There’s a story often told about Arthur McGee, a designer whose work in the 1960s-1990s earned him titles like the “Grandfather of Designers of Color” and “Dean of African American Designers.” It’s one that McGee himself told: as a young student, eager to learn about the industry, McGee spent six months at the Fashion Institute of Technology studying apparel design and millinery. There he met contemporaries like Charles James, who would go on to become a legendary name in American fashion. But after that short stint, he left the school. “I quit [FIT] because they said to me, ‘There’s no jobs for a Black designer,” McGee, who would go on to become a mentor to designers like Willi Smith, Stephen Burrows, B. Michael, and more, told the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a video being made to canonize his contributions to the industry. “So I left.”

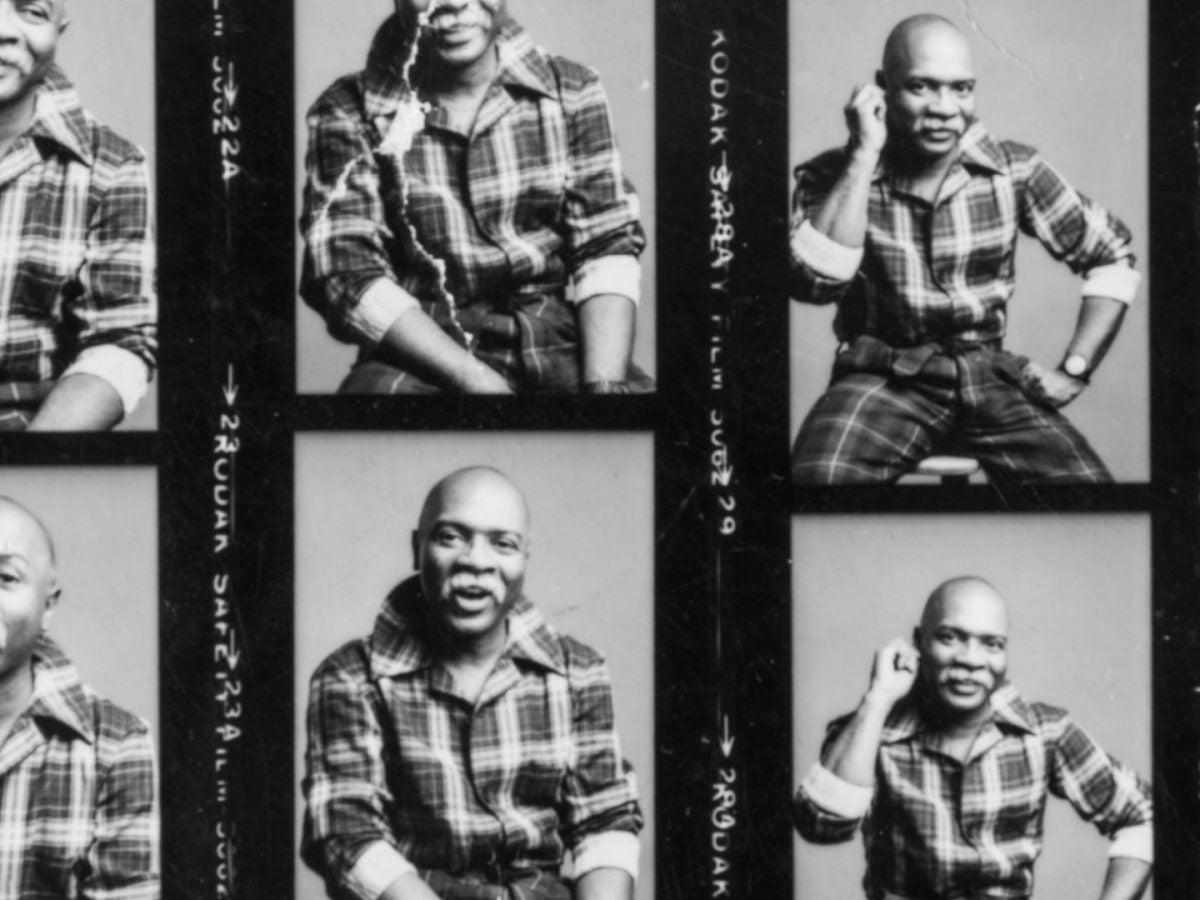

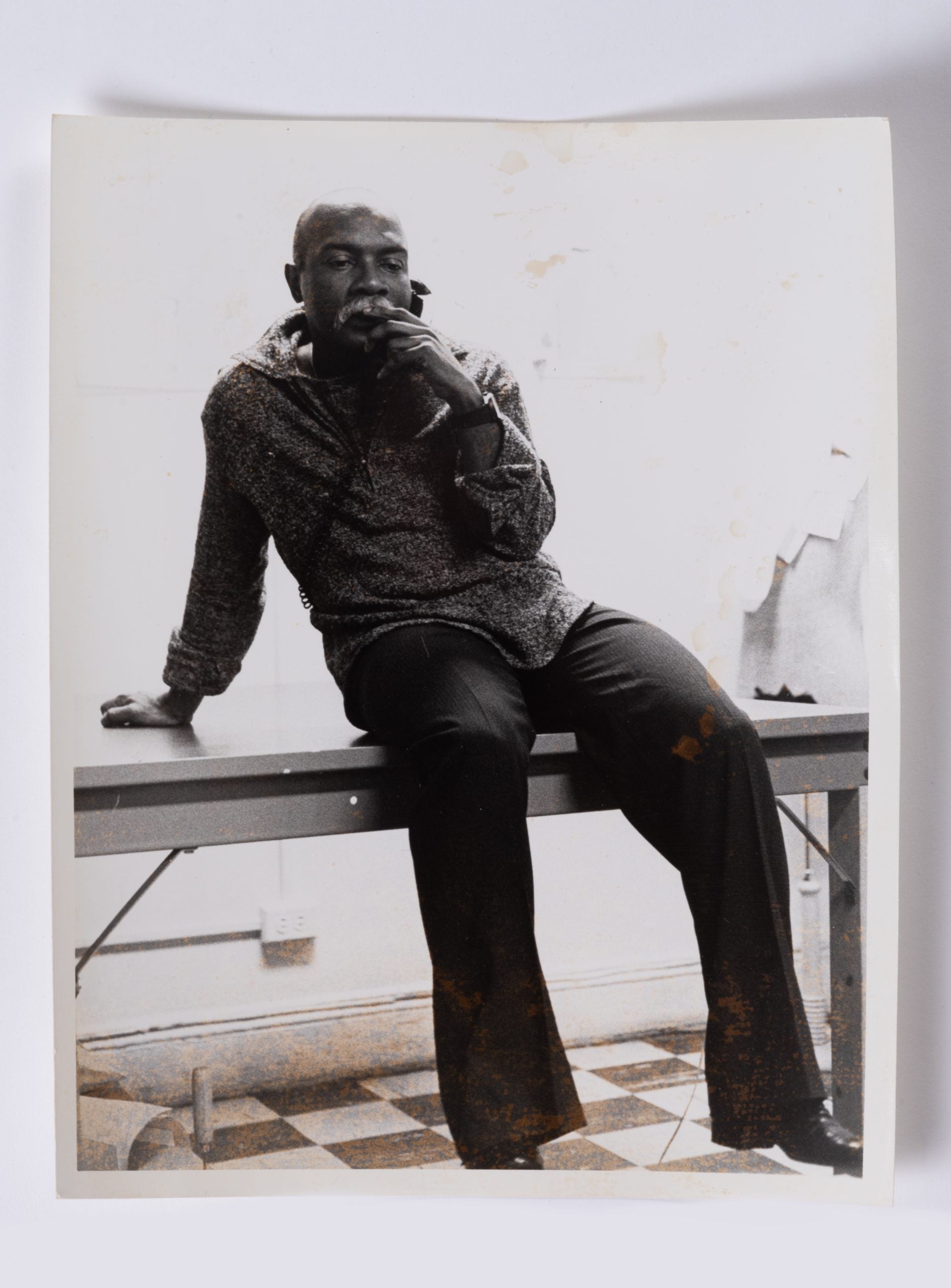

It’s an interesting story about the designer whose archive will hit the auction block at Hindman in a collection of 45 garments on March 14. According to a press release, “In addition to the 45 ensembles in this sale that were created by Arthur McGee between the 1970s and the 1990s, the sale also includes McGee’s archive, with design sketches and inspiration, hundreds of photographs from throughout McGee’s career.”

For many, it’s a tale that shows all of the resistance McGee — and other Black designers of the time — was up against. But it also provides insight into the designer’s character: a headstrong creative who would work on his own terms and time rather than fighting for a seat at a table where he wasn’t welcome.

“He was very independent, and he did what he wanted to do,” Maxine Gordon, a former client and close friend of McGee’s, tells ESSENCE. Gordon and Johnetta Shearer, another former client, have launched a scholarship for emerging designers in McGee’s name to continue his legacy. “He followed his own genius.”

Born in 1933, Arthur McGee got his love of fashion from his dressmaking mother. In fact, her sensibilities influenced his trajectory: because his mother had an affinity for hats, McGee picked up millinery, which he would go on to study, first in New York at Traphagen School of Design, where he enrolled on scholarship after winning a contest, and then at FIT. After meeting James at FIT, he went on to work for the designer but also took on commissions on his own, developing a clientele from Broadway, including names like Sybil Burton and Josephine Purmice.

In 1957 McGee made history. At 24, he became the first known Black designer to run an established design studio on Seventh Avenue in the garment district, then at Bobbie Brooks. And though he wasn’t always given the respect he deserved, with fabric store owners walking past him in search of the designers, he worked diligently, making his way through various brands and companies. (In another anecdote, McGee once told the story of a boss who often complained that he wanted the designer to create something “new,” so he turned in a sweater with three sleeves to make a point.) He even got pieces under his own name placed in stores like Henri Bendel, Bloomingdale’s, Bergdorf Goodman, and Saks Fifth Avenue. “Imagine an engine of a machine, and there are many parts that are needed in order for it to run successfully,” Timothy Long, Hindman’s Couture and Luxury Accessories Director and Senior Specialist, says. McGee was an integral part of the industry’s machine during his time.

Gordon first met McGee after wandering into his shop on St. Mark’s Place in New York. At the time, he was designing his own line out of the space catering to a group of clients. As was common with designers, particularly Black designers, he ran a popular customs business. He wasn’t designing for an amorphous “Arthur McGee woman,” as designers might say today. No, McGee knew the names of the women who bought his clothes. He knew their sizes, tastes, and needs and designed them accordingly.

“I remember walking by and seeing a drop waist cotton dress, and I went in and asked was it for sale,” Gordon recalls. “He said, ‘oh yeah, that would look good on you. Try it on.’ And he brought out some other stuff he thought would look good on me.

“Once you wore his clothes, that was it. You couldn’t wear anyone else.” In addition to dressing the likes of the Negro Ensemble Company and Dance Theater of Harlem, McGee dressed Cicely Tyson, Stevie Wonder, Phyllis Hyman, Lena Horne, Miles Davis, Maxine’s husband Dexter Gordon, and more. His designs graced not only the streets of New York and Miami, where he moved to and opened a shop for a time but also famed red carpets like the Academy Awards.

“He was famous in a circle of Black designers and Black artists,” Johnetta Shearer says. She met McGee in 1974 at a fashion show in Miami where [Phyllis] Hyman was performing. “Arthur had done the clothes,” she recalls of her first exposure. The designer was operating out of a shop on Miracle Mile in Coral Gables but eventually moved to Biscayne Boulevard before going back to New York City. “They were gorgeous, and I became a client.”

When some look back at McGee’s business today, they call it underappreciated or underrated. And while it is true that institutional racism stood in his way, McGee’s business was also one of his own choices. His workshop at 10th street and Broadway became an open door for designers of color who would come in to ask McGee questions or learn a draping technique or get advice on the industry. And while some of them went on to build sizeable operations, McGee chose something else.

As much as he was a teacher of design (in addition to the informal lessons he gave designers at his studio, he traveled to China and South Africa to teach), McGee was a student of it. He studied the designs of Issey Miyake, whom he was particularly inspired by, and also books on origami, experimenting with working those techniques into his process. He would spend hours with clients shopping for fabrics and studying books on Madame Vionnet, dyeing textiles, and standard patternmaking.

The result means McGee’s output had a range, unlike most designers, partially possible by his insistence on a more personal approach to the business. From a Zulu blanket coat to white cotton shirt dresses and shirts with kimono sleeves that used African scarves as fabric to pearl embroidered coats fit for an Oscars appearance, McGee could do and did it all. He existed as a critical link in the canon of Black fashion designers — helping to pave the way and mentor the likes of Willi Smith, credited by many as the inventor of streetwear, and Ed Austin, who became the first Black designer with a couture atelier on Madison Avenue in 1975 with Austin Zuur — setting some of the groundwork that designers are still building on today.

McGee’s output was halted when he suffered a brain aneurysm and was put into a home. In the years to follow, honors rolled in from the Met as well as New York City and even the state of New York. In 2019 at the age of 86, McGee died, survived only by a brother.

“It’s important that he’s not forgotten,” Gordon says. “He wanted to make sure that he wasn’t forgotten. He would tell me and Johnetta that he didn’t do all of this work just for them to walk all over it.” And he did it on his own terms.

The auction goes live on March 14th at 11:00 am ET. Visit here for more info.