It’s difficult today to singularly define what streetwear is, with its growing sphere of influences and origin stories. Currently, consumers and participants operate in a landscape that honors multiple narratives at once, at times deconstructing the use and futures of a marginally born fashion subculture in a late-stage consumerist industry. However, out of this debate comes the possibility for where it can go in the future. Some shared themes among many intentional practitioners streetwear culture are ideally, accessibility of form and community. Two Ohio-bred designers and brand-makers are trying to recenter those elements in a way that nods to their personal history of joint uplift.

James Drakeford and Dionte Johnson gained part of their fashion consciousness from the early era of brick-and-mortar sneaker and skate culture, when spaces were plentiful in their respective Ohio hometowns.

“I’ve been into streetwear since, I would say, middle school.” James Drakeford tells ESSENCE.com. “The event [we created] is more of a platform for brands, entrepreneurs, anybody that has some type of creative offering to get into this world.” Drakeford, who was born and raised in Dayton, Ohio made a personal commitment to spend more time on creative endeavors, particularly photography, after graduating from The Ohio State University. Today, Drakeford wears many hats as a Harlem-based professional photographer, fashion buyer, and the co-founder of Streetwear Flea, an endeavor created in an attempt to transfer the feeling of home to the oft-disjoined creative landscape many creative transplants traverse in New York City. The influence of Ohio’s sneaker and skate culture rings just as deeply as it did in his youth, and Drakeford works to maintain a connection to the Midwest designers who inspire him and the New York streetwear culture at large.

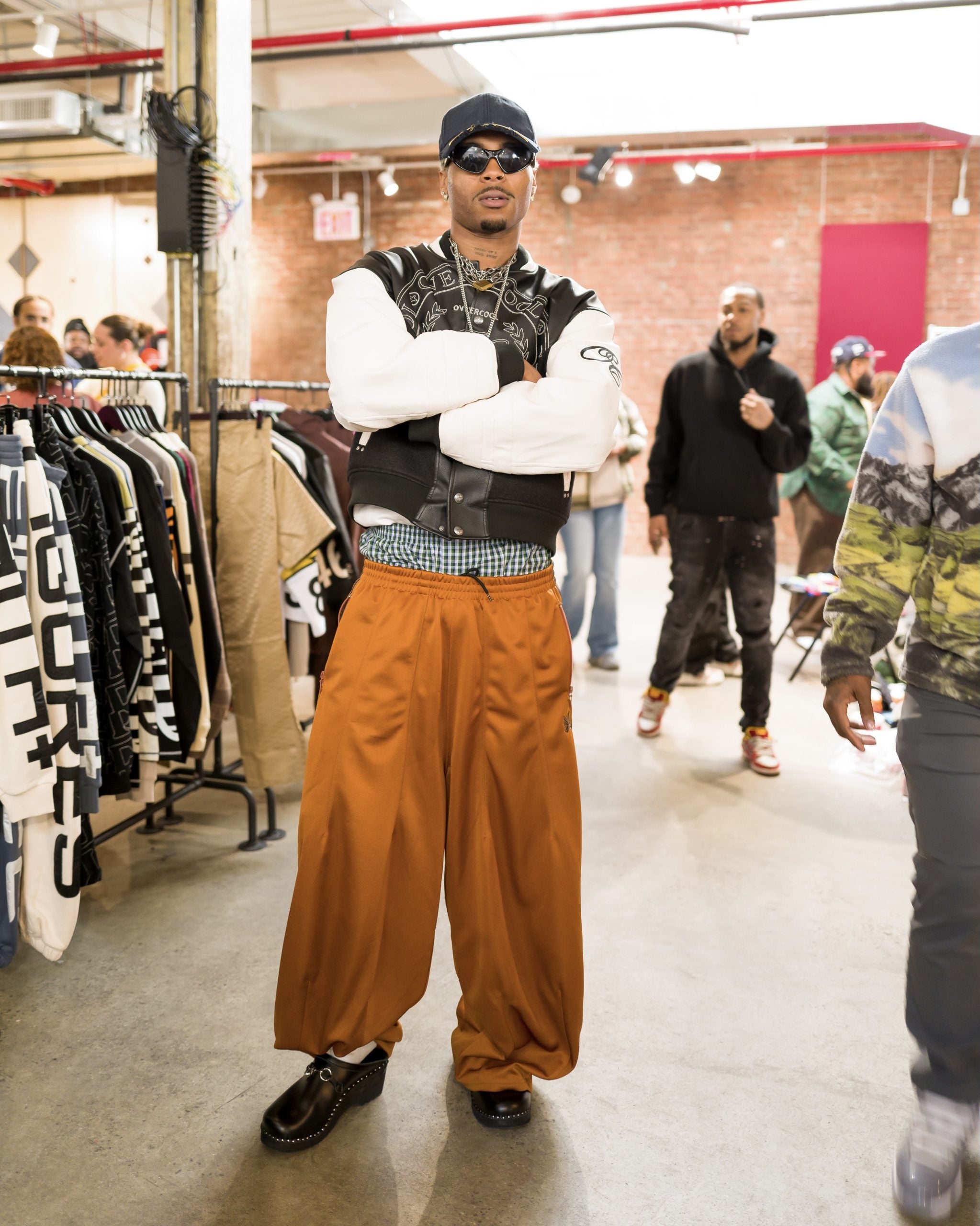

Streetwear Flea is less of a marketplace and more of a convention, which has grown through mostly word-of-mouth connectivity between brands and artists. In addition to showcasing work, there is a goal of meeting like-minded enthusiasts. Today, their programming takes place in New York, Austin, and Columbus. Vendors are hand-selected “by us for you,” according to the platform’s webpage. “We believe in a quality over quantity approach and want to give all attendees the best, most authentic streetwear experience.” Despite the sales component of the event, Johnson and Drakeford are adamant that this is not solely about a transaction—they are trying to recreate something they believe has gotten lost in the shuffle.

As streetwear has become more popular over the years and online shopping has rendered physical stores less ubiquitous with the cycles of hype and aspiration. The housing crisis of 2008 created a long-term impact on the nature of property ownership, causing many hopeful shop and label owners to stick to a strictly digital format that lessens the overhead of operating a permanent space. While a whole new world of streetwear and shopping at large has been able to flourish, the community element of shopping at large has become rarer. The mechanisms of making money just are not the same anymore.

The magic of what they’ve created is that for a time, visitors can forget the structural challenges of the field and convene under a shared love of craft. It is all the more important because of the shifting of community representation, as streetwear, like hip-hop, was established through the cultural collaborations of marginalized Black, brown, and other POC communities. The aspect of close-living—of neighborhoods and meeting more people offline—is what is missing from streetwear today. Both Drakeford and Johnson feel this is notable and why they aim to fill this gap.

Reflecting on his childhood sneaker and skate stores, Drakeford describes them as sites of convening. The shopping, though technically central, was never the only point. The nature of collecting people under a shared niche interest was a baseline to build outward and upward. He expresses that in Columbus, Ohio there were sneaker shops and skate shops where sneaker enthusiasts could network and build relationships. These spaces were niche communities that were important to him.

Drakeford elaborates that the internet has streamlined the shopping experience, but has also made many aspects of the industry uniform. “Back then, because the same things weren’t all accessible online, you had to go to a lot of stores to get specific products. You had to see people, you had to speak to people because everybody couldn’t just do it from the comfort of their phone,” he notes.

The invention of this project, especially as it grows in different cities and touches multiple regions’ legacy of this storied avenue in fashion history, the Johnson-Drakeford duo hopes to demonstrate what they learned from the previous era: we all need people.