This story originally appeared in July/August 2024 issue of ESSENCE magazine, on newsstands July 25.

The Fourth of July weekend in New Orleans holds a special significance, not just for locals but for music enthusiasts and aficionados of Black culture worldwide. It’s a time when the Big Easy becomes a nexus of Blackness—the city is buzzing with fans, socialites, celebrities and artists who’ve journeyed to the birthplace of jazz for one reason: to revel in the ESSENCE Festival of Culture.

Hosted within the symbolic embrace of the Deep South, the ESSENCE Festival takes on a character all its own—having found its natural home in New Orleans, a hotbed of Black music and heritage. More than just a backdrop for the festivities, the city becomes an indispensable element that defines the festival itself. It’s a true sanctuary for Black music.

While the pages of the magazine serve as a platform to amplify Black women’s voices, ESSENCE Fest went a step further, carving out a space for the expression of Black artistry. It was a brilliant move, in part because it addressed a void: America’s overt racism made celebrating Black music on such a broad scale nearly impossible. In the 1980s, for example, MTV faced backlash for its neglect of Black artists, including its refusal to air Rick James’s “Super Freak.” Before Michael Jackson’s “Billie Jean” video, Black artists rarely appeared on MTV. Jackson’s immense popularity, and the pressure from CBS, eventually led MTV to air “Billie Jean” in 1983—which helped break the color barrier on the network. In a landscape where Black music and culture were often overlooked by mainstream media and music festivals, ESSENCE Fest was unwavering in its focus on uplifting Black people.

By the mid-1990s, ESSENCE cofounder Ed Lewis was galvanized by the magazine’s success, which birthed a vision that transcended the pages of the publication. The festival began as an extension of the magazine, to commemorate its 25th anniversary in 1995; it has since evolved into a global phenomenon. Lewis and his team spared no expense back then, lauding the magazine’s quarter century of existence with a celebration that surpassed all expectations.

“I wanted to do something a little bit different, instead of just having a big party here in New York and thanking everyone,” Lewis explained, reflecting on the genesis of the festival in the OWN Time of Essence documentary, which traces the history of the brand. “[The jazz promoter] George Wein said to me, ‘Ed, have you ever thought about doing a music festival in New Orleans over the Fourth of July weekend at the Superdome? No one comes to New Orleans over the Fourth of July weekend, unless there’s a real reason.’ And I said, Oh my God, he may be on to something.” That conversation planted the seeds of a cultural movement. It gave rise to the annual ESSENCE Music Festival, which blossomed into a worldwide celebration of Black culture.

When it comes to programming, as each day’s lively atmosphere shifts into night, musical performances take center stage, where the sound isn’t just heard but deeply felt. The thoughtfully curated lineups span a wide spectrum of genres—speaking to the notion that all music inherently embodies elements of Black culture, and making the festival a platform for the diversity of Black musical expression.

“I think we’ve always tried to find ways to incorporate the different genres of music that were birthed out of New Orleans,” explains Hakeem Holmes, Vice President of what is now called the ESSENCE Festival of Culture. A NOLA native, Holmes joined the festival team as an intern in 2013 and has witnessed the growth and evolution of the event. “So there’s jazz, we leaned a lot into gospel, and then, in terms of Mardi Gras—Indian music, bounce music—these are genres that don’t have as much visibility, or weren’t given stadium opportunities. I think that, too, is essential to the experience of the ESSENCE Festival.”

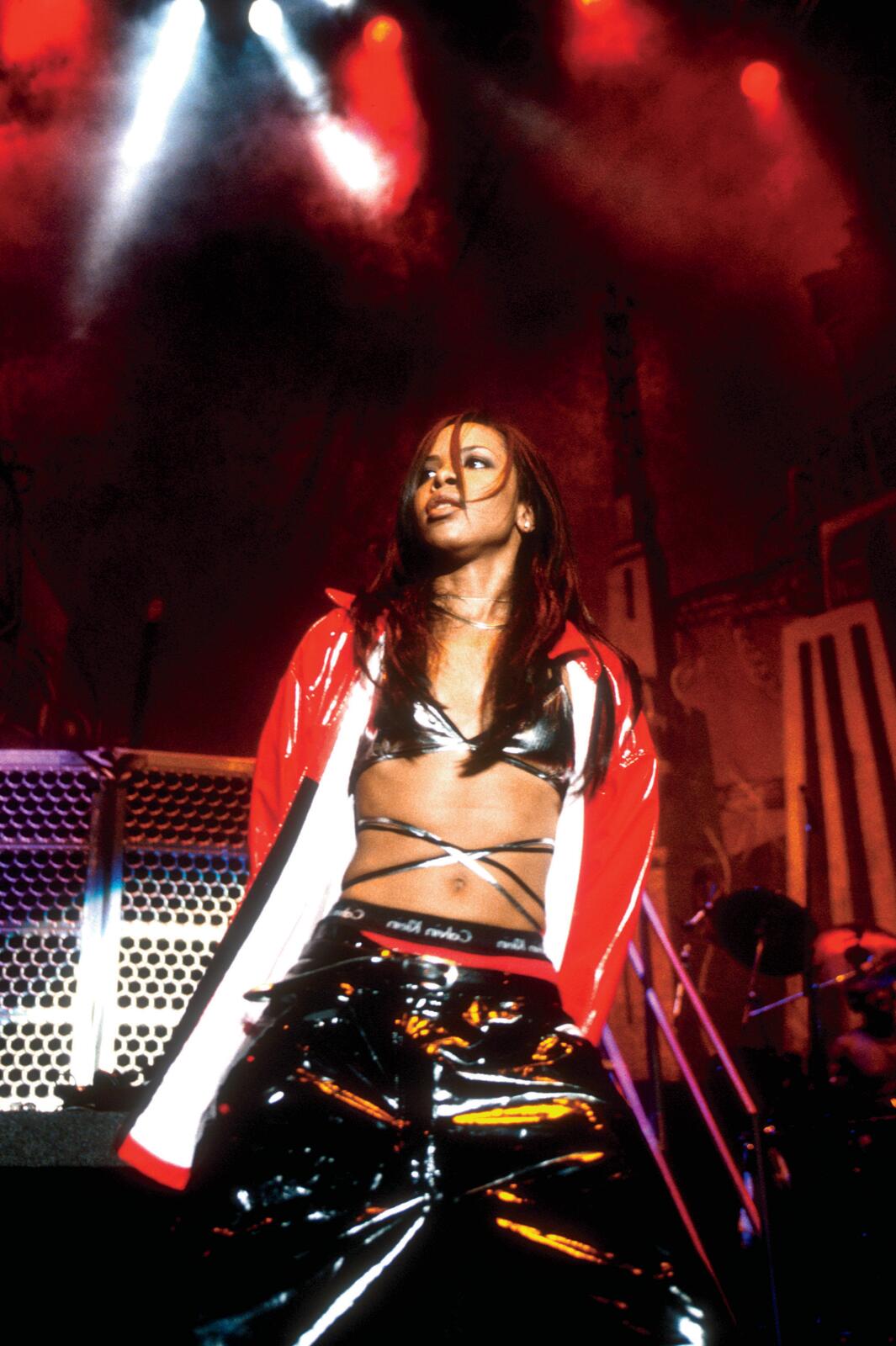

In 1995, the festival’s inaugural year, the landscape of music was changing right before our eyes, with a wealth of Black acts in the pipeline. Pop darlings Mariah Carey, Whitney Houston and Tina Turner had all released projects within the decade, while the younger generation, which included Brandy, Monica and Usher, was just entering the scene. The festival’s first lineup was indicative of the time, with a billing that included artists like Patti LaBelle, Aaliyah, the Treme Brass Band and the Ohio Players, to name a few. These stars set a precedent for the caliber of talent that would come to define the yearly festival.

James “Diamond” Williams, the drummer of the funk ensemble Ohio Players, highlighted how the festival showcased the diverse range of Black music and its widespread appeal across the country. “In 1988 or ’89, we had released a new album on Track Records,” Williams says. “So at ESSENCE Festival, in 1995, this band brought funk. We were forefathers of that institution, of that musical talent, and we’re quite proud of that. We wrote two platinum albums in one year, a feat that I think has yet to be achieved since then.”

Meanwhile, in 1994, Miss Patti had released Gems, adding another smash hit to her discography. Her song “Right Kind of Lover” peaked at No. 8 on the Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs chart and spent 25 weeks there—a precursor of what was to come at the first festival. Likewise, Aaliyah, who made waves with her 1994 debut album, Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number, took a bow on the festival main stage, captivating the audience with hits like “Back & Forth,” which reached No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 on July 2, 1994—precisely one year to the day before her festival performance.

The festival had its finger on the pulse of the culture, and it showed in the years that followed. In 1997, one of the featured acts was Kirk Franklin, who at the time was flipping traditional gospel music on its head with his secular, revolutionary sound on God’s Property from Kirk Franklin’s Nu Nation. Franklin’s groundbreaking tracks, like “Stomp,” set the stage on fire with their infectious beats, and that helped to propel his message to a larger audience. This was particularly important at a time when the gospel community was wary of his unorthodox style. “That was a God’s Property performance,” says Franklin of his first appearance at the festival. “We were all nervous, because it’s gospel music on the main stage, and that was very different.”

“Everybody had an agenda to really present their best, because that’s what ESSENCE had become known for.”

-Kirk Franklin

On the music-festival circuit, no matter how big artists became, there was a common destination: ESSENCE Fest. It served as an obligatory venue for Black stars to perform. “Whether you are performing or somebody else is performing, it meant something just to be in the room, to be able to watch people, especially entertainers that look like you and that always came with their A game,” Franklin explains. “That’s what ESSENCE was—that was the standard. Even though it was an unspoken standard, you always knew you had to come with your A game, because of the environment and the ecosystem that you were walking into when it comes to talent. Nobody was coming in off the cuff or just comfortable. Everybody had an agenda to present their best, because that’s what ESSENCE had become known for when it came to Black presentation.”

Williams shares a similar sentiment. “Performing meant that we were playing among the best, and it was a weekend that everybody wanted to go to. Ego was hall-to-hall, wall-to-wall. ESSENCE Festival was the place to be—the city was there, and you just wanted to be there.”

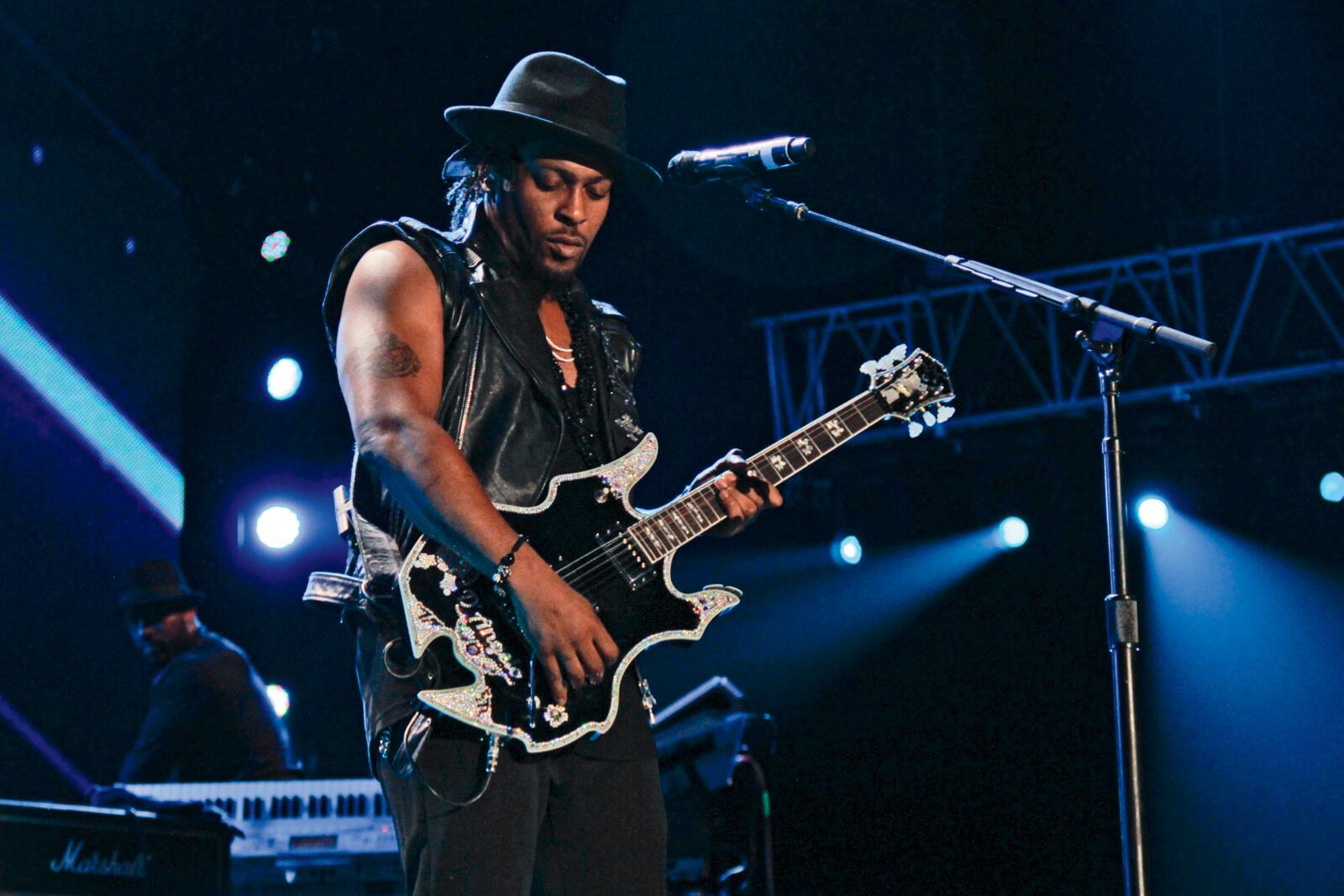

The new millennium saw a variety of up-and-comers added to the fold. There was a young Destiny’s Child performing in 2001, fresh off the release of Survivor. R&B duo Kenny Lattimore and Chanté Moore performed hits from their duet album Things That Lovers Do in 2004; and in 2008, Jill Scott, who had already released her trio of critically acclaimed albums—Who Is Jill Scott, Beautifully Human and The Real Thing—hit the stage. Scott was a welcome addition to the bubbling neosoul movement led by artists D’Angelo and Erykah Badu, both of whom graced the festival stage multiple times. The venue was the antithesis of the opulence of hip-hop’s “shiny suit” era of the early 2000s, embodying a more eclectic and soulful aesthetic.

“We’re standing 10 toes down, that we as a culture, and as a people, are not a monolith,” says Holmes. “There is something for everyone. All of those things are coming to life, to invite everybody and allow everyone to see themselves as a part of it.”

While main-stage acts have been known to put on a show, the other venues and the super lounges turned the spotlight on artists you may not have known before. “We’re creating an opportunity for people to come in and be on the big stage—or in the super lounges,” Holmes continues. “These spaces were where we got more acquainted with alternative-rap groups like De La Soul, rising R&B stars Melanie Fiona and Miguel, and iconic collectives like Soul Rebels Brass Band and George Clinton & Parliament.”

In the mid-2000s, a rising titan of rap emerged in the form of Kanye West. By 2005 he was coasting on the success of his debut album, The College Dropout, propelled by his hit “Jesus Walks.”

“That performance was pretty incredible when I did see it live,” recalls Gina Charbonnet, the principal owner of the events company GeChar, Inc., and executive producer for the festival. “I think we can say that he’s a prolific writer, and he might have been one of the first hip-hop artists ESSENCE had onstage.”

West performed in the ESSENCE arena in 2005, a month before Hurricane Katrina ravaged New Orleans. He returned to perform in 2008—following his famous political outcry on national television in the aftermath of the tragic natural disaster, when he stated, “George Bush doesn’t care about Black people.” Even during the turmoil that Katrina left in its wake, the festival pressed on; the event was temporarily moved to Houston in 2006.

Despite that pivot, from the festival’s inception in 1995 through 2010, Maze featuring Frankie Beverly remained a mainstay, closing out the show each year. They had an undeniable impact on the audience; concertgoers clad in white linen swayed to hits like “We Are One” and “Happy Feelin’s,” and others exuberantly joined in the electric slide in the aisles. Such timeless cult classics spoke directly to the Black consciousness, in a way that made you want to experience both joy and pain. “The dome was packed,” Charbonnet says. “People didn’t leave until 2:30 a.m.”

In the balancing act of showcasing both seasoned and neophyte performers, the festival’s commitment to honoring Black music legends has ensured that the contributions of our pioneers are lifted up. Prince delivered arguably the most unforgettable performance to date, in 2014. “You just had to be in the room,” Holmes notes. “Everybody was in their white, their purple, their psychedelic tie-dye. You just knew that you were going to a Prince show. There wasn’t this call to action, like ‘Wear this color.’ Everybody, just us as a people, we were wearing something purple. And then, it being one of his last performances makes it all the more special as a memory.”

Those were the sorts of nuances that the festival offered, as a uniquely Black space—experiences you simply couldn’t get anywhere else. There’s an unmistakable ancestral atmosphere to the rousing three-day celebration, akin to the warmth of a family reunion. Holmes bore witness to it in 2018, when Janet Jackson went on with the show just days after her father’s passing. “A week or so later, she performed—and everyone thought that she wasn’t going to, because this was a sensitive time for her and her family,” Holmes explains. “Those are the moments—when you talk about joy and empathy, what you want to take away from a festival is that. And these artists know that they can share that with this audience.”

Charbonnet agrees that the music at the festival “kind of soothes us, in a way that can take our mind off something or help us recall this memory. That’s the one thing I think music does—it sort of bridges this gap for us. It breaks down a lot of barriers, too. The music speaks to our brains in a different way. I think it really has this vibration—that it connects with us, I think on many different levels. And I think we do need that kind of connection, to keep us together as people, so that we can continue to tell our stories and to talk to each other and to heal.”

The ESSENCE Festival is a time of jubilation, inspiration and connection. It’s also a celebration of Black music and culture that continues to shape and redefine the cultural landscape—not just of New Orleans, but of the world at large. Each year, it reaffirms the richness of our heritage and the limitless potential of our future. Now, as the festival prepares to mark three decades of existence, we’re not merely celebrating the time passed—we’re highlighting its profound impact in shaping the expansiveness of Black creativity. By providing a premier platform for both legendary and emerging Black musicians, the festival has significantly influenced the trajectory of Black music and culture, helping to preserve its roots while nurturing its evolution.