Giddy up, ya’ll. Over the weekend, Stagecoach, California’s largest Country music festival, saw one of its most diverse lineups since its inception, with nine Black acts featured across three days. Essence had boots on the ground this weekend, sitting with six of these artists, each of whom affirmed in their own ways: Country music is for everybody, but it’s especially for Black people.

Tanner Adell, Leon Bridges, Miko Marks, Willie Jones, Brittney Spencer, The War and Treaty, RVSHVD, Shaboozey, and even Wiz Khalifa graced Stagecoach 2024 with their own sets for the first time. This wave of “firsts” brought with it an electrifying energy to the Stagecoach stages; “a returning to” Country, as Michael Trotter Jr. of The War and Treaty frames it.

Stagecoach had never been on my radar despite being a California local – that is, until I saw this year’s lineup. While on the festival grounds, I experienced a handful of less-than-friendly encounters, politically coded chants, and comments rooted in exoticized fascination (we all know the kind), all of which were to be expected for the territory. But, I also experienced many beautiful moments that displayed how diverse, collective, and welcoming the Country space is. Black festival-goers seemed to naturally gravitate towards each other, with one North Carolinian spotting me out in the crowd and sharing how after attending Stagecoach for ten years, he’s overjoyed to see more of our community embracing a genre we have long-standing roots in.

For an artist like Willie Jones, seeing the reception and support of Black country artists “is a dream come true,” and pushes him to want even more for the collective. In conversation, each artist pointedly named another, singing each other’s praises and showing in real time what support for their small-knit community looks like. From Randy Savvy and the Compton Cowboys spreading Black cowboy culture awareness to Marks recounting how the Bill Pickett Rodeo gave her her first platform, so many facets of Black country culture came together to lift each other up.

The mutual feeling expressed by each performer can only be described as elation. To Spencer, being embraced on that stage for her artistry felt, “empowering [to see] the future of country music make space for different kinds of people.”

The Stagecoach platform provides an opportunity to connect with country fans and show them that, “we’re here,” as Shaboozey enthuses. They delve into how it feels to perform for audiences that may not always reflect them physically. Some express the occasional discomfort while others describe their goals of creating a universal experience through music that transcends physical identity. Spencer highlights how as Black people, “we listen to music where we see ourselves,” and echoes the interests of the collective who aim to show the community that this too can be possible in Country music. Trotter expresses, “not only do we want [the Black community] at our shows, we need them there.”

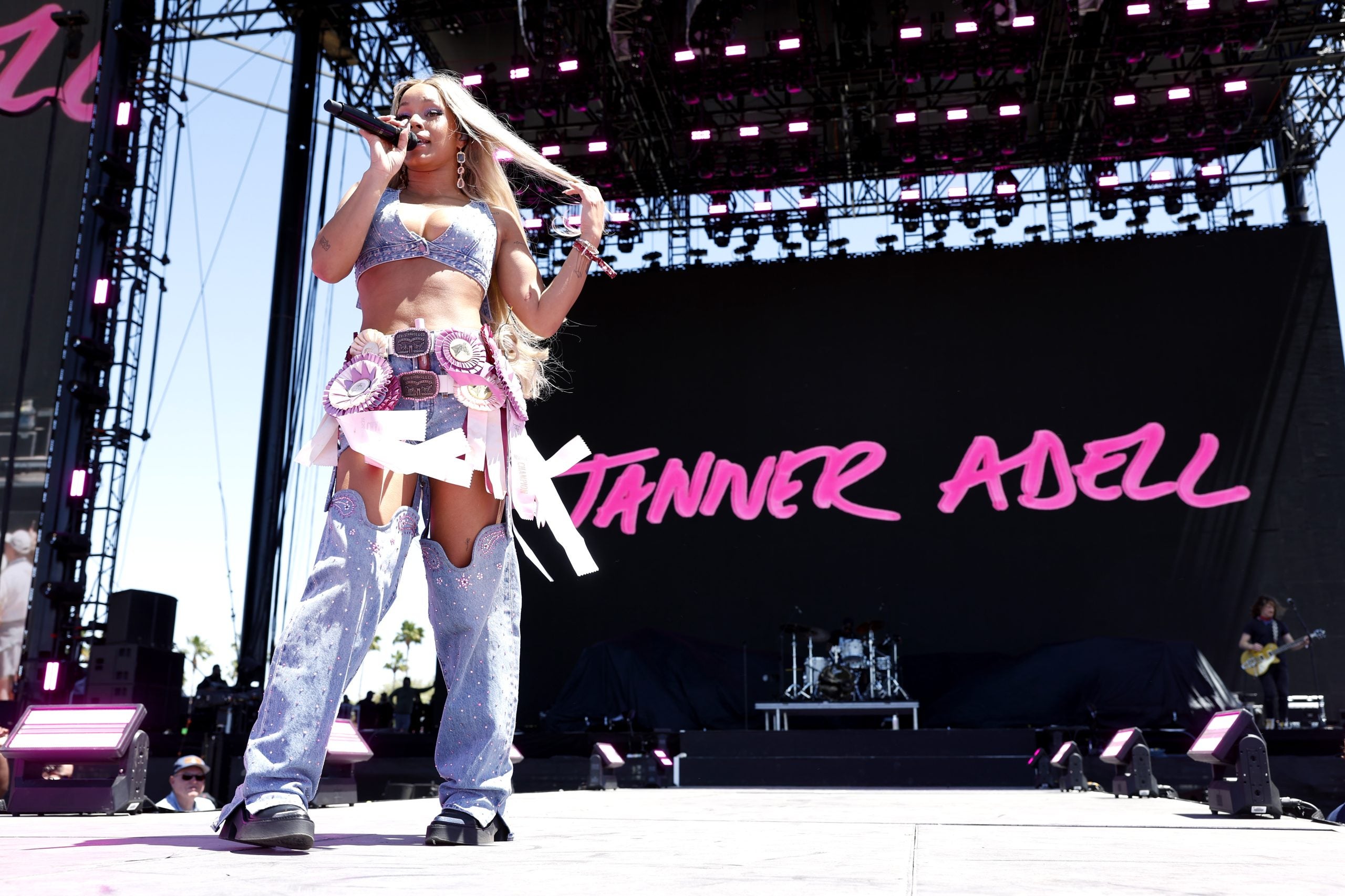

Adell focuses on curating an authentic space for her audience, “For me, I want to show up in ways that I don’t have to [explain] why I did something,” she affirms as she references her choices to wear bantu knots to the CMT Awards or bring out the Harbin Sisters, six black girls, to dance with her on the Stagecoach stage. “I did that because, the people who need to see that, if you know, you know, and they knew. And if you didn’t, then it wasn’t the message for you.” Her Stagecoach set was earlier in the day, and was still met with the most vibrant of crowds, “that just speaks volumes about [the presence of] the Black community.” She goes on to say, “women alone have a harder time breaking through in country music, let alone women of color. I’m grateful for our community.”

Reclaiming a space that has long been defined by homogenous gatekeepers can be taxing, as Marks underlines in speaking to her ten-year hiatus from the genre. “I was just heartbroken because Nashville and the industry wasn’t accepting. They loved the music, but they didn’t like me and how I presented it.” As a “seasoned” figure in this genre, she speaks to how beautiful her return has been, how she’s evolved since, and reflects on this era of country music now. As grateful as she is for the heightened focus they are currently experiencing (thank you Cowboy Carter!) she also wants Black artists to be respected for the work they’ve been putting in.

The Cowboy Carter alumni present discuss what they’ve taken from the collaboration and where they aim to go. Jones appreciates the organization that went into the creative process, Adell has learned the art of applying confident patience to her work, and Spencer definitively states that she’s learned “I belong.” Among much else, Beyoncé’s Cowboy Carter has shown what expansive qualities Black musicians bring to the genre when they aren’t boxed in.

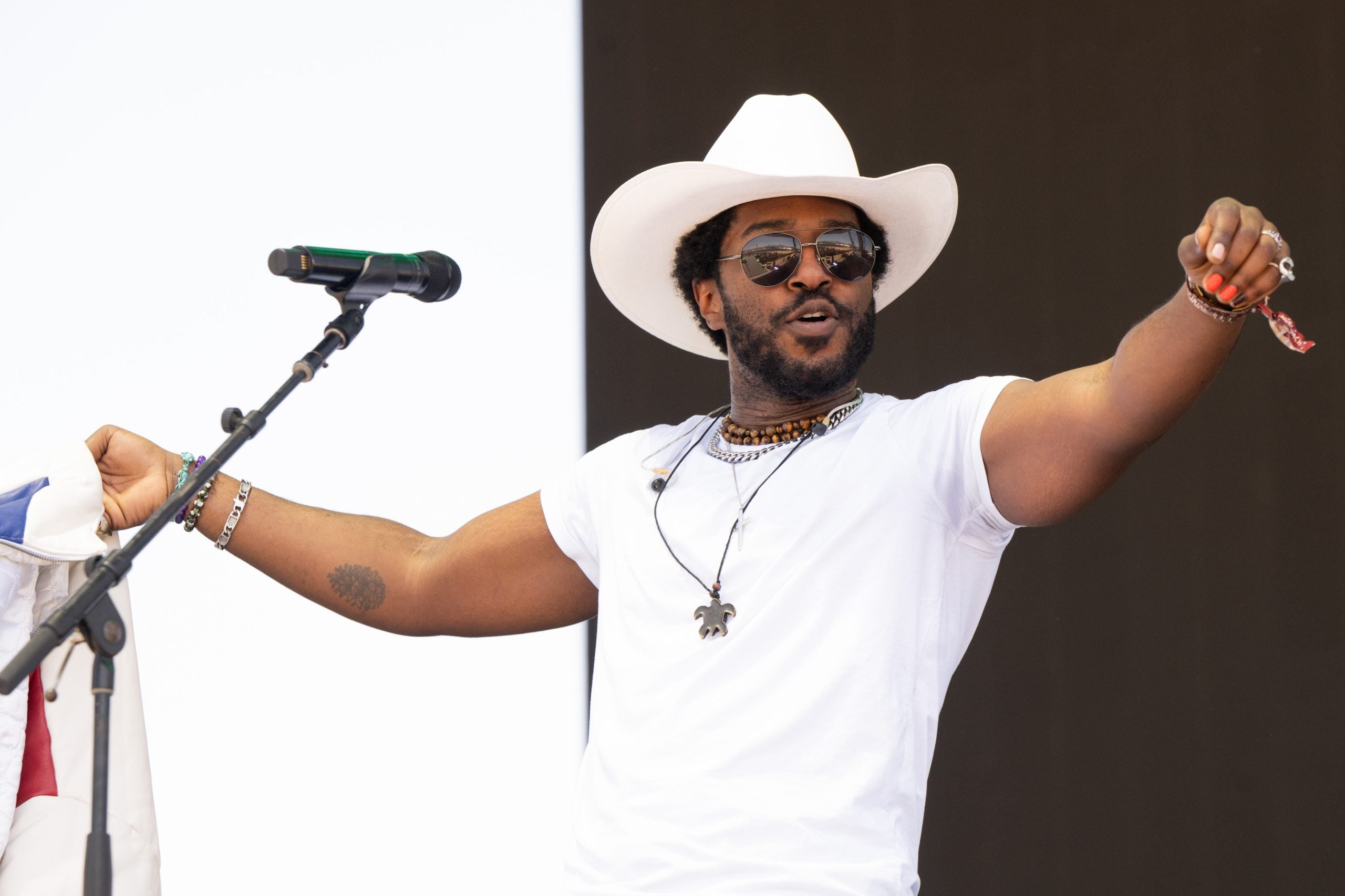

On navigating spaces where others attempt to restrain him, Willie Jones states that he simply “doesn’t give a f*ck.” Jones is refreshingly himself in every room he enters, as he made immediately evident upon sitting down with Essence. He speaks to his love of what he calls, “cultured country,” talks about his excitement for what Black musicians bring to the table, and pays little mind to the close-minded bubbles.

“Music doesn’t have any bounds. I’m doing it for the ancestors, for Shreveport, Louisiana,” Jones says. His music is heavily influenced by that classic Country sound, as well as Southern Hip-Hop. While this lends to an enticing sound that he welcomes all to enjoy, Jones also wanted Essence readers to know that he is, in fact, “for the gworls.”

The War and Treaty describe how they face the obstacles set before them and boil it down to this: love, unity, and discernment. Their love for the music, their calling, and each other is more than palpable. Tanya Trotter, one half of the powerful duo, explains the industry’s attempts to box her in as she transitioned from R&B to country music. “I wanted to do something different,” she expresses, and with one of her only examples of Black women in the space being Tracy Chapman, she emphasizes how important it is to be steadfast in yourself and your purpose.

She highlights the broader industry’s tendency to label all Black artists as R&B, and points to Brittney Spencer, the Baltimore native who firmly presents herself as a country artist. “It’s beautiful and it’s challenging,” Spencer offers. Black artists are often saddled with additional pressures or labels due to a racial identity completely out of their control. Where they should be able to express art without the lens of their identity influencing so much, this is not the case, especially in Country music. On the other hand, this very identity informs and enhances the art they put forth.

The Trotters discuss the connectivity that is rooted in the Black musical tradition, “you don’t get country music without the blues; blues without jazz and folk; and you don’t get none of it without gospel and Negro spirituals. I think that there’s some reeducation and deconstruction that needs to happen. We have to stop thinking that it’s not for us.” Marks adds that she wants Black audiences “to know that country music is part of our heritage and our being, so go forth knowing that your roots are grounded in this music.”

Many of these artists are no stranger to genre-blending. From the aforementioned genres to hip hop and Americana, their masterful versatility sets them apart from the crowd, while also connecting them with the larger tradition of Black music. As Miko Marks describes for herself, “the basis of all that I do is Black music. That’s country, gospel, R&B, bluegrass, jazz, because we are the foundation of what was created. I don’t believe in being bound by a genre.”

Shaboozey shares similar sentiments, “I’ve had so many eras,” he tells the crowd at his set, “but [the support] means so much to me.” He expands on the broader connections of the diaspora such as the origins of the banjo to West Africa, and how this history has informed his own creative process. He attributes his ability to organically fold in his eclectic taste and sound to his Nigerian and Southern identities. “African music and country music is world music. It’s the sharing of stories. [My identities] allow me to see the beauty and culture in everything around me.” After a decade of natural progression, Shaboozey’s powerful voice has carried him to this moment.

If Stagecoach’s response to these Black musicians is any indication of where the industry is headed, the future looks brighter. Tanner Adell had determined fans rushing across the fields to make her set, The War and Treaty’s soulful voices filled the campgrounds and took us to church that Sunday afternoon, and Brittney Spencer’s raw talent and vulnerability made everyone in her audience feel like, as she sings, a “homegirl”.

Willie Jones’ rich personality and voice shined through his lively set on the Mane Stage, Shaboozey’s surprise performance was met with a packed out crowd, RVSHVD’s buzzing, multi-generational audience sang along to every lyric, and Leon Bridges couldn’t utter a word without his audience erupting each time. The Compton Cowboys contributed to this atmosphere by providing cultural lessons and Q&A chats to all people interested in Black Western culture’s rich history.

It’s safe to say: The Yee-Haw Agenda is in full effect. For those of you who haven’t yet taken the leap, or are just starting to dip into the waters, this incredible lineup of Black Country stars is an excellent place to start. Now this ain’t Texas — it’s Stagecoach, but we’re out here.