The most important fashion cities are considered to be New York, London, Milan, and Paris. These capitals, however, are not the only cities where fashion matters. And in a country like America, unique configurations of clothes are just about everywhere, even in places where one would least expect it, or that tend to be disregarded, like the South. But as W.E.B. DuBois once perceptively proclaimed, “As the South goes, so goes the nation.” The Southern makers, retailers, record-keepers, and consumers that have enabled fashion to go on have shaped the region as an arbiter steeped in history. In the South, fashion has always had something to say.

The Wall Street Journal reported in July that HBC, the parent company of Saks Fifth Avenue, had acquired Neiman Marcus Group in a $2.65 billion deal. The original Neiman Marcus store, established in 1907, sits on Main Street in Downtown Dallas with some corporate offices just levels above its sales floors. Not long after the acquisition was announced, Sarah Hepola wrote in The Dallas Morning News that the storied retailer “defined life in Dallas.” Neiman’s, she said, “is about the promise of transformation,” “a commerce story and a Dallas story,” but “also an American story” emblematic of a country known for reinvention. The upscale department store appealed to the taste of its local clientele and well beyond it.

Annette Becker, historian and director of the Texas Fashion Collection, points out that as ready-to-wear garments for women were produced at a scale that could be spread across the entire country postwar, “an American fashion identity developed, and regional fashion identities certainly developed.” She notes how Stanley Marcus, who once ran his family’s business, Neiman Marcus, would travel to London, Paris, and Italy to work with designers on “how to scale up following the war to feed the voracious appetites of American commerce.” When he schooled them on the particularities of America’s fashion system—its rapid manufacturing needs, for example—he also caught them up to speed on the varied tastes and climates that shaped peoples’ wardrobes across the nation. The merchant would have the ear of Emilio Pucci, whom he “educated on how to translate the Italian way of dressing for folks shopping at Neiman Marcus because the climate in Italy is not terribly different from the climate in Texas,” Becker explains.

Perhaps this is what gets lost in conversations about culture and influence in fashion: that consumers, like designers, whose contributions cannot be confined to a city or two in a country as big as the United States, also determine its significance. Hence why a recent tweet claiming that New Yorkers laid the groundwork for Southern styles of dress struck me and a slew of other X users as odd, and wrong. To think, nonetheless purport this is ahistorical, egregiously shortsighted, and, inevitably, anti-Black. But it isn’t surprising. Many Americans still see the South as a backward place devoid of contemporary relevance. Meek. And marginal.

As the country’s largest, most populous region, this couldn’t be further from the truth. And, what’s more, it is Southern soil that many Black Americans call home and that our most celebrated Black fashion titans have hailed from.

I’d just finished giving a lecture at the University of North Texas, which hosts the Texas Fashion Collection when I turned up at Becker’s office eager to pore over the accessions. Like a kid in a candy store that just so happens to be her job, she slipped on a pair of white gloves and asked which designer’s work I wanted to see first. Without hesitation, I said “Patrick Kelly!” The trailblazing designer, a Mississippian was the first Black and American member of the Chambre Syndicale’s ready-to-wear division, boasting a couture clientele such as Madonna, Cicely Tyson, and Gloria Steinem, to name a few. Becker pulled two of his designs: first, a tan, one-shouldered mini dress trimmed with wooden buttons that form a heart at the center; followed by a Spring 1989 pinstriped Black denim skirt suit with white, yellow, and red dice buttons.

“The buttons that become really prominent in [Kelly’s] practice are because of a matriarchal figure in his life bringing home buttons in this kind of home-making way to patch up things, to renew things,” said Rikki Byrd, a curator and assistant professor of visual culture at The University of Texas at Austin. “They shaped what became this Parisian brand started by a Black Southern man. We can marry these elements and moments in which items that are not seen as luxurious or fashionable have a particular preciousness for Black folks that influence how we dress and how we design,” Byrd added.

Take “Sunday Best” dressing, a tradition that began in the Black Southern Baptist church, now observed across geographies, denominations, and even social settings, exemplifying a most dignified form of self-presentation, a bootcamp in impression-making. I would be remiss not to acknowledge Ridgeway, South Carolina native Sergio Hudson, a sartorial trustee for the women on 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue and Number One Observatory Circle. Or our beloved Andres–Leon Talley and 3000–men with style so painstakingly attended to and elaborately shown so as to remind us that dandyism ultimately lies in the hands of the man.

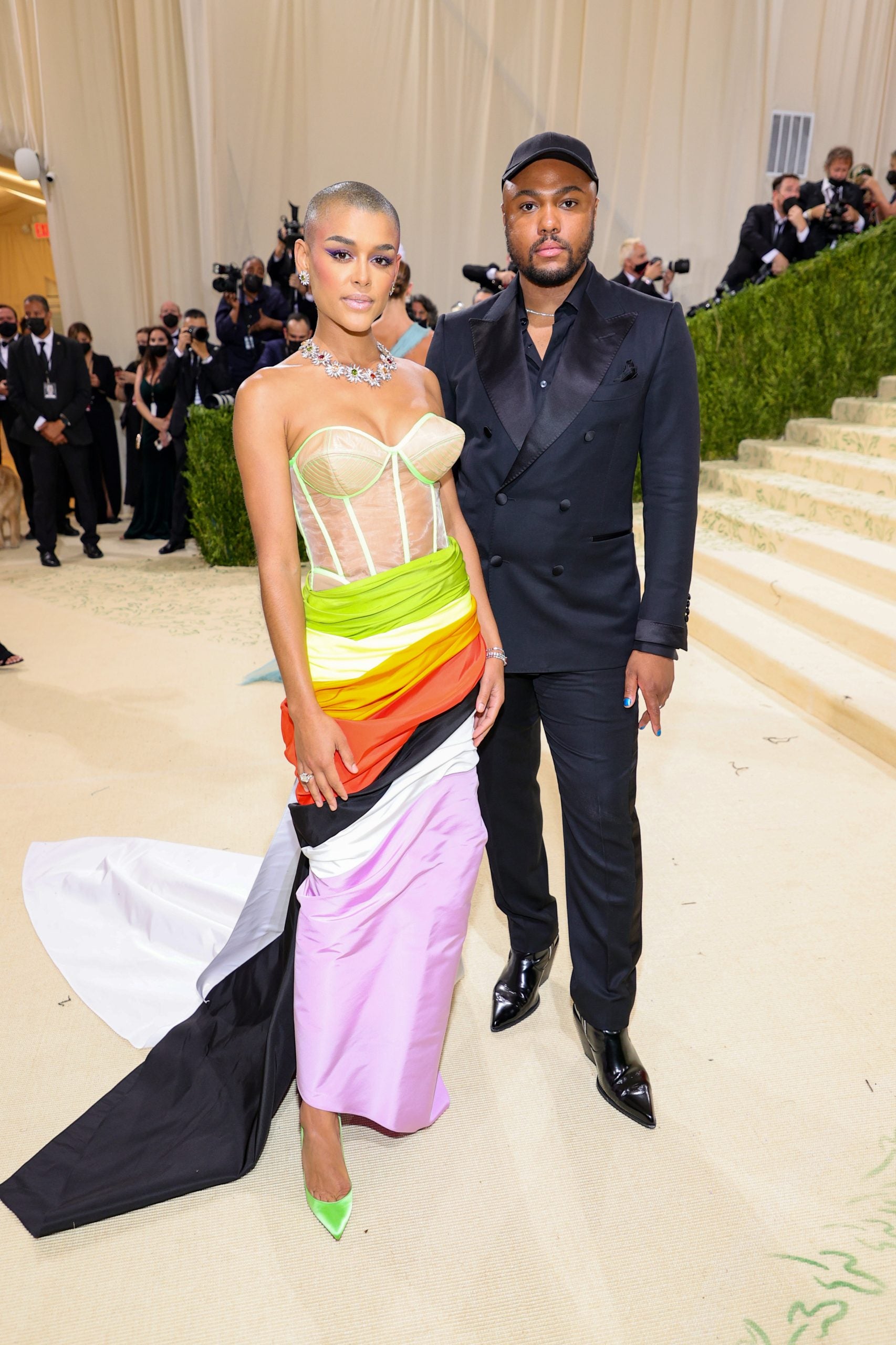

An avowedly Southern-Francophilian Talley donated much of his work to the “ALT Collection” at Savannah College of Art & Design, where Christopher John Rogers who is originally from Louisiana trained. For the 2022 Met Gala, “In America: An Anthology of Fashion,” Rogers paid homage to Elizabeth Keckley in a dress he made for actress Sarah Jessica Parker. Keckley, born into slavery in Dinwiddie County, Virginia, purchased her freedom in 1855 and went on to make her name as a dressmaker, spending time in Washington, D.C. dressing First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln and the wives of Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

It is assumed that her silk quilt, made between 1850 and 1875 with floral motifs and raised embroidered eagles, contains scraps of fabric from dresses she sewed for her clients, including Mrs. Lincoln, according to the Kent State University Museum. The Black quiltmaking tradition in America is originally Southern. Many of us are familiar with the patchwork blankets that have found themselves tucked tightly in our grandmother’s closets, extra covers for family sleeping over. However, their qualities have more to do with Black Americans’ clothes than we may think of everything to do with them.

In a 1998 study, the late professor and dress theorist Gwendolyn O’Neal applied the African American quiltmaking model, to get to the nuts and bolts of how we dress. “The visual balance created between precision” and random combinations, “loud colors, large scale designs and multiple rhythms” still exists. They explain the aesthetic variance, eccentricity, and cultural pride with which we dress, once and maybe still offensive to the White Western eye.

This is also a reminder of where we come from, an embrace of our differences in a world that incentivizes conformity. Southerners put forth a kind of dressing that possesses that spirit and articulates most assuredly. That’s as needed in our clothes as ever, and it isn’t going to change – below and above the Mason-Dixon.