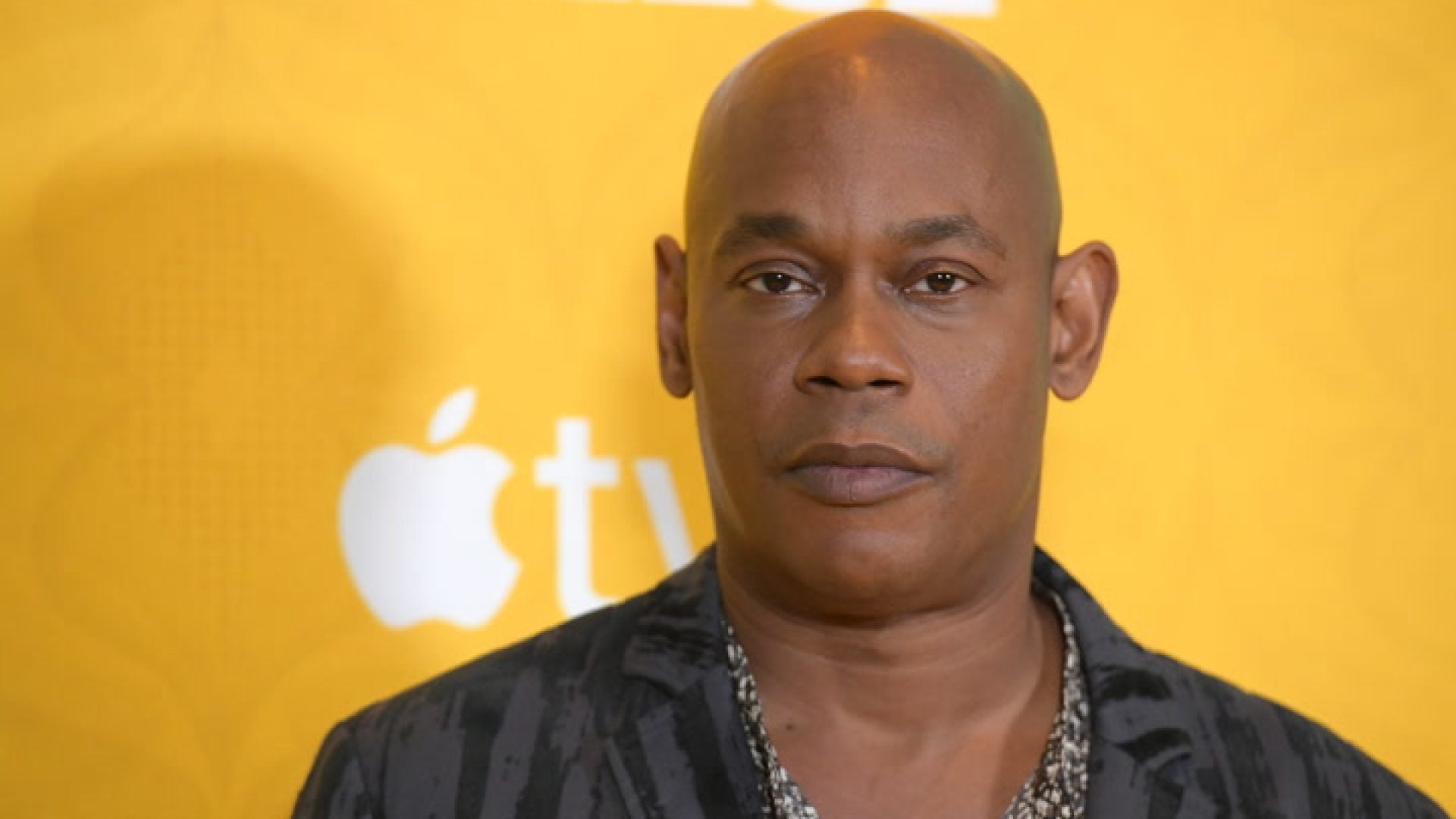

Several weeks before the much-awaited launch of Phoebe Philo’s eponymous label, a video of Iman accusing the English designer of racism resurfaced—reigniting calls for a boycott among Black consumers. In the video, the Somali-American model spoke out against Philo’s resistance to hiring Black models after being called out by the Diversity Coalition (an organization founded by Iman and Bethann Hardison to increase Black representation in fashion) for not including them in her shows. “Am I going to be forced to use Black models?” Iman recalled Philo asking. “No,” she replied. “There’s gotta be the right Black model for you. You know, there can’t be no Black model that’s not right for you.”

This incident occurred in 2013, five years after Philo took the helm of Celine and raised its profile to cult status. Season after season, the English designer put out a thrilling assortment of off-kilter pieces and highly coveted accessories that “every Black woman who has money bought,” Hardison told Evening Standard. Yet, Philo’s vision for the French luxury label did not include her Black Philophiles (as her fans are called) until 2015, when she hired the first Black model. More Black models would appear in subsequent Celine shows, suggesting that Philo had heeded Iman’s call.

When it comes to increasing Black representation, luxury brands continue to teeter between tokenizing and virtue signaling. Black shoppers accounted for 20 percent of luxury spending in the United States market in 2019, and the number is expected to increase by 25 to 30 percent, as ESSENCE reports. Although Black consumers drive the luxury economy and create trends that are constantly co-opted by the establishment, they too often have to contend with boardrooms, company cultures, magazine editorials, casting decisions, and campaign imagery that do not reflect them. As fashion editor Channing Hargrove wrote on Andscape, “The cost of luxury is higher for Black women. Not because the actual price goes up when a Black woman walks into a designer boutique, but because Black consumers also have to add in the cost of a brand’s anti-Black history.”

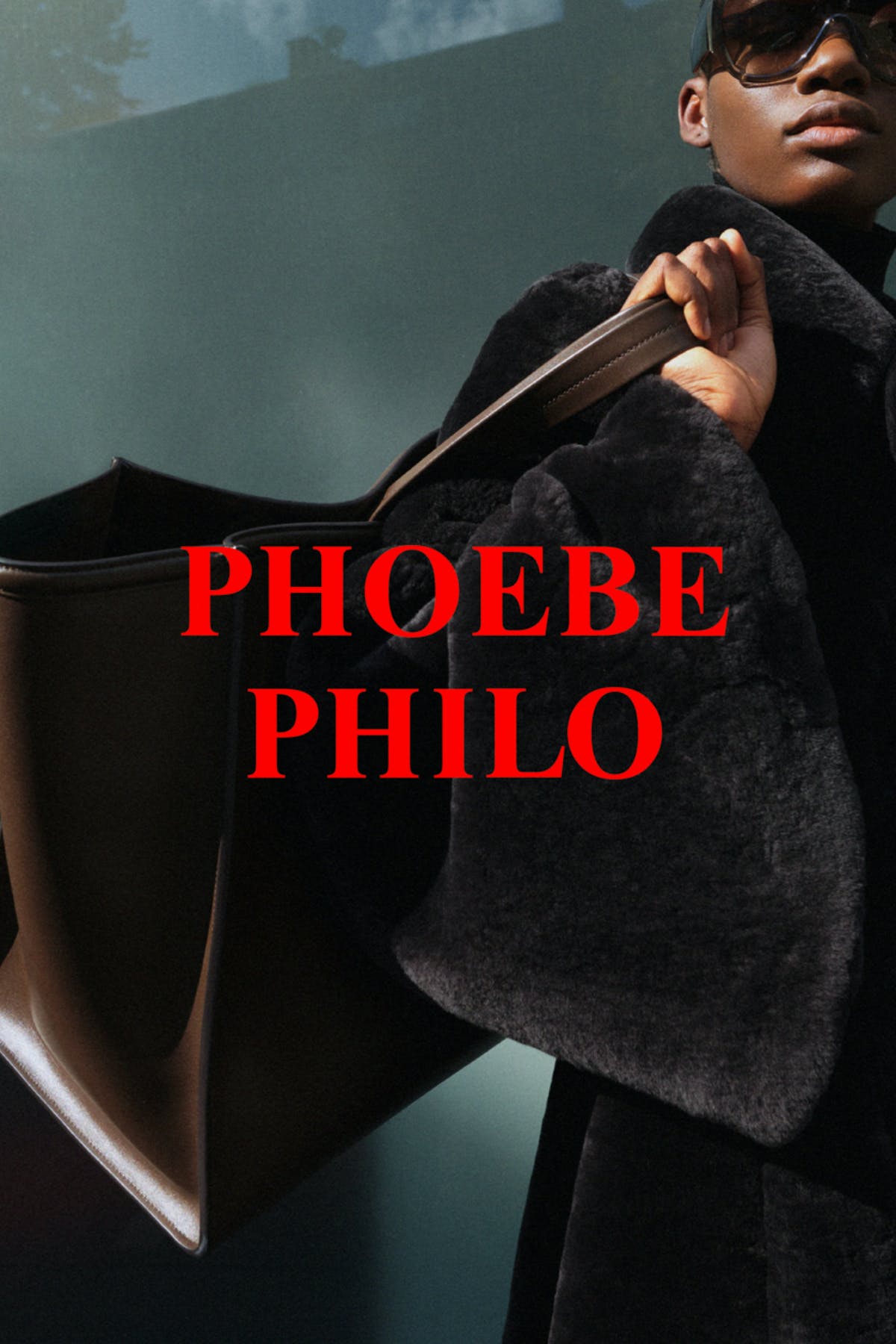

The year is 2023, and Philo seems to continue to take the Diversity Coalition’s petition into account. The first drop released on PhoebePhilo.com featured powerful imagery of models (several of them Black) clad in her new vision of what women want to wear. There were strong-shoulder blazers and coats; sharply tailored pants with intriguing details (one pair boasted erotic zips on each leg); high-neck tops and wool sweaters; fluid silk dresses falling into asymmetric hems; billowing embroidered trousers; edgy leather scarf-jackets; and of course, plenty of cool accessories. From square-toe pumps and boots to loafer-style shoes with intentionally crooked heels, the curation had all the hallmarks of memorable, practical, and self-assured footwear. The same goes for the handbags; a shoulder bag named “GIG” looked like a continuation of her hit Celine trio, while a series of ludicrously capacious bags showed that Philo is clearly in on current trends. Meanwhile, the oversized frame sunglasses and “MUM” necklaces will certainly be seen on everyone during Fashion Month.

With this launch, Philo reasserted her position as one of the most talented designers of our time. The clothes spoke of a woman who dresses for herself; her wardrobe isn’t trend-driven yet it always feels right for the moment. They are sexy but not in a stereotypical way, rejecting any notion of female objectification. The garments exemplified the concept of quiet luxury; blink and you might miss the nuances and out-of-the-box details that set them apart. Despite the steep prices (items ranged from $750 to $25,000), much of the edit sold out within the first two hours of release. Of course, this was to be expected considering the devotion of her fan base, but the fact that people spent thousands of dollars on clothes and accessories they didn’t get a chance to see beforehand is a testament to Philo’s genius.

Yet, for all its success, Philo’s first drop fell short of catering to plus-size bodies. The clothes were only offered up to a size 14, while studies show that the average American woman wears sizes 16 to 18. “Imagine starting a fashion brand in the year of our lord 2023 and NOT considering size inclusion to any degree,” wrote fashion editor Gabriella Karefa-Johnson on Threads. Indeed, considering all the resources the Central Saint Martins alumni has access to (her venture is backed by LVMH) and following a particularly bad season for plus-size representation at Fashion Week, this—we’ll call it—oversight feels egregious and inexcusable. Philo’s Celine wasn’t size-inclusive; her eponymous label isn’t either. “It’s particularly sad when the designer has had years to reflect on the ways in which the industry developed (minimally) in the time they’ve been away and choose to reject the progress in favor of exclusion,” Johnson added.

While Phoebe Philo’s latest venture has been embraced by fashion critics and her legion of fans, underneath it all lurks a sense of soullessness. The clothes, although well-constructed and fashion-forward, come with a price tag that is out of touch with the economy as well as the growing accessible luxury movement. And yet, the high price point has always been part of Philo’s modus operandi. Her time at Celine was also marked by high-end goods (though more attainable than those in her eponymous label), which sent aspiring consumers and members of the fashion elite into a frenzy, trying to be the first to acquire them or actively sourcing them on resale platforms. In the six years since Philo stopped designing, the U.S. fashion luxury market has evolved to welcome brands like Christopher John Rogers, Sergio Hudson, LaQuan Smith, and Theophilio. These labels may have similarly high price points, but their fashion philosophy is above all, inclusive and full of life. Philo would benefit from taking notes from these creatives on how to make a lasting impact, which might push her into a more culturally relevant conversation rather than the one she’s always led: catering to the moneyed elite.