Just by glimpsing through Elle Brasil’s September Issue, where Viola Davis graces the cover, it’s evident that no one forgets a MAR+VIN shoot. Davis, an EGOT winner, transforms into a statuesque figure behind the lens of Marcos Florentino and Kelvin Yule, adorned with a black ostrich feather headpiece in one frame, an eccentric leather hat by Cecilio designs in the next, and in a full-body shot, she exudes elegance in a Loewe printed dress, gloves diagonally accentuating her curves, and Schiaparelli heels. Throughout the magazine, Florentino and Yule capture Davis with a finesse akin to sculpture at the Venice Biennale, where she becomes not just notable for her prolific body of work but the “magnum opus” herself. Such is the magic of MAR+VIN, where every subject under their gaze is transformed into a moment.

The duo and couple create moments that make magazine spreads into coffee table art, immortalizing their subjects with each click of the camera. Last year, Suyane Ynaya (Elle Brazil’s Fashion Editor), commissioned Florentino and Yule to shoot with neo-soul singer Erykah Badu during her performance in Brazil. Badu, intrigued by Afro-Brazilian culture and ancestral knowledge, collaborated with the duo to create a shoot deeply rooted in worldbuilding. The images featured Badulla Oblongata sporting her signature oversized top hats, one of which strikingly doubled as a dove’s cushion, and the other matching a monochromatic green suit. In one of the most beloved shots, Badu stands in a red Von Trapp dress amongst Mestre Didi’s wooden artwork. “We created the story based on Afro-Brazilian roots and culture and we wanted her to represent the spiritualized mother who mediates contact between the divine and the earthly, the messenger, the doula.” writes MAR+VIN in an email. The glossy spread enraptured social media annals and Badu crowned it, the best shoot of her life.

Afro and Indigenous culture is standard in MAR+VIN’s visual storytelling.The image makers are devoted to democratizing fashion and illustrating the vastness of Brazil’s rich culture. Unbeknownst to many, the country is home to the largest African Diaspora outside of the continent itself, and in 2020, TIME magazine published an article stating that 56% of Brazilians identified as Black while Afro-Brazilians comprised: 4.7% of the country’s top 500 companies, 18% of congress, 75% of the country’s murder victims, and 75% of police fatality victims. In a story for The Washington Post the artists likened Brazil’s policies as genocidal and irresponsible. Yet, through photography, the duo work to course correct by accurately portraying the country’s majority Afro-Brazilian and mixed-race population. Neither Florentino nor Yule shies away from the label of political art.

“The truth is that our work reflects who we are, and who we are is a reflection of all the factors that make up our human identity,” MAR+VIN tells ESSENCE.com. “Fashion is a reflection of societies, of the desires, dreams, and imaginations of those who build it. If I am a political body working in this industry, my art will consequently reflect who I am. Otherwise, it wouldn’t make much sense to me.”

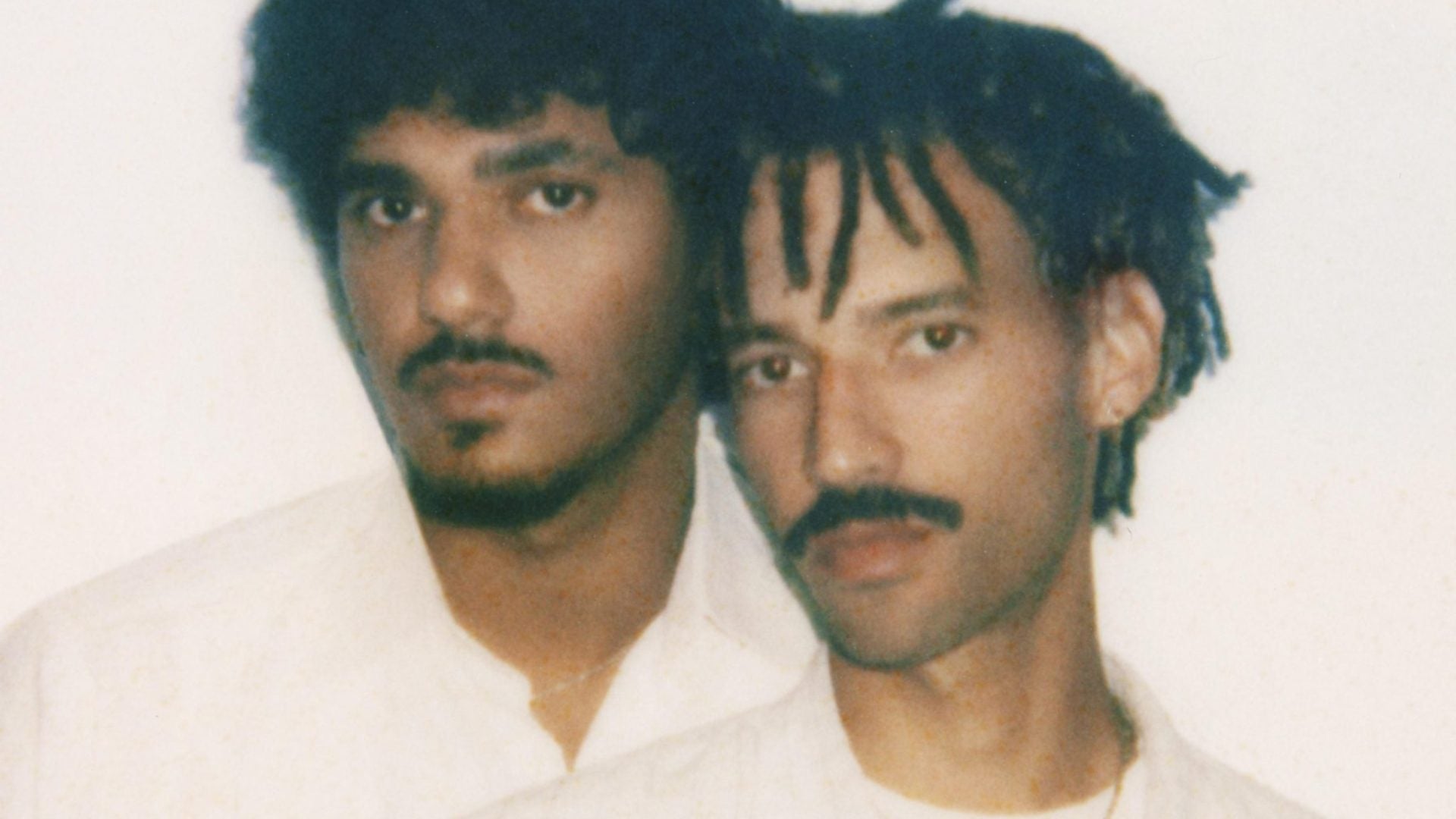

The vibrancy of Yule and Florentino’s identity and consciousness are inextricably present in the soul of their visual narratives, leaving an indelible mark on their artistic portfolio. Marcos, hailing from a small village in Piaui and working as a graphic designer before venturing into photography, and Kelvin, influenced by his childhood memories on Bahia’s coast, bring unique perspectives shaped by their culture and career backgrounds. ESSENCE.com had the pleasure of speaking with the two photographers to discuss their creative process, collaboration and personal journeys in Brazil.

ESSENCE: How did you both get your start?

Marcos: Fashion has always been a place of fascination and a realm of expansion. Dolls fascinated me with their clothes and the possibility of creating additional garments for them. I grew up watching my mother and grandmother sew, so textiles were always there. I would draw croquis, and at some point, I thought I would become a fashion designer or something similar. Despite having little contact with photography as a child, the concept of capturing something and immortalizing it in physical form has always fascinated me. When I turned 18, I moved to São Paulo. My first years there were hell, but I applied for a scholarship to study graphic design, and in college, I deepened my understanding of analog photography processes. After a frustrating job experience, I used the money from my termination to buy a camera and began publishing my work online. I was doing self-portraits, using paints on my body like I painted canvases, and my photographic process became a great mix of all my little obsessions.

Kelvin: I never thought I’d work in fashion or be a photographer. Astronaut, biologist, and even preacher crossed my mind as a child, and as soon as I mentioned the last one, I was scolded by my mother, who said: “My son, preacher doesn’t earn well”. In Brazil, [we]take a general knowledge test to place at any university, preferably state or federal, which are the most renowned and free. I ended up choosing to study journalism, and it was during this period that I began to get closer to photography and audiovisuals, first as escapism, and then as a form of self-expression before moving on to photojournalism and portraits.

ESSENCE: Can you tell us about the conceptual process of your artistry?

M+K: It all starts with a spark, a feeling, a will, a wish, an obsession, or anything that we can identify clearly and transform into an idea. Being two individuals with strong ideas and opinions it’s not always an easy task, we can sometimes disagree on a lot of things. When the creative direction comes from us, before presenting it to other creatives we have to have an aligned concept and idea, which usually ends up being a bargain of both of our visions. As a duo, it all has the premise of a collective and collaborative practice. Each person we work with has a history and a background that can add to the story we’re trying to tell. The magic happens on the set because even when we have everything in place sketched, we have to be open to the casualties and interpret them in the best way possible.

ESSENCE: Marcos, you mentioned gaining access to the internet at 18. What was the first thing you looked up when you gained access, and how do you think your exposure to the internet has impacted your life?

M: I was an imaginative child, and my older sister, who is a public school teacher, encouraged me a lot, so I spent much of my time immersed in books and often fantasizing about mythical entities, particularly those from Brazil’s rich folklore, like the saci or the Curupira. I had a space between the juremas trees where my girlfriends and I would gather to share stories. When I acquired my first computer at 17, and my school had computers with internet access, I would save pages and take them home to read offline. At that time I was curious to learn how to manipulate images, and much of my skills and theoretical knowledge about image processing were acquired that way, free from the distractions of instant messaging. I searched for information in other forms and used my time to refine what caught my interest. I’ve always been interested in creating, so I experimented with everything I could lay my hands on, from painting to sculptures with wild clay. My mother was always an inspiration to me and a great artist. Her hands were magical and could create anything she set her mind to, so I think I inherited a bit of that from her.

Kelvin, you studied journalism in college, what topic specifically sparked the curiosity that you bring to your practice?

K: I believe that journalism has made me more observant, seeing and trying to understand the things around me from different points of view has certainly helped me improve what I do today. Understanding that there is no absolute truth, understanding how to write better, having studied semiotics… The human side of it, the ethics, the balance between the emotional and the rational. I remember the afternoons when I would go to the TV labs to satisfy my curiosity and see how the editors worked, and what programs they used. having directed a short film, having covered concerts, protests and accidents. Having talked to people on the street and listened to their outbursts, having done projects about the invisibility of people in situations of social vulnerability, having protested for causes I believe in… Everything has made me who I am.

ESSENCE: How have you navigated the development of your identity in Brazil?

M: I always knew I wasn’t white, but I didn’t know exactly what I was. Coming from a family of Black and Indigenous people, the lack of reference on television, one of my main sources of information at that time, confused me with my identity issues. Growing up in a really small village, with people who were interconnected by family ties and had similar features, gave me a sense of belonging and distanced me from the idea that I was different. In a country where more than half of the population considers themselves as Black, racial topics aren’t addressed in schools, so I had access specifically when I found myself in a big city and realized that I was visually different from the majority. I also had access to the city’s racist and xenophobic patterns, which made me want to delve deeper into the roots of these problems and try to find myself in this complex racial entanglement that is Brazil.

K: During my childhood, I didn’t have many references where I could be inspired and feel represented, but I always knew I was “different” because people always made a point of seeing things in me at a time when I didn’t even see it about myself yet. For many people, saying that someone was Black was almost offensive, leading to the use of euphemisms and diminutive terms to sidestep the issue. I was always “forced” to cut my hair, firstly because of the imposition of a standard of beauty that said it was “ugly”, and this was ingrained in me until a few years ago when I freed myself from these bonds and experimented with all the possibilities (of which there are many) that my hair could offer me. When a movement of Black youth began to emerge throughout Brazil combating racism and valuing Black ancestry it influenced much of what was produced in fashion, music and the visual arts. A new aesthetic emerged that mixed Afrofuturism and Afropunk references with our own reality, aesthetically similar to the Fashion Rebels of South Africa. The movement helped me process building my own identity and understanding myself as a Black person, as well as starting a process of building my photographic work.

ESSENCE: Brasil like the U.S. has a brutal history regarding race specifically, at what point did you realize you wanted to create images that reflected the diverse Afro-Brazilian population?

M: It was an urgent need. When we arrived on the scene, we were still raw, trying to understand how everything worked. The ground was really white and hostile. Black and brown models were often confined to specific and stereotypical scenarios. It was almost common sense that if there was one model to be featured in an editorial, it would be a white one. For us, it was never a trend; it was a need. We wanted those people to be seen because we also wanted to be seen. To be in places that they were not usually inserted, with respect, care, and lighting that accurately depicted the beauty of Black and brown skin.

ESSENCE: Can you talk about the process behind your Elle Brasil covers of Viola Davis?

M: When Luciano Schmitz (Elle’s Brasil Creative director) invited us, Viola was working on the promotion of her forthcoming film “The Woman King” and it was reverberating in our heads. We were invited by Sony Pictures to a private screening of the movie before its official release and wanted to relate that idea of representing the strength, courage and bravery of a warrior woman to the history of Viola itself, one of the most emblematic and important figures in our history. We studied many ways of how to materialize all these feelings and eternalize them in images.

K: Unfortunately, I couldn’t be physically present on the set because the American embassy in Brazil refused my visa four times. It was the first set we hadn’t been on together since the day we met and because of it, we set up an iPad on a tripod where I was connected to a video call and had a view of what was happening on set while receiving the images in real-time and doing the tech from São Paulo. I think we had about three hours with her on set.