly?

I had no follow-up. I quickly retreated, searching for a hole in the floor through which to disappear.

That marked my first experience with a world-famous intellectual.

Several years passed. I was working in Los Angeles when Mayor Bradley asked me to bring a personal letter of welcome to Dr. Maya Angelou, who was appearing before a philanthropic organization. Given my experience with Toni Morrison, you can understand why I was extremely cautious in my approach, to the point of being intimidated.

I reminded myself that I was only a glorified errand boy. Just hand-deliver the letter and leave.

When I arrived, the program had not yet begun. I found Dr. Angelou seated in front of fifty or sixty people. Surrounded by many admirers, she exuded dignity and patience as, one by one, she greeted her fans and ex-changed a few pleasantries.

Quite correctly, I said, “Dr. Angelou, it’s my privilege to present you with this letter from our mayor. He regrets that urgent city business prevents him from being here in person.”

“I understand, young man,” she said. Her eye contact was intense and sustained. “You’ll be certain to give the mayor my warmest regards.”

“I certainly will.”

The encounter ended there. For a second, I thought of telling her how much her memoirs meant to me; how deeply I loved her poetry; how I yearned to learn more about her relationship with Dr. King and Malcolm X. There were a million and one questions I yearned to ask. But knowing that this was neither the time nor the place, I turned and left. Besides, the mayor had me running to another event, which meant I couldn’t even stay for the program.

I had brushed up against greatness, and even just that brief whisper of being near Maya left me burning to see her again.

Life went on.

I was working for a meager city salary, but my personality was much bigger than my earnings. Even though I was still unable to pay off my college loans, I was a young man on fire, determined to make my mark, to somehow make a difference.

The mayor, with his strong sense of public duty, was all about practicality. And although I considered him my champion, ours was purely a professional relationship.

Unlike me, he was not given to far-reaching discussions or intellectual probing.

Because he knew of my college background in debating, Mayor Bradley allowed me to give speeches on his behalf. He also named me as one of six area coordinators who were to help him oversee the city. We acted essentially as junior mayors. I became his eyes and ears in South Los Angeles. The point of the job was to dili-gently bring the needs of the citizens to the attention of the mayor, who increasingly trusted my judgment.

I was riding high when suddenly the rug was pulled out from under me. The mayor hired a new deputy mayor, a young white boy from Harvard, who promptly restructured the system of area coordinators. Within days I lost my office in Bradley’s suite, my city car, and my secretary. I was relegated to the lowly office where, years earlier, I’d started out as an intern.

It took me a while to bring my complaint to the mayor, a man who disliked confrontations.

“I’ll return a city car to you, Tavis,” he said in his usual efficient manner, “but beyond that I won’t under-cut the authority of my deputy mayor.”

I was stuck, unsure of what to do, until Magnificent Montague, a local DJ famous for the phrase “Burn, baby, burn!” told me in his big-brotherly way, “Don’t fret, T. This is your chance to step out and do your own thing.”

My own thing had been clear to me since high school: public service. What better way to serve the public than through elective office?

Because I had made a name for myself, I decided to run for a city council seat. I’d be up against a popular incumbent, but with my energy and commitment to an all-out campaign, I didn’t see how I could lose.

Not only did I lose, I also failed to make the runoff. Friends consoled me by saying that, as a newcomer, I did well. But losing is losing, and I was down. As a competitor—and a fierce one, at that—I hit bottom. For all my burning ambition and grand plans, at twenty-six I was something of a lost soul.

Fortunately, friends rallied around me. A year or two earlier I had begun an organization of young black professionals through which I met Julianne Malveaux, a nationally syndicated columnist and economist who held a PhD from MIT. A brilliant woman, Julianne was a concerned friend. She saw that my defeat at the polls had taken its toll.

“What you need, Tavis, is a trip—something to get your mind off yourself.”

“I wouldn’t mind a trip,” I said. “But to where?” “How about going to Africa with Dr. Maya Angelou?”

“What are you talking about?” I asked Julianne. The idea was so out of nowhere that I had to hear her out. The charge of my first meeting with Maya, of her intensity and commitment to every moment, had never left me.

“Maya and I are close. We met through our mutual friend Ruth Love.”

Dr. Ruth Love, who had been superintendent of school districts in Oakland and Chicago, was one of the country’s leading educators.

“We’re both accompanying Maya next month on a trip to Ghana. Ruth and I are speaking for the National Council for Black Studies, and Maya will be delivering a major address at the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial Centre for Pan-African Culture. I’ll be talking about the global economy with a focus on the United States’ role in African development. Ruth will speak on education. Other scholars will be making presentations, including the great historian Dr. John Henrik Clarke.”

I knew o fDr. Clarke—one of the pioneers in the field of black studies.

“I’m sure Maya would love to have you come along,” said Julianne.

“What makes you so sure?”

“She thrives on meeting new people—especially intellectually curious young people.”

“I’m not sure what I’d do on the trip.” “How about carrying her bags?”

“I’d be honored. But are you sure I’d be welcome?” “Positive. This is a special trip for Maya. You might remember that she lived in the capital city, Accra. This will be something of a homecoming. You won’t want to

miss it.”

Truth was, I knew I just had to go. I really couldn’t afford it. The campaign had left me even deeper in debt than I had been before. And a round-trip ticket to Ghana cost a fortune. But when I mentioned that to Julianne, she surprised me.

“I have a ton of frequent-flyer miles, Tavis. We’ll use those to get you a ticket. I might even have enough to get you into business class.”

“Julianne, I’m flabbergasted, I really am. I don’t know what to say.”

“Just say yes.” I said yes.

“Now start reading up on Ghana.”

Ghana! By the time I put down the phone, my despondency over the lost election was gone. I ran to the library—easy access to the Internet was years away— and voraciously consumed article after article about Ghana. I also reread large portions of Dr. Angelou’s work, especially All God’s Children Need Traveling Shoes, her fifth memoir, in which she recounts the years that she lived in Accra, Ghana’s capital.

Situated in West Africa between Ivory Coast and Togo, Ghana—formerly the Gold Coast—was the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to gain independence. When Dr. Angelou moved there from Cairo in 1962, she was a thirty-four-year-old single mother with a college-age son, a woman wandering through the world on the strength of her inexhaustible spirit. Before Egypt, where she edited a newspaper, she had lived in New York and played the role of Queen in Jean Genet’s avant-garde play The Blacks. In the cast were James Earl Jones, Louis Gossett Jr., and Cicely Tyson. She had been a member of the famed Harlem Writers Guild and performed Cabaret for Freedom, which she cowrote and co-produced with Godfrey Cambridge. Also known as Miss Calypso, she was a popular dancer and singer; she appeared at the Apollo, recorded an album of her own, and performed in the film Calypso Heat Wave with Alan Arkin and Joel Grey. She wasn’t just sitting around.

In Accra, she was the center of an illustrious circle of expatriates, including Julian Mayfield, an actor, novelist, and activist. Living in exile, he became a writer for President Kwame Nkrumah, thought to be the most progressive and enlightened leader on the African continent.

It was Nkrumah who led Ghana to independence from British colonization, only five years before Dr. Angelou arrived in Accra.

From my reading about Martin Luther King Jr., I remembered that he—along with Ralph Bunche, Adam Clayton Powell Jr., A. Philip Randolph, publisher John H. Johnson, and Vice President Richard Nixon—had attended Nkrumah’s inauguration in 1957. In fact, Nkrumah, who invited Dr. and Mrs. King to a private luncheon, was the first head of state to welcome the Baptist preacher.

And it was President Nkrumah who financed the ambitious Encyclopedia Africana project, which brought the man himself—W. E. B. Du Bois—to Ghana at the age of ninety-three. Two years later, when the American government, still intent on persecuting Du Bois for his left-leaning sympathies, refused to renew his passport, he became a Ghanaian citizen.

When Dr. Angelou arrived, Du Bois and his wife, Shirley, were still living in Accra. And just as exciting to my young imagination was the fact that it was in Ghana where Dr. Angelou spent a week with Malcolm X, who had come to Africa after his life-altering pilgrimage to Mecca.

Maya’s trip was to take place in August of 1993. Only seven months earlier, Bill Clinton had requested that Dr. Angelou write and recite a poem on the occasion of his inauguration as president of the United States. Only one other poet—Robert Frost, at the inauguration of John Kennedy—had been so honored. In the long his-tory of the august ceremony, Dr. Angelou was the first woman and first person of color to read verse. She and Clinton shared Arkansas roots—he came from the little town of Hope; she had spent much of her childhood in a rural village called Stamps.

When Dr. Angelou went to the podium and in the bright light of the winter sun recited “On the Pulse of Morning,” a poem whose grand theme of radical inclusion conveyed a spirit of optimism with ringing clarity, millions of Americans leaned toward their televisions.

“The horizon leans forward,” she read, “Offering you space to place new steps of change…./ Here, on the pulse of this new day / You may have the grace to look up and out / And into your sister’s eyes, and into / Your brother’s face, your country / And say simply / Very sim-ply / With hope— / Good morning.”

In that assembly of world leaders, her presence was commanding. She owned the moment. Her delivery was effortless, her eloquence underscored by the passion of her conviction. I marveled at the utter confidence with which she spoke.

In the days before leaving for Ghana, I had trouble fall-ing asleep. This was my first time out of the country. Beyond that, though, I stayed awake with a strange feel-ing that it was all too good to be true; that somehow Julianne Malveaux and Ruth Love had been presumptuous in inviting me; and that at the last moment I’d be told that Dr. Angelou preferred not to introduce a stranger into her entourage.

But that didn’t happen. Despite my fears, the trip was on.

Julianne, Ruth, and I were on the same flight. Dr. Angelou was to arrive the next day.

On the long trip overseas, I mainly tried to keep my cool. That wasn’t easy. I felt like a little boy on the biggest adventure of his life. I wanted to jump out of my seat and shout, “The Motherland! I’m going to the Motherland!”

Instead of acting the fool, I spent most of the trip reading about Ghana, a country sometimes called an is-land of peace in a part of the world known for bloody conflict.

I started jotting down a list of questions I wanted to ask Dr. Angelou about her time in Ghana in the 1960s, a period that coincided with some of the headiest days of the American civil rights movement. How would she characterize President Nkrumah’s relationship with Dr. King? Did she and Malcolm discuss King? If so, what did Malcolm have to say about King? I knew that Dr. Angelou had worked closely with King; what was it like to be in his company? Thinking back over her long list of close friends—the illustrious people she wrote about in her memoirs—I realized there were dozens of questions I wanted to ask her about Richard Wright and Ralph Elli-son, James Baldwin and Amiri Baraka, Nina Simone and Nikki Giovanni.

As the jumbo jet droned on through the night, my notes became more and more voluminous. I realized that Dr. Angelou was a link—a living link—to much of the contemporary black cultural history that I had studied in college. There were more than a million things to ask her. My mind was overwhelmed by curiosity.

Approaching the Accra airport at the end of the long flight, I had the good judgment to crumple up my notes and throw them away. I realized that this woman was not coming to Ghana to entertain my questions. She was returning to a country she loved to see old friends and deliver a lecture. Because she was a world-renowned figure and a former resident, the local press would surely be approaching her. After granting God knows how many interviews, the last thing she’d need was another inter-view conducted by a tagalong. I needed to remember that I had volunteered to assist her, to do what she needed, to carry her bags. I needed to stay humble. In all probability there’d be little or no private time with her. My job was to stay quiet, stay out of her way, and be helpful whenever the occasion arose.

Remember what happened with Toni Morrison, I re-minded myself. Don’t play the fool. Don’t go shooting off your mouth when you have nothing to say.

Having given myself a stern lecture, I felt better. It was enough to simply experience the Motherland. That in and of itself was a gift. Anything beyond that would be gravy.

The plane landed with a thud.

Passengers around me woke up, but I hadn’t slept for a second.

At that very moment, I was farther away from home than I had ever been. And yet I heard myself saying words that made complete sense to me:

“I’m home.”

Excerpted from the book MY JOURNEY WITH MAYA by Tavis Smiley with David Ritz. Copyright (c) 2015 by Tavis Smiley. Reprinted with permission of Little, Brown and Company.