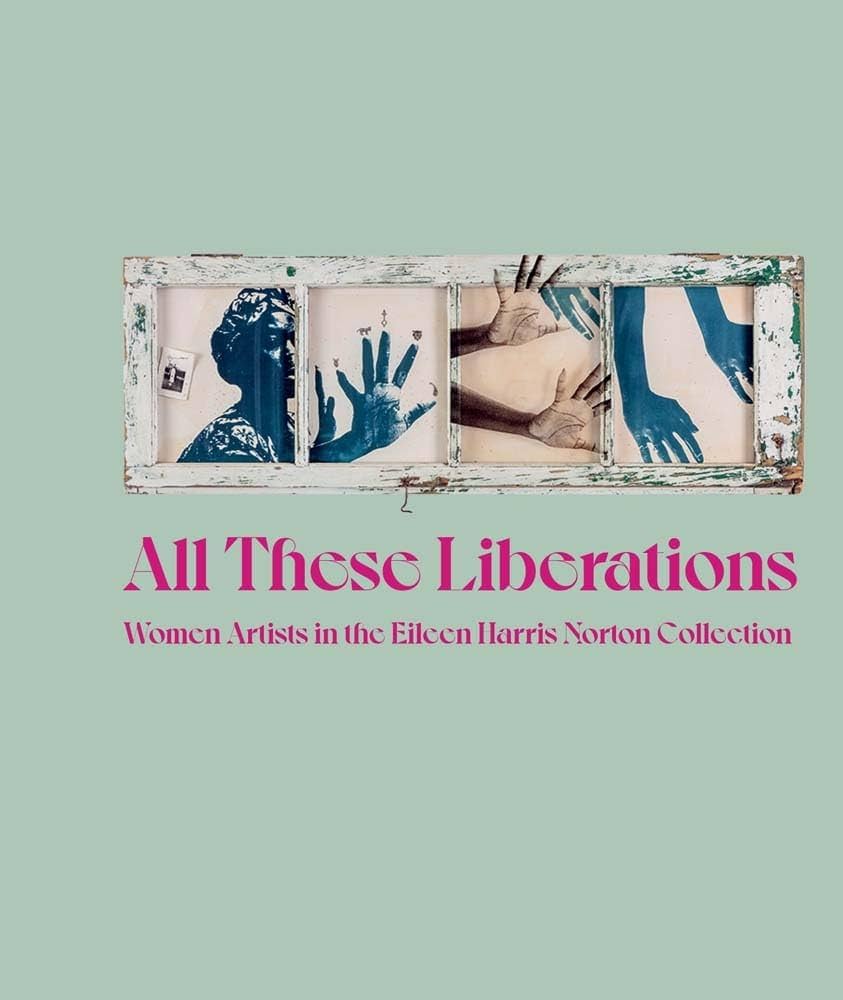

Eileen Harris Norton has long been an advocate for underrepresented artists. As an integral part of the Los Angeles arts scene—and the Black arts scene in general—she helped build the careers of artists and curators like Thelma Golden, Mark Bradford, and Lorna Simpson. Now, her work and contributions will be explored in the new book, All These Liberations: Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection.

Distributed by Yale University Press and edited by California African American Museum curator Taylor Renee Aldridge, All These Liberations will highlight Harris Norton’s advocacy for marginalized artists, curators, and more through her work and philanthropy. Eileen’s efforts have continued throughout the years, particularly in her co-founding of Art + Practice, a direct response to the homeless youth crisis in LA. By helping to shape the careers of so many creatives, Norton has cemented a lasting legacy, and laid a foundation for emerging artists for years to come.

As the editor of the first book on the collection, Aldridge has crafted an impeccable scholarly resource and introduction to Eileen. Through conversations with Eileen and her esteemed friends, the decorated writer gradually uncovered more about Harris Norton’s long-standing influence. “Eileen has collected so many works, and made so many indelible impacts on the art ecosystem writ large,” Aldridge explains. “The challenge was knowing that the book would not be comprehensive. It’s my hope though, that All These Liberations will attract more scholars to engage with the collection and expand on the scholarship on works in the collection in coming years.”

Featuring art from Sadie Barnette, Carolyn Castaño, Sonya Clark, Genevieve Gaignard, Julie Mehretu, Senga Nengudi, Lorraine O’Grady, Calida Rawles, Alison Saar, Amy Sherald, Kara Walker, Carrie Mae Weems, and many others, All These Liberations gives readers a deeper look into Harris Norton’s impact, how she constructed her expansive collection, and her promote of Black artists through a practice spanning over fifty years.

ESSENCE: You edited All These Liberations: Women Artists in the Eileen Harris Norton Collection. Tell me, how did the opportunity first come to you?

Taylor Renee Aldridge: Shortly after I began working at the California African American Museum as a curator, Art + Practice and CAAM entered into an institutional partnership. Through this collaboration I met Eileen, and I learned that she and her collections manager were working on a book that celebrates the collection and needed an editor. I had recently published art catalogs for my exhibitions Enunciated Life and Mario Moore | Enshrined: Presence + Preservation. I was also working as co-editor for, ARTS.BLACK, a publication I co-founded ten years ago, which exclusively publishes writing by emerging Black critics from the global diaspora. The book was an opportunity to extend on this work and these networks I’ve been a part of for many years. Given Eileen’s generosity and unique taste as a collector and patron, I was really excited by the possibility to platform all of the work that she has done in four-plus decades. I pitched this idea to Yale to chart Eileen’s influence on the fabric of contemporary museum collections and the art ecosystem writ large. Her story and collection are just so robust, there’s so much to build upon and talk about.

There is so much dialogue now in the artworld about Black artists having a moment because they are being recognized by the mainstream, and their works are selling at price points that they have long deserved. But in recognizing that, we have to look at the people who cultivated the conditions for this to happen. Eileen is one of those pioneers who enabled the artworld we see today. After talking with Eileen’s close colleagues, Mark Bradford and Thelma Golden–who have been so illuminating for my research–I knew I needed to show that Eileen’s work of championing cutting-edge artists and curators early in their career, is why we have the more diverse, imaginative and equitable artworld we see today. This was such an inspiring task to execute.

What inspired the creation of this book? Why was 2024 the right time to publish it?

Although Eileen has been collecting work since the 1970’s, there has never been a book to document her collection and the impact of her patronage over many years. When we think about major contemporary art collecting, Black women are not as visible in that conversation. When I think about Eileen, I often think about another Black woman educator, collector and activist, Peggy Cooper Cafritz, and how she, too, expanded the realm of what collectors are expected to do. As she and Eileen have done, collectors can found educational centers, they can endow professorships, and widen access to art education and arts-making for historically marginalized groups. Peggy is no longer with us, but her impact continues to reverberate. We should be celebrating our Black women leaders and changemakers while they’re here, while we still have access to their wisdom and brilliance. Eileen’s story has always been urgent, and I’m glad that the right pieces finally fell in place so that this could happen. 2024 is a special year for many reasons, specifically because it’s the 10th anniversary of Art + Practice’s founding, a social service organization and art gallery co-founded by Eileen to serve LA youth and its immediate Leimert Park community.

In what ways has Eileen Harris Norton shaped the Los Angeles arts scene, and the Black arts scene in general?

When Eileen began collecting more frequently in the 1980’s with her then-husband Peter, her practice was very hands-on and pedestrian. A lot of burgeoning artists in LA at the time had studios in Venice, where she was living. So she would stumble upon artwork when artists would facilitate open studios and she started to understand artists’ environments; their needs and what enabled them to make. She and Peter started to offer grants to artists and curators who had not yet been fully recognized by the mainstream artworld. She also collected work that was nuanced and non-traditional, at a moment when artists began incorporating a wide variety of materials into their practice. These artists are considered canonical in contemporary art history—like David Hammons, Betye Saar and Senga Nengudi. She’s, in part, responsible for the visibility of so many artists of color, as well as the curators who have championed them, namely curators and scholars like Kellie Jones, Thelma Golden, and Susan Cahan who have gone on to expand scholarship on the history of Black arts in Los Angeles and beyond. Jones, Cahan and Golden are also contributors to All These Liberations, so I was really excited by the opportunity to tell her story through their lens, and show how fundamental she’s been to the art industry we see today.

Eileen has been such a quiet force for so long. Her patronage grew alongside the development of the L.A arts institutional community. She made a variety of gifts to major museums in the city over the years, and more recently, she gave a large gift to support an endowed Faculty Chair position at CalArts, named for renowned Los Angeles artist and educator, Charles Gaines. Eileen understands how impactful holistic support can be in instituting change and specifically cultivating more opportunities for people of color, who wish to grow in this industry.

Following Lorna Simpson’s foreword, you opened All These Liberations with words from Dionne Brand and Audre Lorde. Why did you choose these particular words? How do these quotes speak to the overall theme of the book?

I really appreciate this question. Given that the focus of the book is on women artists of color, Black feminist thought was a toolbox I pulled from a lot in making All These LIberations. The artists are transnational and from the global majority, so I kept thinking through the feminist organizing work that people like Lorde and Brand carried out in the time Eileen was collecting, and how their activism and poetry is a great mirror for the socio-political themes that are recurring in the collection. Audre Lorde’s poem, Who Said it Was Simple is what the book’s title derives from, and addresses how early feminism and Black power movements were not considerate or inclusive of Black women. The Brand epigraph comes from her book The Blue Clerk, where she says: “Modernity can spread a bed of weaponry to what it calls the far reaches of the globe but it cannot spread women’s equality. It cannot stem the liquidity of capital, it cannot even feed its own populations but female bodies are still trophy to tradition and culture.”

These two poems really characterize the women artists in Eileen’s collection and how so many of them critiqued our modern cultures of patriarchy and centered their own concerns. The works tend to be self-referential, sharing personal experiences that exemplify broader experiences of women during that time. I am thinking about the 1970s work of Senga Nengudi in the collection which engages with these malleable forms to elicit the body, I am thinking of Ana Mendieta who made these impressions of her body on different landscapes throughout the world to remark about memory, loss, and impermanence, shortly before she was allegedly murdered by her husband, infamous white male artist, Carl Andre. Black women artists Ruth Waddy and Samella Lewis were making work while actively establishing a Black arts ecosystem here in L.A during the 60s, 70s and 80s.

In making the book, I kept thinking about what was happening in the world at that time since Eileen collected her first Waddy piece in 1976; globalization, multiculturalism, and Black feminism emerged within those decades. These socio-political currents are naturally present in the works Eileen collected and the poems helped me to set the tone for the book to address all of this.

This book not only highlights Eileen Harris Norton as an art collector, but also her contributions to the art world. For those who aren’t familiar with Eileen, what is it that you hope readers will take from the book?

I hope that it demystifies the work we do in the artworld more broadly. So much of this work is invisible, and happens privately. In reading Eileen’s story and the ways in which she has collected artworks intuitively, and found ways to support not only artists, but curators and educators in the field, I hope readers understand that there is an ecosystem that enables art making and exhibiting—not just transactional markets. There are so many ways that collectors can support and help advance the careers of people working in this ecosystem to encourage a more diverse and accessible artworld. As a former teacher herself, Eileen knows how education, and art education in particular, can allow people to think critically, develop imagination, and provide creative solutions for our ever-changing world. I hope readers take note from Eileen and think about ways they can encourage education and positive change, even in small ways.

The words and works of several artists appear in this book. With you being a curator at the California African American Museum, did you take a curatorial approach when putting the book together? Can you walk me through that process?

I think of art curation as writing an essay through objects. The work of curating, writing and editing all require similar approaches of deep thought, and workshopping ideas, sometimes consulting with thought-partners around an idea. One of the earlier titles I worked with for the book was Rootstock, which is part of a plant, often an underground part, from which new above-ground growth can be produced. I thought it was a perfect metaphor for the work Eileen does, and although we went with a different title, the term became a guiding principle for how I wanted to articulate Eileen’s narrative and the artworks in her collection. Eileen’s quiet support underground, enabled fruitful products of a robust ecosystem for us all to witness and benefit from.

Essays by the brilliant Sarah Elizabeth Lewis and Steven Nelson had already been collected, and the interview between Eileen and Thelma had been recorded, prior to my involvement. So I had a generous foundation to work from. I thought that so many works in the collection were in dialogue with one another like a web of roots belonging to a plant, and so I wanted to engage fresh voices to talk about multiple works in each essay. For instance, I had been following the work of Genevieve Hycinthe for some time, and I thought the way that she wrote about Ana Mendieta’s work in the lexicon of African spirituality was so expansive and robust. She pitched this lovely abstract to write about some artists in the collection who were engaging with abstraction, performance and the metaphysical, such as Xiomara De Oliver, Adrian Piper and Alma Thomas. Similarly, I have known and appreciated, for some time, Gelare Khoshgozaran’s work as an artist and writer, who focuses on themes of exile and belonging; I knew their perspective on the work of Mona Hatoum, Doris Salcedo and Samira Yamin would be generative and rigorous. I could have invited dozens of writers to write plates for each work in the collection, but in my gut, I felt that the works would be better served in this more dialogical approach.

For you, what was the most challenging part of editing All These Liberations? What obstacles did you have to overcome?

Eileen has collected so many works, and made so many indelible impacts on the art ecosystem writ large. The challenge was knowing that the book would not be comprehensive. It’s my hope though, that All These Liberations will attract more scholars to engage with the collection and expand on the scholarship on works in the collection in coming years.

What does Eileen Harris Norton mean to you?

Eileen means so much to me as a curator and writer. My interest in artworld discourse and living artists began with the Black postmodernists in the collection like Lorna Simpson, Wangechi Mutu, Carrie Mae Weems. They were pioneering in the ways they used form and visual language to remark about lived experience; gender, sex, politics. And Thelma Golden, who is in part responsible for advancing the careers of such artists has been, through this trickle-down effect, foundational to my own work as a curator. To learn that Eileen supported these artists early on in their careers, and specifically championed Thelma’s career, whose work birthed a whole generation of Black young scholars like myself, is a prime example of what art patronage can do. It can build worlds, sustain careers and shift a vanguard forward into the mainstream. Working with Eileen and stewarding this urgent book endeavor into the world is such a full-circle moment.