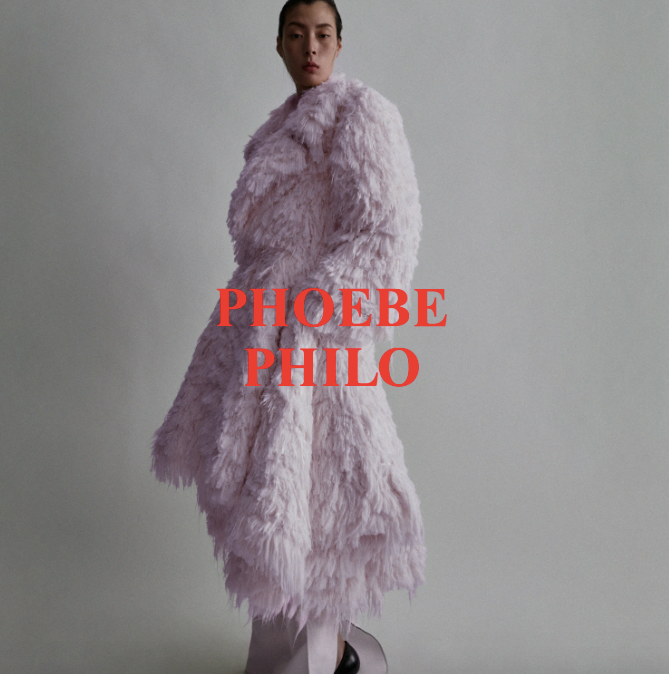

Last week, the fashion world welcomed two major designer drops with great fanfare. First, Phoebe Philo—the minimalist designer who revived Celine in the 2010s—launched her eponymous label two years after announcing the venture. The first edit, A1 as she called it, featured a range of pieces that felt both new and familiar to longtime fans—from sharply tailored coats and asymmetrical dresses to understated tops replete with unexpected details and deliciously executed pants, plus a contemporary assortment of square-toe pumps, loafers, and functional bags. The items ranged from $750 for fashionable ski goggles to a reported $25,000 for an oversized shaggy coat, and the entire line sold out in a matter of days. Despite the blatant lack of size diversity and prohibitive price points, the fashion industry deemed the first release successful.

Then there was Kylie Jenner, who needs no introduction. The youngest of the Kardashian-Jenner clan launched the new label she had teased on Instagram a week prior, KHY. It consisted of 12 pieces, with the majority leaning towards an oversized aesthetic and crafted predominately from leather. The exception was a few tees and a pair of leggings. The drop, created in collaboration with Berlin-based designer Namilia, featured two standout Balenciaga-esque jackets–a trench coat and a cropped hooded style. However, these pieces were visibly less meticulously crafted, constructed from cost-cutting materials such as polyurethane leather. There were faux-leather crop tops, pants, and fitted strapless dresses, all serving as sartorial armor and conveying a tough-girl attitude. With this launch, Jenner aimed to make great fashion pieces accessible for everybody, as she told Elle magazine. “How do we make the best stuff that feels so luxurious and looks amazing that everyone can experience?” she said.

In reality, the luxuriousness of the drop doesn’t seem to translate effectively. Doubts regarding quality surfaced primarily due to concerns about the material composition, and initial try-on experiences provided little reassurance. “I will say these are faux leather, and you can really smell it,” TikTok star Charles Gross, who was among the first creators to receive KHY pieces, said in a video. As a concept, KHY has potential (the label is also intended to highlight design talent who may not otherwise become widely known); Emma and Jens Grede, the married couple behind several Kardashian-owned ventures—namely Skims, Good American and Safely, also have a hand in Jenner’s new line. But contrary to Skims, which filled a white space with flattering and incredibly effective shapewear, KHY doesn’t seem to have found its point of differentiation. The first iteration fell short in terms of establishing credibility, as the featured pieces struggled to embody a genuinely wearable aesthetic or authentically reflect Jenner’s distinctive style (although she models them well). While items did sell out within hours, Gross’s review suggests a significant probability of consumers opting for returns after a hands-on assessment.

The timing of these drops is interesting as it seems to epitomize the ever-widening gap between good and wasteful fashion. The cost of apparel has never been higher, yet the quality of clothes has been on a steady decline since the 1980s, thanks to the rise of fast fashion and a series of free-trade agreements that have enabled brands to outsource the cheapest materials and labor from developing countries. Polyester has thus become the de-facto fiber used by the majority of brands, making their products less durable and non-biodegradable. And despite the synthetic fabric costing a lot less than natural fibers, a range of companies (from luxury houses to trendy labels and prestige brands) are still overcharging for their poly-incorporating designs.

Consequently, shoppers are paying premium prices for garments crafted to wear out prematurely or swiftly fall out of fashion–an approach known as planned obsolence. This practice perpetuates an endless cycle of consumption, ultimately harming the environment. On one hand, the clothes that are good, as in considered, practical, made from premium sustainable materials, and timeless—as seen in Philo’s eponymous label—command price points that are completely out of reach, and this has more to do with branding and marketing than actual production costs. In fact, inflation (coupled with the quiet luxury trend) has seen brands dramatically increase their pricing, the better for people to perceive their offerings as valuable investments despite their subpar quality. On the other hand, fast fashion giants like Shein, Zara, and H&M replicate runway trends at a seemingly affordable cost—though this affordability comes with the caveat of overlooking their track record of labor violations and human exploitation. In the process, these corporations are eclipsing everyone in the middle—from conscious or more sustainably-minded labels to emerging designers, forcing them to also compromise or lose market share. While KHY doesn’t exactly fall in the fast-fashion category, it follows in the footsteps of brands that tell a good story yet still offer products of questionable quality.

Access to quality fashion has always been about economics and a brand like Phoebe Philo was never designed to be in everyone’s hands. While this is widely accepted, it still sends the damaging message that only the elite (that one percent of the population who can easily swing $1,600 for a sheer scarf top or $4,200 for a tailored blazer) are worthy of quality goods. When it comes to retail, it feels like consumers who aspire for better wardrobes on a budget often feel compelled to compromise. However, the reality is they need not settle, as there exists a middle ground––it’s just increasingly challenging to discern and access. Brands like Patagonia, For Days, Knickey, and fashion designers—big and small—like Stella McCartney, Mara Hoffman, and Nia Thomas are actively challenging the system. Although they are also plagued by issues of accessibility, desirability, or visibility, they represent a positive way forward. Then there is the vintage market that offers the chance to collect quality goods from past decades as well as resale, which allows another opportunity to own once-coveted items. These initiatives may still require development, but they are shifting the paradigm and promoting a new world: one where fashion is equitable, sustainably minded and community-oriented.