The well of 2000s nostalgia may be running dry. With every airbrushed crop top, baby pink miniature handbag and mangled movie remake, it becomes increasingly evident that the usual jackpot is little more than a rusty, empty safe—even without the lint and cobwebs. To say that we overdid the era is an understatement. Well-known fashion and beauty brands, marketing ghouls, fledgling musicians and television deities (need I go on?) squeezed every ounce of natural glamour from the early aughts. I would say it’s been hell to witness personal nostalgic interests being juiced for capitalistic gain, but that would be downplaying the actual hell that has been the recent global experience. Fortunately, pop culture contributors have a piping “new” decade to explore—one that’s not untouched but is still exciting. Welcome back to the 1970s, baby. Try not to spill any yak on your leisure suit.

Beyoncé’s Renaissance could be deemed the catalyst for appreciation of the ’70s. From the percussionist handclaps to thinned-out, breathy vocals to a production switch that makes you want to twirl in a fitted Bob Mackie gown, the superstar’s time machine successfully ushered in a freer love. Born in 1981, Beyoncé grew up with a clear reverence for the decade before her birth. I mean, the early 1980s were a bit of a continuation of the ’70s—with disco’s flame not quite extinguished and a flash of its warmth still in the room, and with Jimmy Carter wrapping up his sole sentence in the White House. Think of it like the few stragglers circling the dance floor a few moments after closing. The glitter was still on the floor, even as the bartender was sweeping up the remnants of a good time.

From Beyoncé’s first album on, she told us about the time she held dear. The crashing cymbals and heavy horns on “Crazy In Love” and the deliciously almost-raunchy nature of “Naughty Girl” were early proof of her allegiance. We also can’t ignore that her debut theatrical film role (Austin Powers in Goldmember) and her first solo single (“Work It Out”) were funny, funky odes to the 1970s. With Renaissance, though, there was no tie-in to another cultural happening. It was all her, and she proudly laid her influence bare. It caught on like wildfire, but the public had already eased into bowing down to the slinky ’70s—in more ways than one.

Channeling ’70s Soul

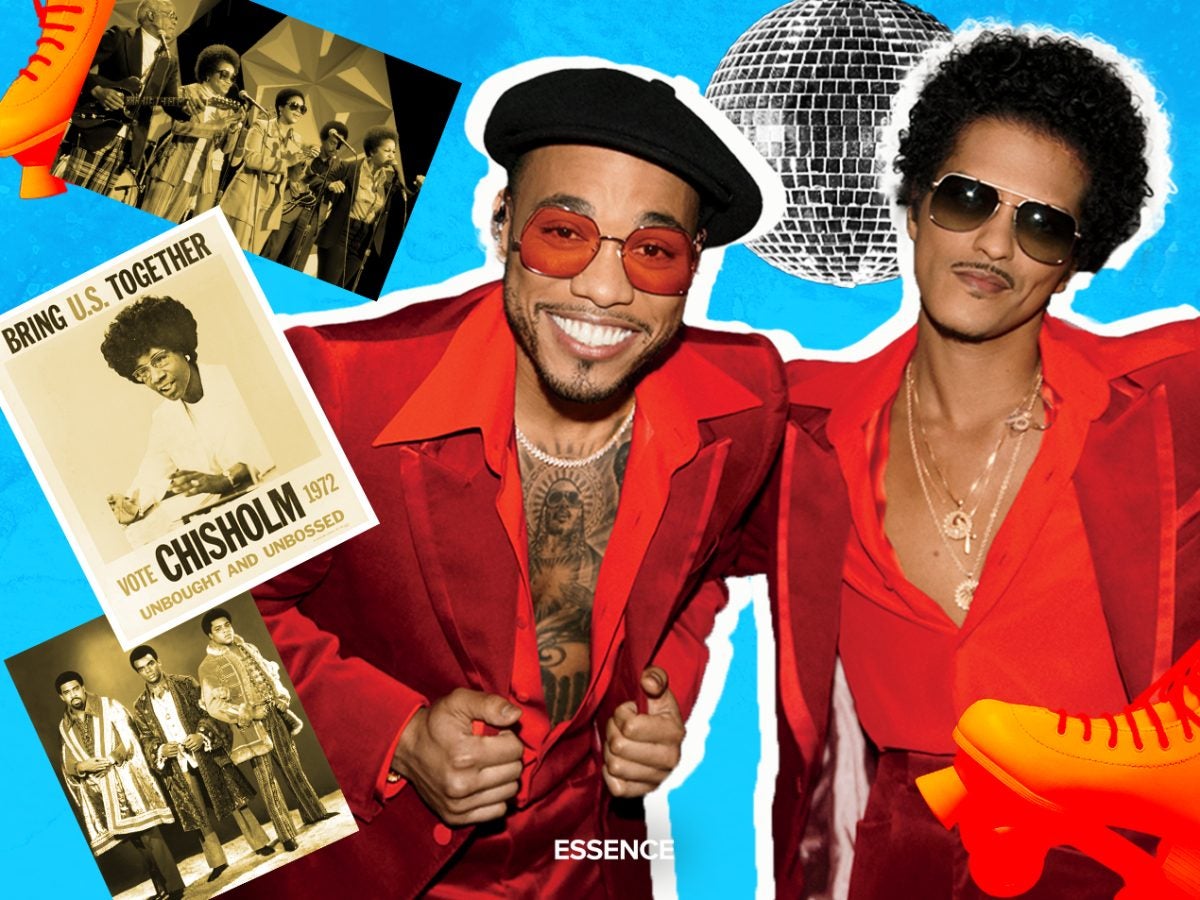

Prior to withdrawing from 2023 Grammy considerations, Silk Sonic—the musical duo composed of the always-anachronistic Bruno Mars and soul-meister Anderson .Paak—, were believed to be top contenders in the Album of the Year category. The angle for their album, An Evening with Silk Sonic, is songs you’d hear at a dimly lit roller rink in your hometown.

The duo joins performers like Kirby, Liv.e, Steve Lacy and India Shawn, who are all bringing back the soul and swagger of the ’70s. “How I wish I could travel back in time to be a voice in the cultural and love revolution that was the 1970s,” says R&B singer Shawn, “an era in music that elevated Afrocentrism, celebrated Black love and liberation, and oozed sensuality.” Her debut album, 2022’s Before We Go (Deeper), blends funk and the spirit of Motown, even pulling .Paak in for “Movin’ On.”

A songwriter, Shawn uses the lyrics of soul music’s masters as her compass. “The articulation of love in the lyrics of Stevie Wonder, Curtis Mayfield, the Isleys, Roberta Flack and Marvin Gaye felt scriptural, leaving an emotional imprint on future generations,” she says. “I think on how those artists so boldly used their voices to bring awareness to social injustices—and did so atop the funkiest bass lines! My soul’s musical mission is to carry the legacy of love, truth, freedom and power that was birthed from ’70s soul music.”

Black Women’s Voices

In the fall of 1970, thousands of women took to the streets of New York City. The group came together on the 50th anniversary of women gaining the right to vote—which Black women did not earn until 1965. The task at hand was part celebration, part call-to-action, as equality was still far from a reality.

The Women’s Strike for Equality was the brainchild of Betty Friedan, the author of the 1963 book The Feminine Mystique. The text explored the nonfulfillment of post–World War II housewives, encouraging them to find purpose in a career. But as with the women’s suffrage movement that Friedan later sought to honor, her most famous work muted the voices of Black women, most of whom were already working outside the home.

“We know that Black feminism was happening before ‘Black feminism’ ever became a term,” says Jaimee Swift, the executive director of Black Women Radicals and an assistant professor of political science at James Madison University. “In the 1970s, you were finding people, particularly Black women, emerging from the Civil Rights era. Black women were coming from the church, coming from these organizations, but they were not being heard. Then they go to this cadre of White feminists, and they’re not being heard where they are, either.”

If the second wave of feminism arrived in 1970, stamped by the Women’s Strike in August of that year, the Me Too movement has been deemed the fourth wave of feminism. In essence, Me Too was an opportunity for women to speak out about the sexual violence they faced, especially in corporate and entertainment spaces. Though detractors have tried to dilute the movement and rope the cause in with “cancel culture,” it is still a force of justice reverberating through Hollywood.

It was a Black feminist activist, Tarana Burke, who coined the phrase “Me Too” and gave the movement its framework. She has remained focused on giving voice to Black and Brown women and girls who are survivors of sexual violence. Yet when actress Alyssa Milano tweeted about Me Too in October 2017, the general public was unaware of Burke’s work. Though Burke has since been credited for her efforts, the origin of Me Too is still fuzzy for some people. Once again, Black women are having to fight to be heard.

Power Suits In Vogue

“They say style repeats itself every 20 years, but I believe the style of the ’70s is something that’s stuck around since its debut,” says Bri Malandro, a pop-culture archivist, “from the flare jeans to the crop tops to layered haircuts with flipped ends and platform heels.”

My grandmother, Delores, a proud woman with a sharp tongue and a killer closet, turned 20 in March 1972. She doesn’t believe in getting rid of clothes. Gray suede boots, a mustard leather skirt and loosely fitted plaid tops still take up space in her closet—not because she likes to hold on to things too tightly, but because she knows garments always come back in vogue.

“Every woman needs a good pantsuit” is something my grandmother has been saying to me since my teens. According to my social media timelines, she’s right. For Michael Kors’s Fall-Winter 2022 collection, the luxury brand placed model Adut Akech in a breathable marigold pantsuit. Three hours before I first typed this, fashion retailer Nasty Gal shared a post of a fashion influencer wearing their olive green faux-leather suit. Creeping to their website will let you see their velvet flared pants leg and satin and belted blazers.

According to Elle magazine, America is returning to the office—and thus power suits are on the rise. New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman predicted the power suit’s return back in May, writing, “Odds are the tailored blazer and suit are about to make a comeback, judging from the recent Balenciaga show held at the New York Stock Exchange, which was heavy on the white collar–wear. Not to mention the variety of jackets visible even on the red carpet in Cannes.”

This echoes a time when the number of Black women in clerical roles was on the uptick, and the need for suits was rising, too. The Instagram hashtag “70s Fashion” also includes over 1.5 million posts of striped sweaters, floral prints and corduroy bucket hats. Who said you can’t add spice to a suit?

Unbought and Unbossed

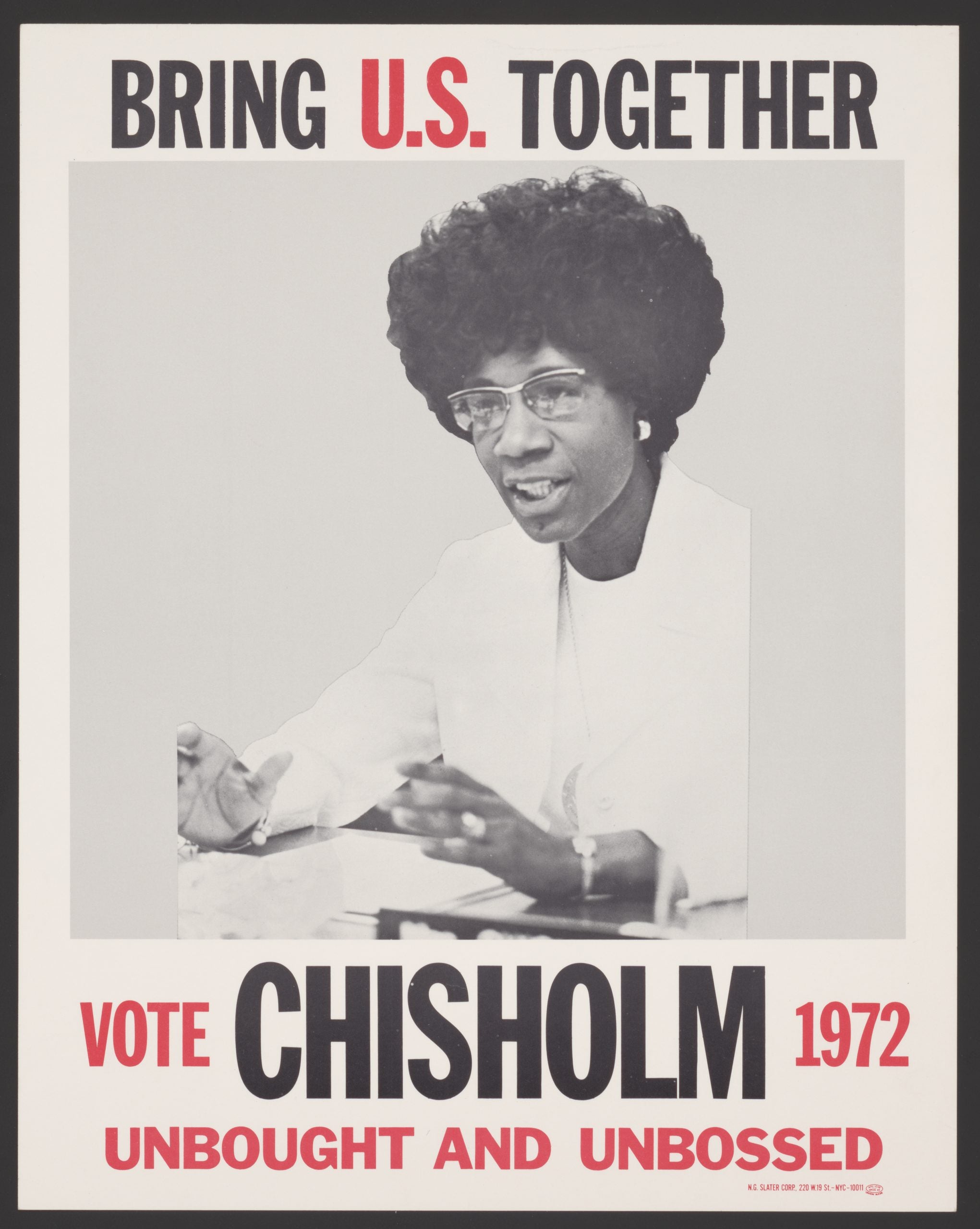

Shirley Chisholm made history in 1968 when she became the first Black woman nominated to Congress. Four years later, she made an even more daring political move when she ran for president. Though she lost the Democratic nomination to George McGovern, her campaign ushered in an unprecedented number of Black women in political office.

“I think having had the courage and the political will to be a fiercely independent, as she said, ‘unbossed and unbought’ candidate paved the way for Black women running for anything after that,” says Crystal Hudson, a councilmember for New York City’s 35th City Council district.

When I ask Hudson about the political parallels between the 1970s and 2022, she comments, “I think about the environment that folks were in then and the environment that we are in now. You were coming out of the Civil Rights Movement then. You were coming out of protests against the Vietnam War. Now we’re coming out of a global pandemic, Black Lives Matter protests after George Floyd’s murder, the fall of Roe v. Wade—it feels like similar times. It also speaks to those moments when there’s so much going on that creates opportunities for people like us to be in elected office.”

January 2023 would have marked 50 years of Roe v. Wade, the landmark 1973 court ruling legalizing abortions. This past June, the current majority-conservative Supreme Court overturned the decision, unnerving citizens nationwide. The consequences have been swift and unrelenting: Children impregnated by pedophiles have become the center of polarizing political conversations, rather than being seen exclusively as the victims of a sickening crime.

In all of our glorious dancing and dressing and marching and running for political office, the societal needle has moved little in 50 years. Has it been here all along, this falsified progress? I believe we felt just enough change to keep pushing—but enough unrest to wail. Each decade, we hope against hope that we are wiser than the people before us. We study their pitfalls, their fears and their desires. With the world at our fingertips, we puff out our chests, confident we can be better. But the systems that fettered our ancestors chain us, too. Maybe a renaissance is exactly what we need.