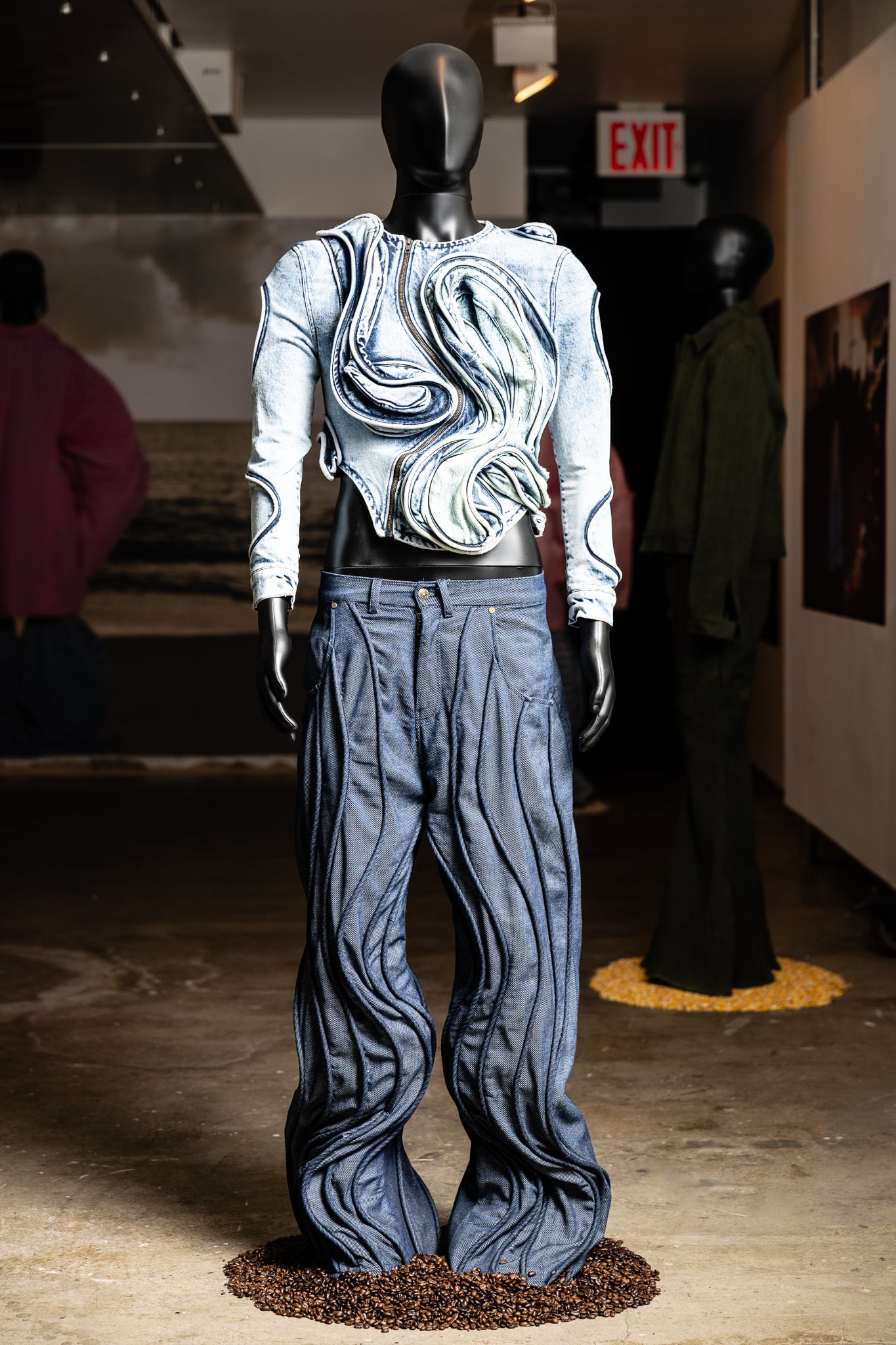

In Downtown Brooklyn at the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts on Thursday evening, Haiti’s bustling and vibrant community was pulsating throughout the interior of the lauded space. It was the opening evening for a new fashion exhibition entitled “Ti Maché,” which translates in English to “little walk” but really means “marketplace.” Daveed Baptiste, a skilled photographer, decided to dedicate the exhibit to his family’s migration to America in 2004. But, also he keys in on elements of Haitian culture which is seen in the clothing displayed throughout MoCADA. Beneath each mannequin wearing Baptiste’s unique pieces were piles of rice, coffee beans, corn, cotton, and other goods that represent the “marketplace” of Baptiste’s designs. He tells me that he wanted to expand his artistic capabilities through this special exhibit.

Baptiste arrived at his opening late wearing his own design, a red and white distorted plaid pant set, and was met with an immediate outpour of love from his community. This pattern was seen on one of the displays but instead, it appeared as a short sleeve top. Another exceptional look consisted of a deep blue jacket and pants with a squiggle zipper detail. The look that was featured on the flyer for the event was a sight to see in person. The baby pink plissé top up close was stunning; it featured rounded exaggerated sleeves. It was displayed with a pair of blue striped pants with a cinched detail right above the hem creating a slight tiered effect.

On how the curated evening came to be Amy Andrieux, chief curator at MoCADA shared she and Baptiste connected due to the time they spent separately at The New School’s Parsons School of Design. “Though he wasn’t my student, people suggested that we connect because we’re both Haitian and have [a large] love for art and fashion,” Andrieux said. Before meeting in person at an artist talk mutual friends urged them to join forces in some capacity. Once they did, she says it felt like kismet.

Andrieux expresses that at MoCADA there is a significant level of detail that correlates with the pride the staff there has for celebrating creatives across the African diaspora. She says that often means uplifting artists whilst they are shaping their first body of work. “With Daveed, it was a beautiful dance that explored our shared [Haitian] identity,” Andrieux said. “[He also explored] what it means to be Haitian and American at a time when reclamation of our history, our land, and our culture [determines] our collective future.” She goes on to describe how Baptiste’s exhibit provides an opportunity to create a dialogue about the depletion of “Haiti’s natural resources,” the “exploitation of migrants” and the displacement of Little Haiti’s community in Florida. “Daveed’s work and his show say it all: fast fashion is dead, wearable art is everything,” she adds.

“So many of my friends who are emerging designers have helped me in the [design] process,” Baptiste tells me. These friends include Shanel Campbell of Bed On Water, Matthew Valdez of Yatusabe, and Aaron Cooper from Blueprint Production. The photographer also expresses that he worked with Black queer production studio MASISI for the exhibition’s fashion film. The film and stills were shot by Jordan Blake who accompanied Baptiste in Miami’s “Little Haiti” which is also the latter’s hometown. Casting was executed by Akia Dorsainvil.

Blake shares that the energy in Miami could be described as immaculate. He particularly enjoyed the third day of shooting. “I’m grateful to have shot with Daveed and [to] to see it [all] come into fruition,” he said. Dorsainvil mentions that working with other Black creatives felt gratifying. “We were able to really amplify the beauty that [comes with] being Haitian, especially from the context of ‘Little Haiti’ in Miami,” they added.

On design inspirations, Baptiste says that he was looking at visual details that exist within Black communities. The texture of hair and braiding patterns were significant sources of inspiration. He says he even was energized by the curves that are on one’s head when they get braids. “I was also looking at the church hats that the woman and my church would wear and how those hats literally defy gravity,” Baptiste said. “They bend and [there’s] something very futuristic about them [to me].”

Baptiste sees Haitian artists as the future. Another aspect of the exhibition that was significant included three bags of money that were on display. This represented the role that Baptiste feels American dollars have had a hand in the destruction of Haiti and a double entendre of abundance–it also symbolizes the fight for freedom that Haitian and Haitian-Americans have been through over multiple generations socioeconomically. “Haitian people, we are revolutionary people,” Baptiste said. “Haiti became the first free Black Republic in the world and the first independent country in the Caribbean.” That is the context that Baptiste makes art from—a revolutionary point of view, dedicated to his ancestry.

“Ti Maché” is on view until December 3 at the MoCADA Museum.