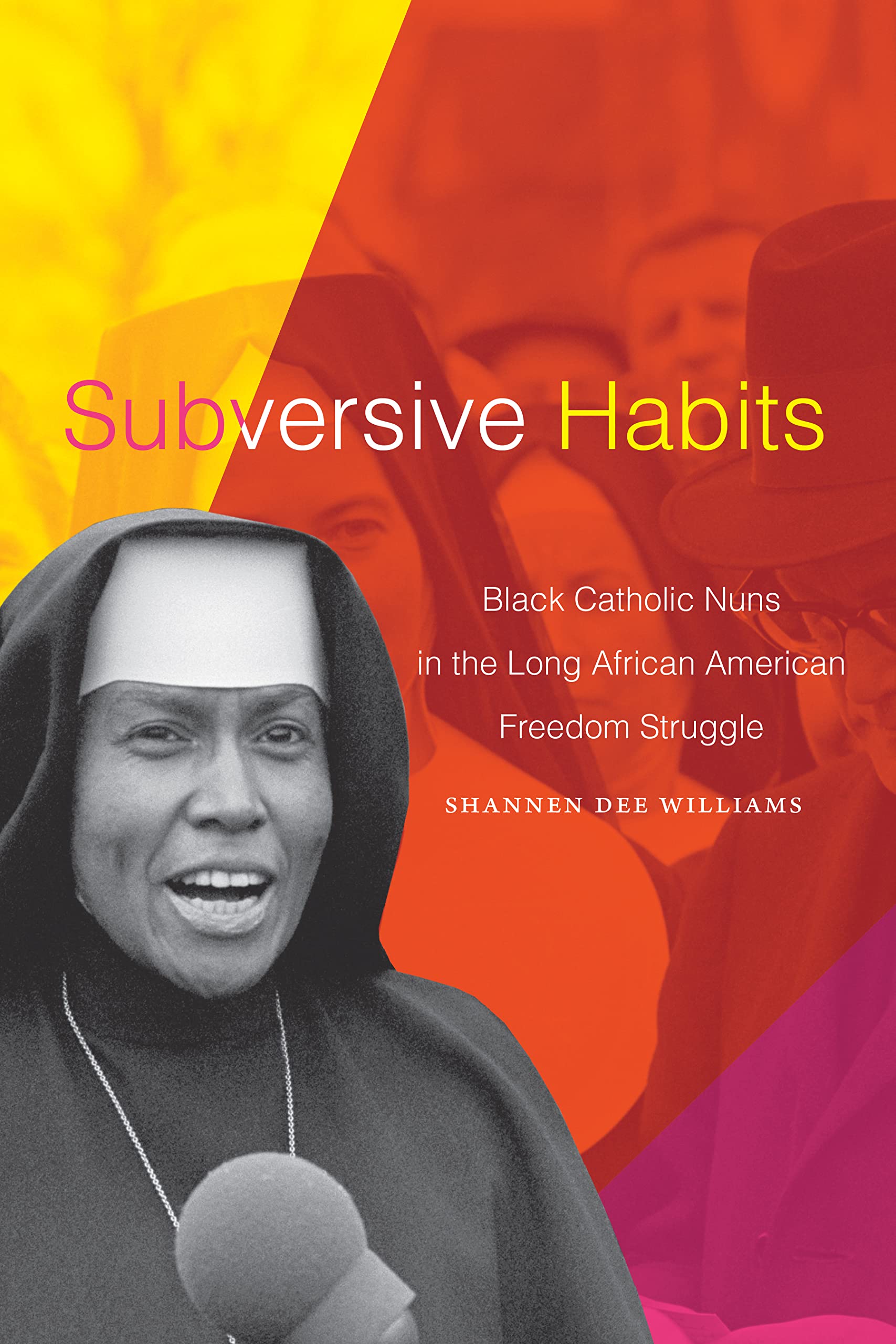

For many of us, our only reference for a Black nun is Whoopi Goldberg as Sister Mary Clarence in the Sister Act franchise. But Shannen D. Williams’ Subversive Habits: Black Catholic Nuns in the Long African American Freedom Struggle tells the real story of America’s Sister Act.

Williams grew up in a Catholic church. Her mother was one of the first three Black women to graduate from Notre Dame, a Catholic university, and even she had never seen a Black nun in person. In fact, she didn’t know they existed until 2007.

Williams describes her research into Black nuns as “provincial serendipity.” The Associate Professor of History at the University of Dayton was searching for a topic she could submit as a seminar for her class with Dr. Deborah Gray White when she stumbled upon an article announcing a Black Power Federation of Black nuns called the National Black Sisters Conference in Pittsburgh in 1968.

After Williams saw the article, she went on a journey to understand why these Black women had been so invisible. And she wanted to know what these women’s stories said about her own place as a Black woman in the Catholic church.

When I asked Williams why she thinks these stories have been so obscured she says plainly, “There’s no way to tell Black sisters stories without confronting the church’s largely unacknowledged and unreconciled histories of colonialism, slavery and segregation.”

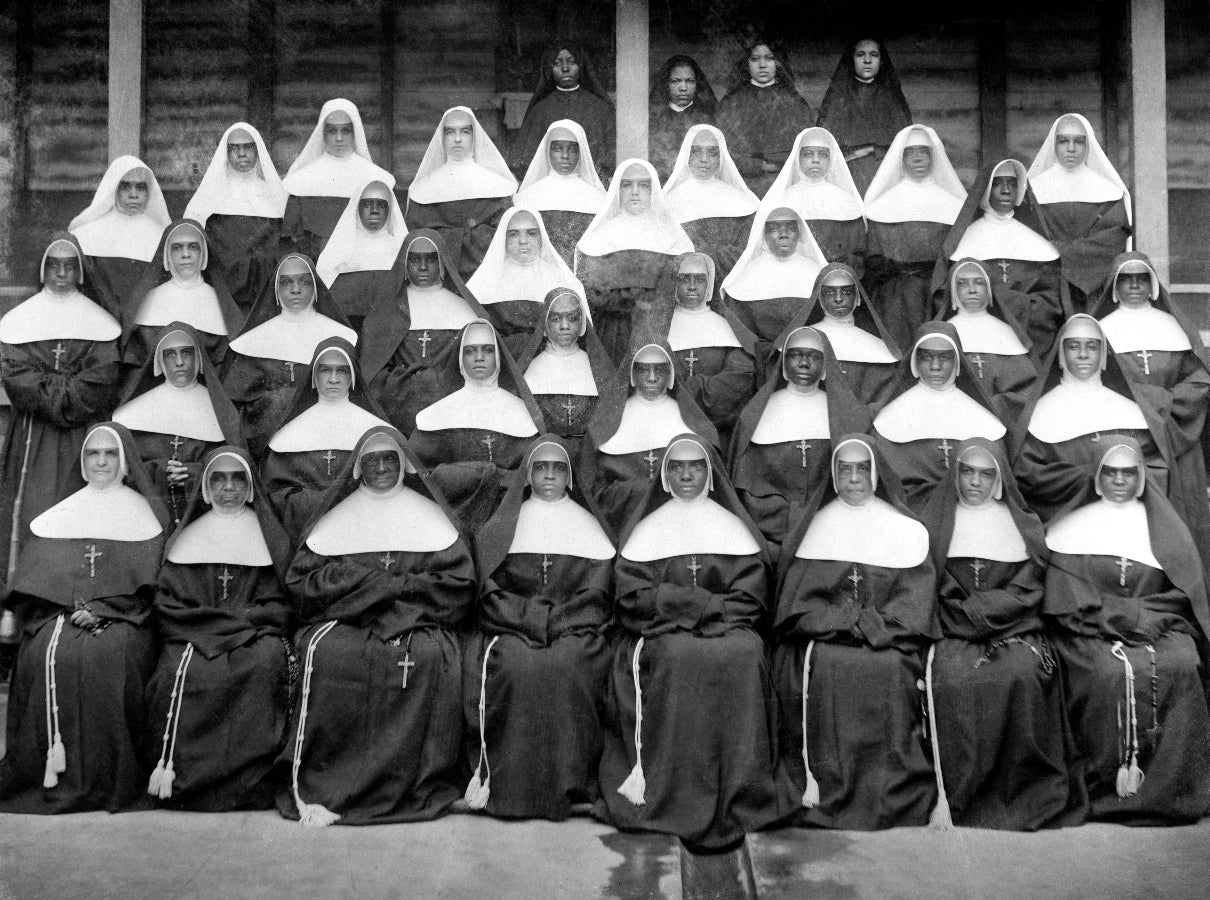

Williams’ research found that the nation’s Black sisterhoods were founded because the white and European congregations of nuns refused to admit women of African descent solely on the basis of race. For an institution that has declared itself as “universal and open to all,” that reality is a dangerous memory.

While it might be a painful acknowledgement for the church, Williams says Black people, Catholic or not, can look to Black nuns as a source of inspiration. She calls these sisters the “forgotten prophets.” Not only did these women, living in a slave society, belonging to a church that was responsible for the transatlantic slave trade, dare to take the sacred vows of chastity, poverty and obedience, they worked to rebuild in areas heavily associated with the sins of slavery.

Black nuns bought a slave trader’s pin and turned it into a school. They launched social service ministries, freely open to African descended people like schools, nursing homes, orphanages. Black nuns, Williams research found, would become desegregation frontrunners and foot soldiers.

“They desegregate a host of Catholic colleges and universities long before The Brown v. Board decision,” Williams says. “Then they begin to desegregate a host of white sisterhoods after World War II, then go on to desegregate a host of other Catholic institutions. And these are women who are doing this without the protection of news cameras.”

This work was not easy or safe when many Catholic institutions exist in sundown towns or all-white neighborhoods that are notoriously hostile to Black people.

For Williams, a historian of the African American experience, the fact that she didn’t know this vital history was astounding. Particularly because the Black sisters left records. They’ve just been overlooked.

“No one has wanted to touch it because it explodes all these myths we’ve said about Catholic church, in particular the ways in which white sisters have been characterized as the most progressive of church representatives on racial justice,” Williams explains. “When in fact, if we tell Black sisters’ stories, nothing could be further from the truth.”

In her research, Williams found that there were white orders of nuns who went to great lengths to evade desegregation by any means necessary. Even sisters who had been educated by white nuns were later denied entry into their orders.

“They put race before faith,” Williams says.

The phenomena of educating Black children has been a way for the Catholic church to defend itself against accusations of racism. But that doesn’t tell the full story.

“A small number of sympathetic white priests begged European sisters and white sisters to begin to minister to the African American community,” Williams explains. “That is why we see a white ministry to African Americans. They see this work as–oftentimes they describe it as repugnant work.”

Williams is not suggesting that the white nuns were not sincere in educating and ministering to Black people. But she acknowledges that these nuns are often bitter and violent opponents to racial equality. Oftentimes they’re a complicated mixture of both opposition and service.

“We need to be very honest. It’s not that they understood the work and the importance of the community and saw Black people as equal,” Williams says. “Most of them hold racially derogatory attitudes about Black people. They see Black people as their moral, intellectual and social inferiors.”

Knowing that one’s fellow sisters view you as inferior and still deciding to take these sacred vows is a revolutionary act.

“We know that the denial of Black female virtue is the core tenant of white Christian supremacy,” Williams says. “And so we have to really think about what it means for Black women to dare to profess these sacred vows, especially the vow of celibacy in a society and church that deems all Black people and especially Black women and girls as sexually promiscuous.”

Not only does a life as a nun debunk notions of Black women’s sexual promiscuity, nuns are regarded as women worthy of respect and reverence.

“Nuns are brides of Christ,” Williams says. “They’re literally the spouse of Jesus Christ. So what would it mean for these women to do this in a church and a society that imagines Christ as white? And there are these Black brides. And they are deserving of protection.”

During the Jim Crow era, protection was needed. Black women were often relegated to the positions of teacher, nurse or domestic servitude. As one nun told Williams, “You know how we were being raped in those households.” The veil provided protection.

“What does it mean to say that nobody has a right to my body?” Williams asks. Dr. Theresa Perry, Professor of Africana Studies and Education at Simmons University, said of Black sisters and the vow of chastity, “Celibacy frees us to free others. Because we don’t have the responsibilities of motherhood, we can dedicate ourselves completely to the struggle.”

Williams says this was a radical notion when even Black liberation movements were telling Black women their primary role was to birth babies for the revolution.

Without the demands of motherhood and romantic partnerships, these sisters are able to become principals, hospital leaders, and professors. Williams suggests that the choice to be celibate places you at odds with some many segments of society.

“You are a threat,” she states. “You can’t be controlled. Your children can’t be threatened. The kinds of ways in which women can be controlled makes the sisters extremely dangerous.”

Williams says Black nuns are an important sect of Black feminism that has gone unexamined.

But while becoming a nun offered protection from some of the forces working against Black women, the racism within the church still proved detrimental. Williams found that many of the Black nuns she uncovered died young. “Many of their peers speculated that when those women decide to stay in religious life, in the faith, there was so much hostility that it cost them,” Williams says.

These sisters didn’t just face racism from their white faith communities, they were also met with the misogynoir from Black priests, brothers, and laymen. It was the sexism that made Sister M. Gray leave the sisterhood. She was the only woman at the Black Catholic Clergy Caucus and the Black men there were not welcoming. They surrounded her and screamed in her face for 30 minutes, demanding that she leave. Somehow, she found the courage to stand her ground.

“You can’t understand why [Black nuns] are at the vanguard without understanding their history,” Williams says. “Long before there were Black priests in this country, there were Black sisters. Black sisters’ successes made these men possible. They saw it as betrayal because these women fought for you and then you did…that.”

Despite the racism and the sexism, many of the new sisters serving as nuns are African women.

“We know that women’s religious life begins in Africa,” Williams says. “The future face of the Catholic sister is going to be brown and most likely African.” If the face of nuns across the world are Black women, Williams says that means people all over the world need to know the stories of Black nuns.

Subversive Habits is available now.