It’s the afternoon of a slowly foreshadowing spring, and figurative artist Tschabalala Self is glowing on the heels of a myriad of exhibitions. A darling in the art world, the Harlem native has shown at Art Basel Grand Palais, the New York High Line, Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design in NYC, and a host of esteemed galleries. Within two weeks she’s preparing to present at the opening reception for The Illusion of The Self at Longlati Foundation in Shanghai, and the day after, her work will be showcased at the Perrotin in Paris in place of an exhibit on Black femininity by Pharrell Williams. Concurrently, her exhibit Dream Girl is on display at Jeffrey Deitch in Los Angeles.

As one of the most identifiable contemporary figurative artists, the value of Self’s work has increased by nearly thirty times its value over the past decade, with some pieces valued at well over $300,000 at Christie’s auction house. Her work has decorated the homes of Alicia Keys and Swizz Beats, Aurora James, and Pusha-T, who name-dropped the artist in “Paranoia,” a Drake diss that was set to release on Pop Smoke’s album. (“I might even buy a home out in Mississauga, On my walls, have scrawls of Tschabalala’s”.) Inspired by the likes of Faith Ringgold, Mickalene Thomas, Jacob Lawrence, Romaire Bearden, and Wangechi Mutu, Self illustrates the modernity of Black life and, more specifically, the iconographic significance of the Black female body in contemporary culture.

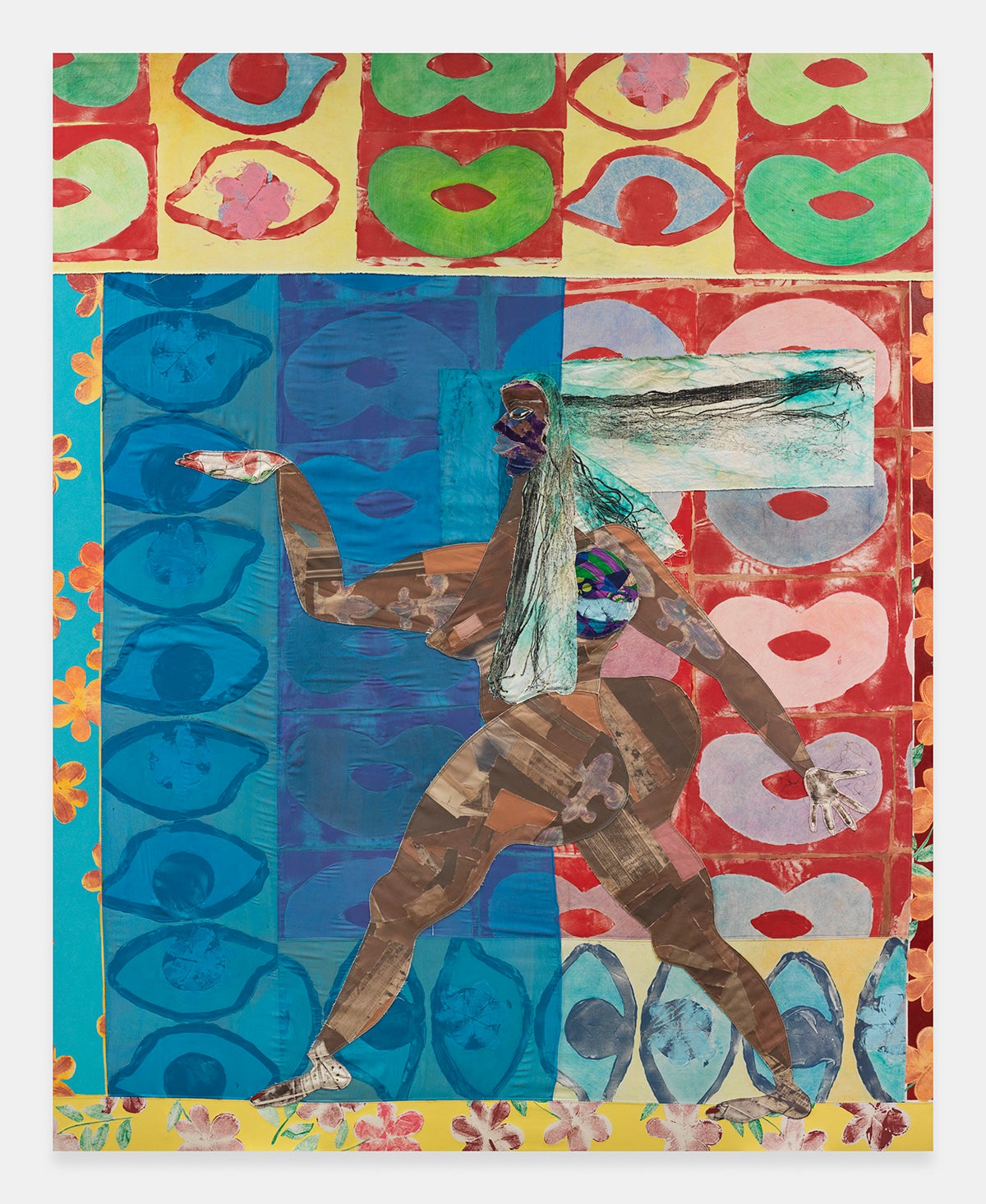

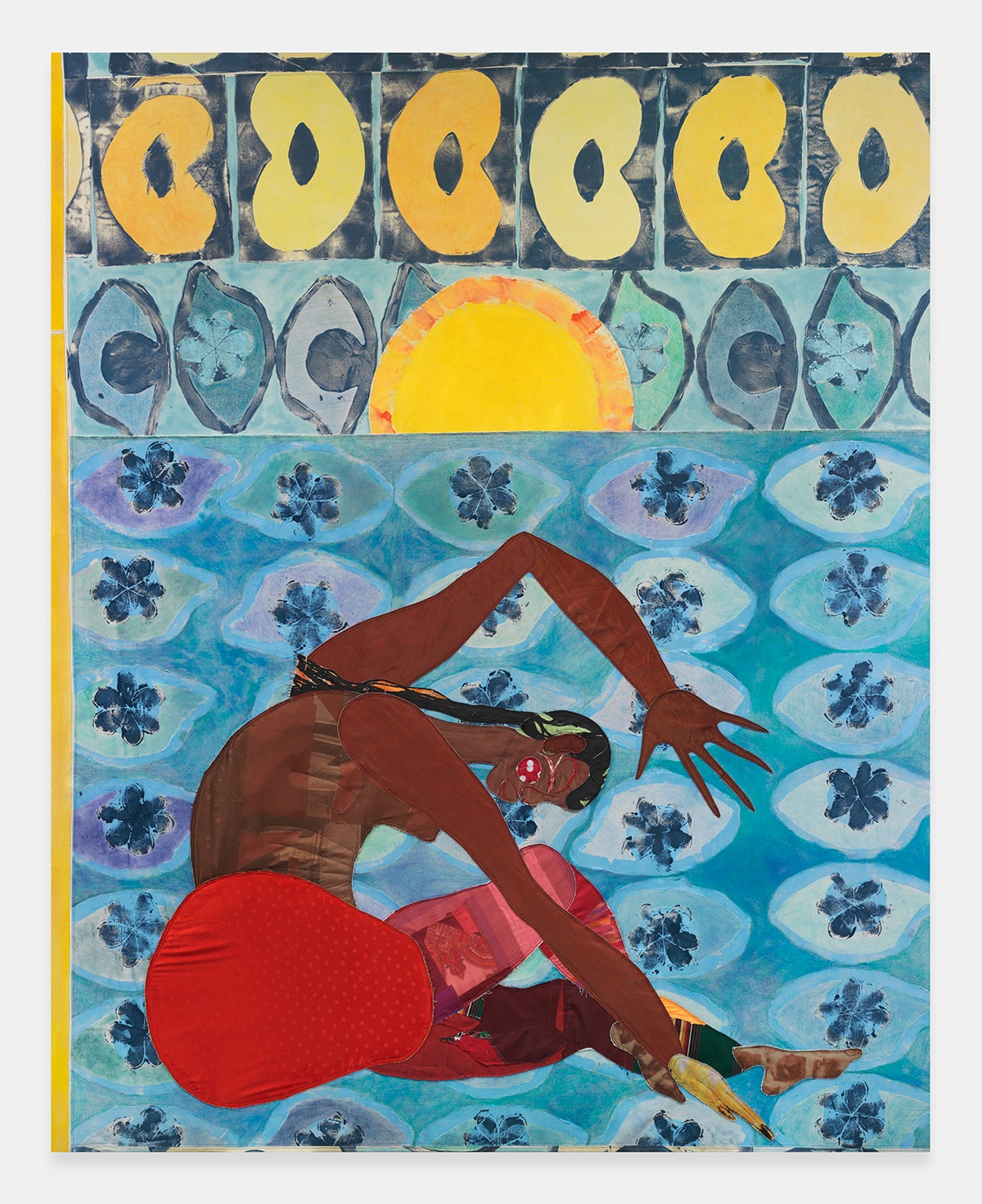

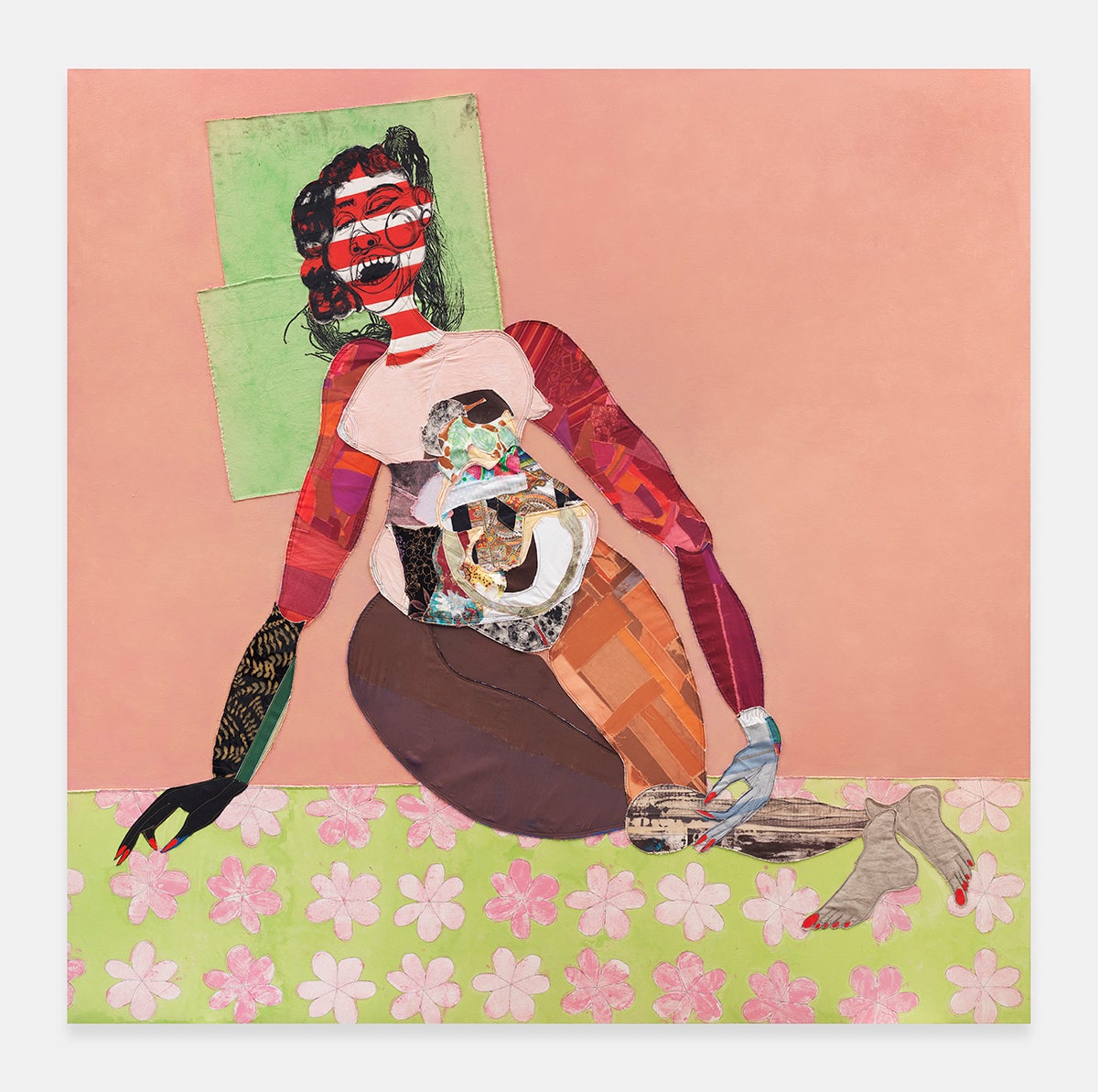

The artistic universe Tschabalala has created through her work feels glamorous, as she often fashions full figured characters in lipstick, with painted and elongated finger nails, and freshly painted toenails if they aren’t wearing heels. Colors are vivid, and her alluring images evoke bemusement and wonder as each character she illustrates appears to have a life of their own. In gazing at her collections, one could be curious as to whether the women portrayed are rich and carefree, or rather that the process of beatification and how they present themselves makes them appear that way. Perhaps, art imitates life as a model for how Black women tend to show up in the world.

Nonetheless, Self’s portraits feature a gamut of audacious protagonists illustrated by synthesized materials that range from oil and acrylic paint to gouache, coloured pencils, flashe, canvas, and discarded fabric. Each material contributes to an image’s symbolism at large, from its color, texture, or where it was acquired. In tandem, Self’s pieces encapsulate syncretic use as she employs methods such as printmaking, sewing, drawing, and painting. These articles and practices align with Self’s idea of collage as representative of selfhood and that humans exist in multiple dimensions.

Perhaps one of the mystiques in Self’s work is that she has managed to fashion humanity in her exhibits with each character critically developed and their personality and desires accounted for. Protagonists within Self’s artistic world are often displayed in liminal places to infer a particular emotional or mental state. As a result, viewers focus on the thoughts and feelings of characters as opposed to their physical location. “[The liminal space] is a metaphor just for this humanistic experience of being in between places,” says Self. “Even if you look at it from a purely secular perspective, time is always moving forward. So you are always in between places.”

Self fashions characters from a moral neutrality, intent on depicting reality. This approach to her characters is what makes them aspirational. “I think that sometimes, especially with Black figures, the idea of being magical or exceptional is a bit oppressive,” Self says pragmatically. “Not all situations call for being respectable, especially a lot of the situations [Black] people are put in,” she continues. “For me it’s really important that my figures feel like real people and because they’re real I find them personally aspirational. I feel like because they’re real, they’re free and not beholden to anyone’s expectations.” This motif of autonomy, freedom, and agency appears in several of her iterative works.

“People who are made in their daily life to feel marginalized, it’s important that they understand that they are, regardless of what is said and what kind of circumstances people try to shove onto them—that they are indeed free,” the artist explained.

For Art Basel in Paris, she presented a solo exhibit, My House at the Galerie Eva Presenhuber. The aforementioned consisted of two sculptures, functional art objects as furniture, and paintings. Within this particular project, Self reimagines Sarah Baartman, one of the first accounts of Black women being sex trafficked, as a free woman in Paris. Baartman, was trafficked from South Africa by a British doctor to be paraded around Europe’s freak shows during the late 1700s.

Attendees of these circuses would often touch Baartman without her consent, and while many details surrounding her life and death differ by 1815, she’d passed away at twenty-six years old. According to the artist, Baartman had no autonomy even in death. Her brain, skeleton, and genitalia were on display at a museum in Paris until the 1970s, and in 2002, the French government finally agreed to return her remains to her hometown in South Africa.

Nonetheless, indicative of the exploitation of Black women’s bodies, Sarah Baartman’s story is also relevant to the 2024 discovery of 12-year-old Dalisha Africa’s remains at Penn Museum. This contributes to the idea of Black people as a spectacle and moreover, a commodified product to be consumed even in death, destruction and exploitation. This particular thought process, constituted the existence of the Transatlantic slave trade which enslaved nearly 12.5 million Africans and ultimately substantiated the United State’s as one of the richest countries in the world. Self believes that Baartman’s story is one that Black artists in particular must be aware of citing an urgency for understanding the need for Black people fashioning Black images.

Her latest exhibit, Dream Girl, incorporates fantasy as a means of challenging the construction of self and femininity. Inspired by Hollywood as an incubator for reinvention and transformation, Self’s protagonists are full-bodied and autonomous, each embodying her view of an aspirational woman: “There’s a conjure woman, a woman connected to the supernatural and who has this ability and power,” she said.

“Dream Girl is the namesake of the show, and she’s super carefree and beautiful and one that you want to be around,” the artist continues. “There’s Timeless, who I think of as a performer. Timeless has this beauty that was captivating throughout her time.” These characters exist as fantasies of people and Self utilizes silhouettes, expressions, hair and nails as signifiers of femininity throughout the exhibit. Moreover, Self believes that femininity is more of a construction and malleable.

In the exhibit, a poem outlines a wall written in black charcoal as Dreams both scary and bright are rarely right, but often true. To the figurative artist it means nothing and many things simultaneously. “I think a lot of times, Black people, especially Black women, are told a lot of things about ourselves, and I don’t think that they are right or relate to the ultimate truth,” she said.

“They are true in a sense in that these are the limitations within this construct that we have to intellectually understand to navigate. But I disagree with internalizing those beliefs because I think those beliefs are ultimately not right,” she adds.