For Sam Pollard, The League is far more than a documentary.

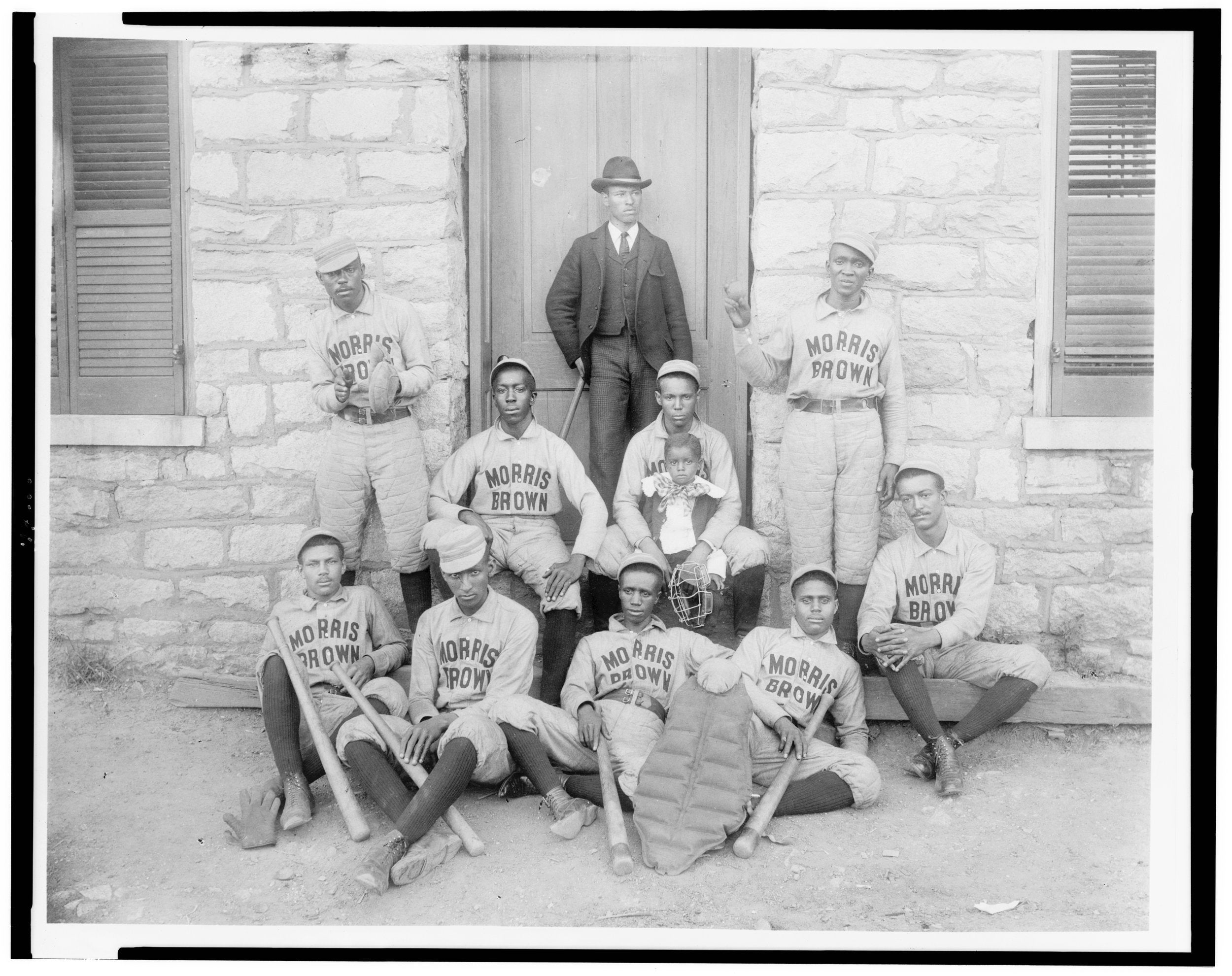

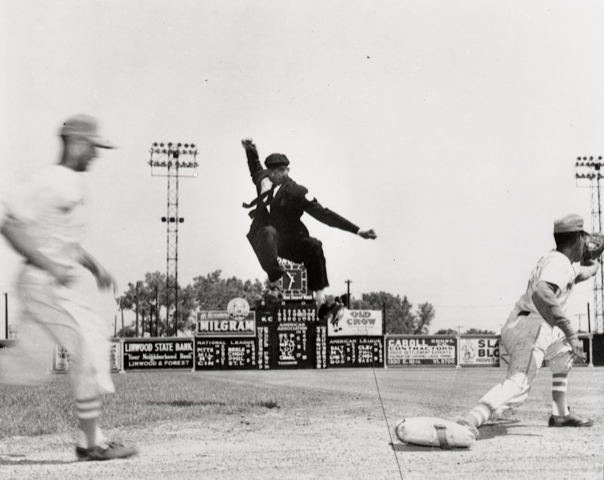

As with many things, Negro League baseball was born out of necessity. In the late 1800s, Black people were not able to play in major and minor baseball leagues due to racism, so they formed their own teams, creating a place where some of the best athletes in the world would be able to showcase their talents in a welcoming environment. While 60 years have passed since the last Negro League game was played, accounts of legendary games and larger-than-life players can still be heard. Pollard seeks to introduce this powerful story to a new generation, and highlight figures that were important to its success.

“This is an important story that should be told,” Pollard says. “It’s not just an African American story, it’s an American story. Viewers are going to learn so much about the Negro League, Effa Manley, and so many others that were critical in the league’s history.”

Executive produced by Academy Award-winning director and foundational member of The Roots Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, Tariq Trotter, and produced by RadicalMedia, this documentary chronicles the dynamic history of the Negro Leagues, along with it’s social and ecomonic impact on surrounding communities. The League also examines the effect of integration not only on the game, but in life off the field.

ESSENCE spoke to Pollard about this groudbreaking film, the Negro League’s lasting legacy and documentary was created.

ESSENCE: Why is telling the story of the Negro League so important to you?

Sam Pollard: I think it’s important because it’s a part of American history that most people aren’t aware of in the 20th century. I always feel a responsibility to tell our story and to make people understand that our stories are part of the American story. When I was approached about doing this film, I just thought, “This is a way to get this out there,” so people knew about it. I knew a little bit about it growing up, but this is a way to really dig into it and let people understand the evolution of the Negro League and some of the great players and owners who were involved in the experiences over 40 years.

Tell me, what was the production process like for the League, and how were you able to gather so much archival footage for the film?

Well, originally, I was approached about 10 years ago by a gentleman named Byron Motley, whose dad, Bob Motley, had been a Negro League umpire in the late ’40s and ’50s. They wrote a book about his dad’s adventures, and then Byron thought it should be a film. He had interviewed, over the years, a series of former Negro League players. He reached out to me and he asked me if I was interested in directing it, and I said I was, so we started that long journey. It took a while – about seven years. Then we hired an archival producer, a woman named Helen Russell, who did a really fantastic job in locating material that we didn’t know about; pictures, placards and stills. Then we lined up a bunch of people to interview with stories, people who really loved the Negro League, and then we started up production. It was a long period, but it was worth it to tell the story.

I know there’s been a correlation between the Negro League and the Civil Rights Movement as well. How do you think the Negro League and its players contributed to the Civil Rights Movement at the time?

Well, I think, after World War II, with African Americans fighting across the seas, fighting the Nazis, fighting the Japanese, fighting the Italians, and feeling like if they’re going to give their lives for America, they should be treated as equal citizens. When they came back, there was a real push for equal rights and citizenship, and not only in terms of housing and education but also we saw in 1947 when Major Leagues reached out and found Jackie Robinson, which is an opportunity for African Americans to become a part of the American great national pastime: baseball.

I want to talk about the topic of integration. What was the impact of integration on the Negro League, and do you feel as though it was something that was necessary?

Well, this whole dialogue about integration versus segregation is one that’s a constant in American history. We didn’t want to be treated as second-class citizens. We wanted to be treated as first-class citizens, which meant a level of integration, both from an economic perspective and from an education perspective. Now, the downside to integration for many Black communities around the country after the 1950s was that they started to fall apart. Think about it this way: during the years that preceded segregation, all Black people were a unified community. Could be working-class people. Could be professionals, doctors, lawyers, teachers. So everybody within the community succeeded, even though there was segregation, those communities were able to thrive from an economic perspective and a cultural perspective.

Now, when integration really started to take hold in the ’60s, those communities lost their professional people. Those communities lost economic power, and other things that helped those communities prosper. Black people could move out of the community. They could travel, and they could go and shop in other stores. The economic engine that had been a part of these communities during segregation was no longer there, so they struggled, and we’ve seen the struggle. We’ve seen the struggle in Harlem and Brownsville; in many Black communities around the country. It’s sort of a double-edged sword: we wanted to be treated as first-class citizens, we wanted to be a part of America, we wanted to be integrated in America, but at what price?

I wanted to talk about the story of Effa Manley. To you, what made her story so compelling, and how important to you was it to do justice to her story as well?

Well, I didn’t know about Effa Manley until I became involved in this film, and she was phenomenal. There’s a whole discussion: was she of African American descent, or was she a white woman passing? No one really knows, but she grew up in Harlem, she grew up in a Black community, she became a co-owner of the Newark Eagles with her husband, Abe Manley, and she became a very fanatical baseball lover. She supported her team and was part of the engine that helped her team win the 1946 Negro League World Series.

But the thing that makes her really stand out, as far as I’m concerned, was that when Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, and Don Newcombe, he did not feel a responsibility to compensate the Negro League owners for these players that he was signing. Though she knew the League owners, she made a big noise about it, and said, “This was unfair. They should really be considering compensating these Negro League owners.” She was able to go to the Cleveland Indians, who wanted to sign Larry Doby, and she was able to get Bill Veeck to give her $10,000 as compensation for the services of Larry Doby becoming the first African American baseball player to play in the American League.

She is probably, I think, the only woman in the Baseball Hall of Fame. She was so extraordinary and so powerful. I think this is a great opportunity now to really know her story and learn about how important she was to the Negro Leagues.

For you, what do you feel is the lasting legacy of the Negro League?

Well, the lasting legacy is the lesser known players that changed through the leagues, from Rube Foster, who was not only a great pitcher but a manager and owner; Satchel Paige, one of the greatest pitchers of all time in baseball, not just in the Negro League; Josh Gibson, the great home-run hitter in history; these extraordinary players who came up through the Negro League, and they did it because by they time baseball integrated, they had gotten older.

Then, you think about the legacy of some of those younger players who came into the Negro League near the end of the League who went on to have extraordinary Major League careers. Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks. These extraordinary players who really, really turned baseball around when they got into the Major League.