Dreams, as we know, are difficult to define. How often have you found yourself on the border of a new world, slipping into the threshold of something uncharted, only to have yourself snatched from the promise of sleep? Before a scene can crystallize, before any wisdom can be extracted, you’ve been blunted by a neighbor’s pounding feet or blasting music, distressed by the pings of an irritating iPhone. Disturbed and disrupted, you know as I know, that once the senses are startled, the peace required for dreams evades.

In our waking world, a world polluted by the monistic psychologies of an invading culture, dreaming is often considered frivolous. We are expected and encouraged to focus on reality, by which reality is defined by external, social, material, and political conventions. Beshat brains remain enthralled by images of the day world only, remaining ignorant of intra-psychic possibilities and the disciplines required to create them. But every dreamer knows ancient secrets: that (a) dreams are never any greater than the dreamer and (b) dreaming is serious business.

“True luxury,” Olivier Rousteing tells me, “is when you have access to your dream.” Curled against a cushioned leather chair, smoking a thin cigarette with utmost grace, Rousteing is a portrait of Moorish elegance. Potted plants surround him and a wall of gold-plated mirrors enhances the Parisian sunlight which streams from every angle. His rose-gold skin gleams. His black hair is perfectly coiffed. He wears a white and black striped fisherman’s sweater that clings to his body like a fawning lover. Legs crossed, leather pants on, the beauty of Rousteing is his simmering heat. Even through Zoom, his effect is dizzying; he is impossibly alive, full of an embodied electric resonance that beams. Inhaling his cigarette slowly, he leans forward and completes his thought.

“The problem with the old regime, the old fashion system, was that it was built on the premise that only a select few could access luxury. They were controlling the dreams of the people, manipulating their beliefs and what this does on a subconscious level is tell you that you have no right to imagine, it tells you that you are not even allowed to dream,” he said.

For more than a decade Rousteing has designed with the intention to defy fascist fantasies. In 2011, at the age of 25, he was appointed creative director of Balmain. The youngest creative executive of a luxury brand since Yves Saint Laurent, the pushback from the parochial and provincial Parisian elite was immediate. Questions that are too ignorant to repeat circulated within the industry questioning his youth, his hue, and his skills. Though he studied briefly at the prestigious Ecole Supérieure des Arts et Techniques de la Mode in Paris, he dropped out after six months and moved to Italy. There he worked at Roberto Cavalli, beginning as an assistant for creative director Peter Dundas, eventually moving on to design menswear and womenswear collections. In 2009, he moved back to Paris after being offered a job at Balmain. Working anonymously as a studio designer with Christophe Decarnin, in less than eighteen months Rousteing was at Balmain’s helm.

“Here in France, there is an allegiance to the past. We have a tremendous history, rooted in tradition, which is a beautiful thing but tradition, if you are not careful, can become a weakness. And when I first started very few people understood me. I cried a lot those days and there were many who tried to silence me, who kept demanding that I behave and not fight for what had not been done before me.”

His debut collection, Spring 2012 ready-to-wear revived old engines of decadence. With a visionary materialism that would’ve made the Ancient Egyptians proud, he deployed gilded mini dresses, ecclesiastical embroideries, and bejeweled blazers. Rousteing’s aesthetic was fuck-you-glamour, hieratic, and haughty, calling to mind the highest order of fashion: the long-forgotten griffe. More object d’art than mere outfit, each look was materialized perfection. Ungoverned by humility, unperturbed by sumptuary laws, long gone were the days of tattered jeans and shredded t-shirts. Within his first year, sales rose by 25%, reifying the house’s relevance in a new era.

In order to fully understand Rousteing’s aesthetic and the contention they caused one has to have an awareness of the European system of fashion. 19th-century German philosopher Georg Simmel suggests that “Fashion is a product of class distinction.” In his seminal text, “The Philosophy of Fashion,” Simmel argues that in order for fashion to exist society must be split between those perceived as inferior and those deemed superior. It is the “inferior one,” Simmel states, that “imitates their direct superior.” What this suggests regarding a country that has made illicit fortunes from a people’s enslavement is telling. Above all fashion is narrative, offering at best new networks of meaning and conversions of realities. Similar to the psyche in the dream state, with responsible hands, fashion as a system, as a network is capable of elevating consciousness, yielding new ideologies, and mobilizing futures. In destructive hands, fashion is despotic, historically and scientifically inaccurate, manufacturing massive uniformity and immuring imaginations.

Rousteing’s refusal to conform to such a system is rare. “Democratization has never meant you lose the dream,” he says, with disdain, eyes narrowing. “It means that you can welcome more people into your world, that you can share liberté and enhance your own understanding. I don’t care when it was, it’s never been right to alienate people because they don’t correspond to whatever stereotype the industry is willing to promote.”

It’s this allegiance to conscious craftsmanship that has kept Balmain light years ahead of the industry. Through Rousteing’s vision, each season has produced today’s trends. 2012’s Spring/Summer show skipped past sterile modes of power dressing and re-mounted classic, broad-shouldered silhouettes with dazzling diamonds. 2014’s Spring/Summer presentation rinsed off diseased nostalgia, restraining the excesses of ‘80s fashion. Rather than prop up some antiquated notion of aristocracy, Rousteing tapped Rihanna to lead the brand’s global campaigns. Before disingenuous displays of diversity became the rage, Rousteing was reproducing all the implacable shadings of daily life. His Balmain army, a cast of luminous Amazonian women, sent shockwaves down the runway. Not since the Battle of Versailles had such a showcase of multiculturalism made its mark. In 2015, diffusing styles across class lines, Balmain released a partnership with H&M which swiftly sold out. Two years later, before nearly every luxury house developed a beauty line, the brand released a cosmetics capsule with L’Oréal. The next year, before the NFT bust, Balmain launched a pre-fall campaign starring virtual models. Then in 2019, Rousteing introduced The Balmain Festival, an annual runway-concert celebration merging live music and film.

A self-defined “witness” of his time, Rousteing has no interest in resurrecting ghosts. Like the most forward-thinking scientist, his laboratory aims to inspire our collective evolution. A true Virgo, Rousteing refuses to rely on enormous reserves of talent or inspiration alone. Behind his surface glamour creeps an industrious rationality and methodical devotion. To stay ahead, Rousteing divides all of his collections into three corresponding units: aspirational couture, luxury price, and entry price. Each, he says adamantly, must flow.

“Balmain has an incredible history of craft. In today’s world, we need craft more than ever. But product is equally important. You must mix the two in order to sell. I have to translate all of the brand’s DNA into easier, less expensive, flamboyant offerings. You need the dream, but it must be concrete. If I didn’t have an affordable or entry price, I wouldn’t have the means to make my wild, unique pieces.”

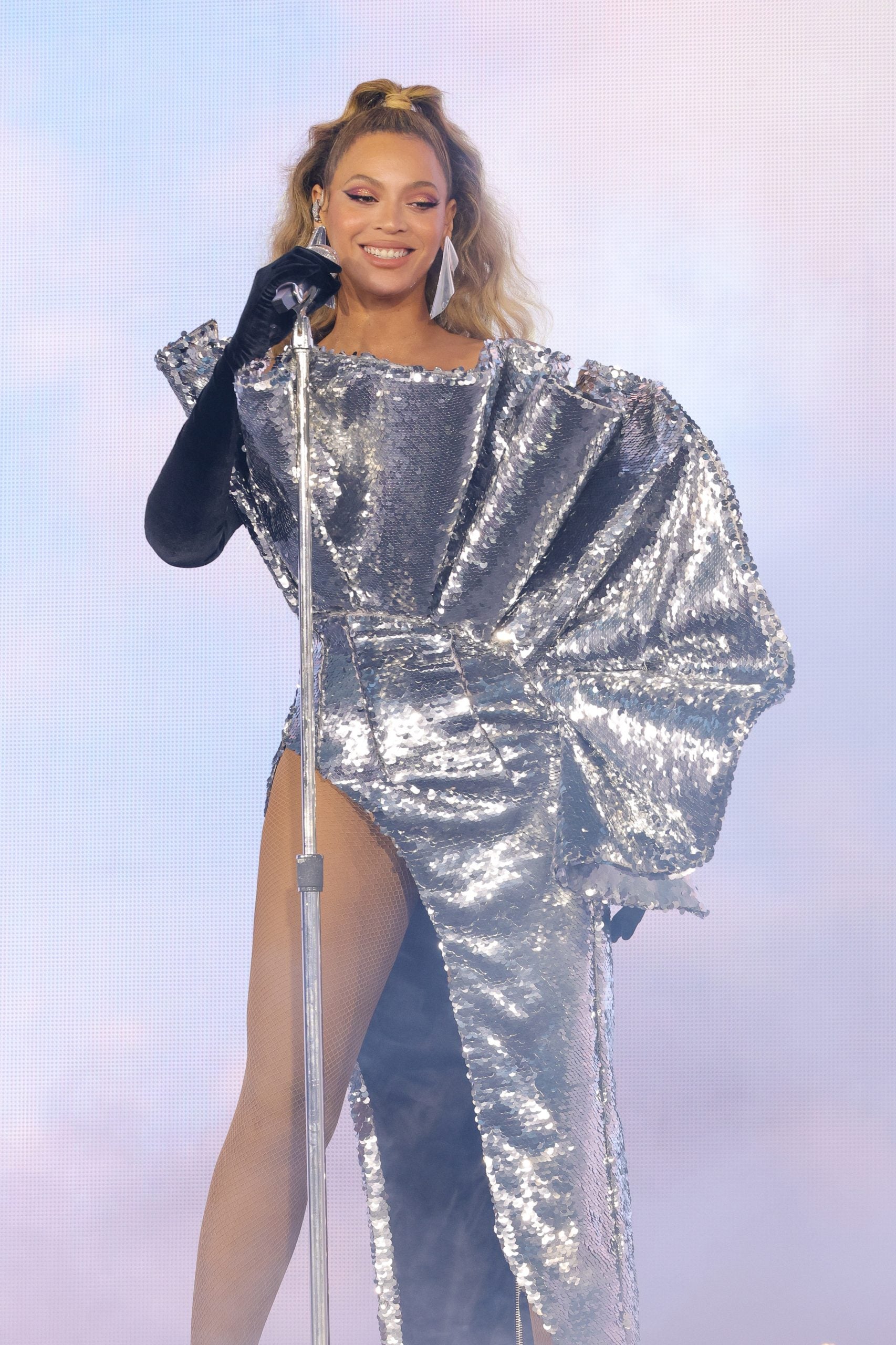

In March, Rousteing offered perhaps the most timely expression of unrestricted craft. Co-creating with Beyoncé, the two designed a 16-piece couture series titled “Renaissance Couture.” Modeled from songs from the album, the not-for-sale-collection flaunted past two-dimensional stylings and signaled to the higher cultures of Kemet, China, and Homeric Greece. For the final stop of her European tour, Beyoncé wore a custom metallic gown with a sequined sea-shell bodice and a dramatic slit; in Amsterdam, she wore a bee-inspired bodysuit that received its own standing ovation. Rousteing refers to Beyoncé as a “huge fighter of repressive systems,” an artist who signals that “freedom is the future.” Though he speaks highly of all his collaborators, one gets the sense that these are not cash-grab impulses but personal, thoughtful relationships. Shiona Turini, Julia Sarr-Jamois, KJ Moody and Karen Langley contributed as stylists for the fantastic and expansive Renaissance World Tour.

“What’s incredible to me is that I’ve been surrounded by incredible people who also want to shift the notion of what is luxury, what is aristocracy, what is fashion,” he says. “I’ve never believed in aristocracy, I believe in meritocracy. Your circumstances should never define you, good or bad, it’s important to break the codes of fashion.”

And yet breaking the codes may be synonymous with breaking the bank. Amidst a line of hair care products, a sustainable jewelry collection, and a formal beauty line launching early next year, Balmain continues to disrupt the cabals of beauty and fashion. Despite record growth and expansion, Rousteing’s measure of success has little to do with this material world.

“I’ve always worked for my generation and the next generation, so they don’t go through what I’ve gone through. I can’t measure success in dollars because it doesn’t match the purpose of life,” Rousteing adds. “It’s nice to have great critiques from the press or a sold-out collection, but there’s nothing more emotional for me than seeing the world expand, to open up perceptions, and bringing my community together. This is what makes me the proudest, this has always been my dream.”