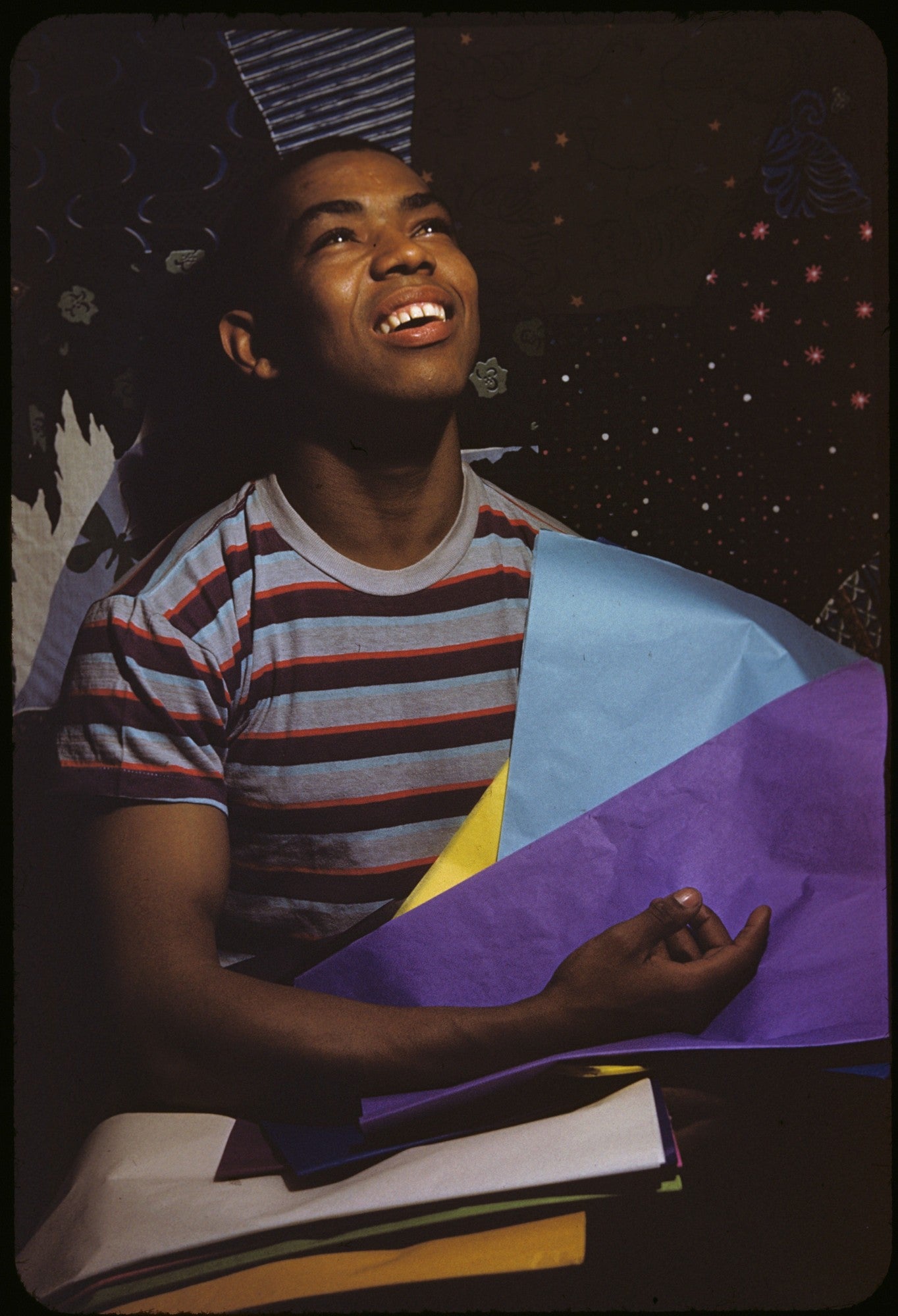

How much is Alvin Ailey owed? This pressing question lies at the heart of the Whitney Museum of Art’s latest exhibition, Edges of Ailey. Curated by the museum’s senior curator Adrienne Edwards and presented in partnership with the Alvin Ailey Dance Company, the exhibit delves into the boundless creativity of Ailey’s legendary life. Nearly seven years in the making, Edwards says she decided not only to engage with the sacred steps of the luminary but to peer intimately into the life of the man. Ailey once remarked, “I wanted to paint. I made watercolors. I wanted to sculpt. I wrote poetry. I wanted to write a great American novel.” Edwards uses this notion as a narrative frame to showcase a cultural custodian of unprecedented generosity.

Artworks are arranged thematically yet follow a loose chronology, reimagining the stunted standards of manipulated Southern history before strutting through practices of Black spirituality, migration, liberation, and love. From intimate letters, digitized recordings, poems, and archival footage, the show offers the most formative glimpse into Ailey’s inner life to date. Supported with over 80 all-star artists throughout history—Jean Michel-Basquiat, Kara Walker, Elizabeth Catlett, Mickalene Thomas, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and more—the exhibition utilizes Ailey’s spirit as a threshold to trek the evolution of Blackness through the performing art world. Edwards was struck most by Ailey’s acute sense of visuality.

“If you look at the posters in the show, the way he writes about dance, his choices of costume, lighting, he was constantly thinking about intentional image-making, which is why I think he referenced so much visual art, much like the way literature, too, feeds into the narrative aspects of dance-making,” Edwards noted.

The space, overwhelmingly rich and draped in the most delicious shade of red, evokes the grandeur of stage curtains, setting the scene for an overdue celebration of Ailey’s legacy. One of the most intriguing and subtle threads of the show was Ailey’s mastery of style. Throughout his career, he understood that costumes not only enhance the image-making aspect of dance but also ignite the audience’s imagination.

In “Revelations,” which flashes in segments on a multi-screen video installation drawn from archived recordings, he employed colors bold enough to resist life’s fatigue, with flowing silhouettes that mirrored the choreographer’s fluid movements. Examining the performance footage up close, alongside his scripts, one is struck by how much he related his art to cinema. The bejeweled bodices and dazzling headpieces in “For Bird—With Love” compete with Mickalene Thomas’s gold-kissed painting, as much a work of art as the dances themselves. “I love the sketches and images of the dancers performing at Studio 54 on opening night,” Edwards says as she highlights the kind of treasured tale so many of us didn’t know Ailey participated in.

One cannot help but marvel at the elegance embodied in the costumes—an elegance that feels both modern and eternal. There’s a glimpse of Cicely Tyson, a portrait of pastoral primness, dressed sharply in creamy white, gloves and hat included. In glimpses of “Cry,” Judith Jamison’s heavenly white shirt, simple and refined, stands as both a monument and testament to the richness of the adage “less is more.” These designs mimic the trend of ballet core that is steadily gaining traction, symbolic of how far Ailey’s work extends beyond the stage.

Why has it taken so long for Alvin Ailey to become globally synonymous with American history? Why isn’t his legacy as studiously regarded as others? The exhibition mends and repairs all historical oversights. “The archive is grief work. We lost a queer elder, we lost so many of those who came before us, especially in the context of art. But it is not about history; it’s about the future,” Edwards expresses. “It’s the leaving behind for us to follow, pick up, and carry to the next place.”

On opening night, surrounded by richly moisturized hues and thick perfumes, the atmosphere was swollen with what Ailey called “movements full of images.” A crowd full of all kinds of beauties, dressed in a myriad of ensembles fit for the stage of life: ballet flats, hair pulled back into tight, sleek buns, dresses so sumptuous and clinging, colored coats rinsed in the same shade of blood memory, all images that could trace their origins back to the edges of Ailey’s extensive intelligence and infinite imagination.

Edges of Ailey is not just an exhibition; it is a celebration of a living legacy. It also invites us to reflect on our memories and shared histories. Edwards ensures that visitors do not merely view Ailey’s work but drown in it, doused in the energy of every dance, every dream, and every discipline.

An expression of life itself, a testament to resilience, joy, and the human spirit’s indomitable will. The exhibition does more than honor Ailey, it challenges us to reconsider the very fabric of American cultural history, of American consciousness.

Edges of Ailey is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through February 9, 2025.

Lead Image Credit: Installation view of Edges of Ailey (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 25, 2024-February 9, 2025). From left to right: Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Fly Trap, 2024; Purvis Young, Love Dance, 1991. Photograph by Jason Lowrie/BFA.com. © BFA 2024