The objection of Virgil Abloh when it comes to his space in Black conversation is often loud and untenable.

This idea that he has democratized his Blackness has at times muddied the popular view of him. Aware of the critiques that often surround him, Virgil Abloh aims to take back that narrative. Louis Vuitton’s Fall 2021 menswear show was an emphatic note to self.

Narrated by spoken word artist Saul Williams, the collection is informed by James Baldwin’s “Strangers In The Village” essay. In the essay, originally published in 1953, Baldwin declares that, while he is a stranger in the village of Leukerbad, where he is staying, he also feels like a stranger in the village of the United States. This essay sets the pace not only for the environment in which the collection is displayed, but the collection itself. It is a statement of Virgil’s place in fashion, as the first Black Artistic Director of Louis Vuitton. And his place within our community.

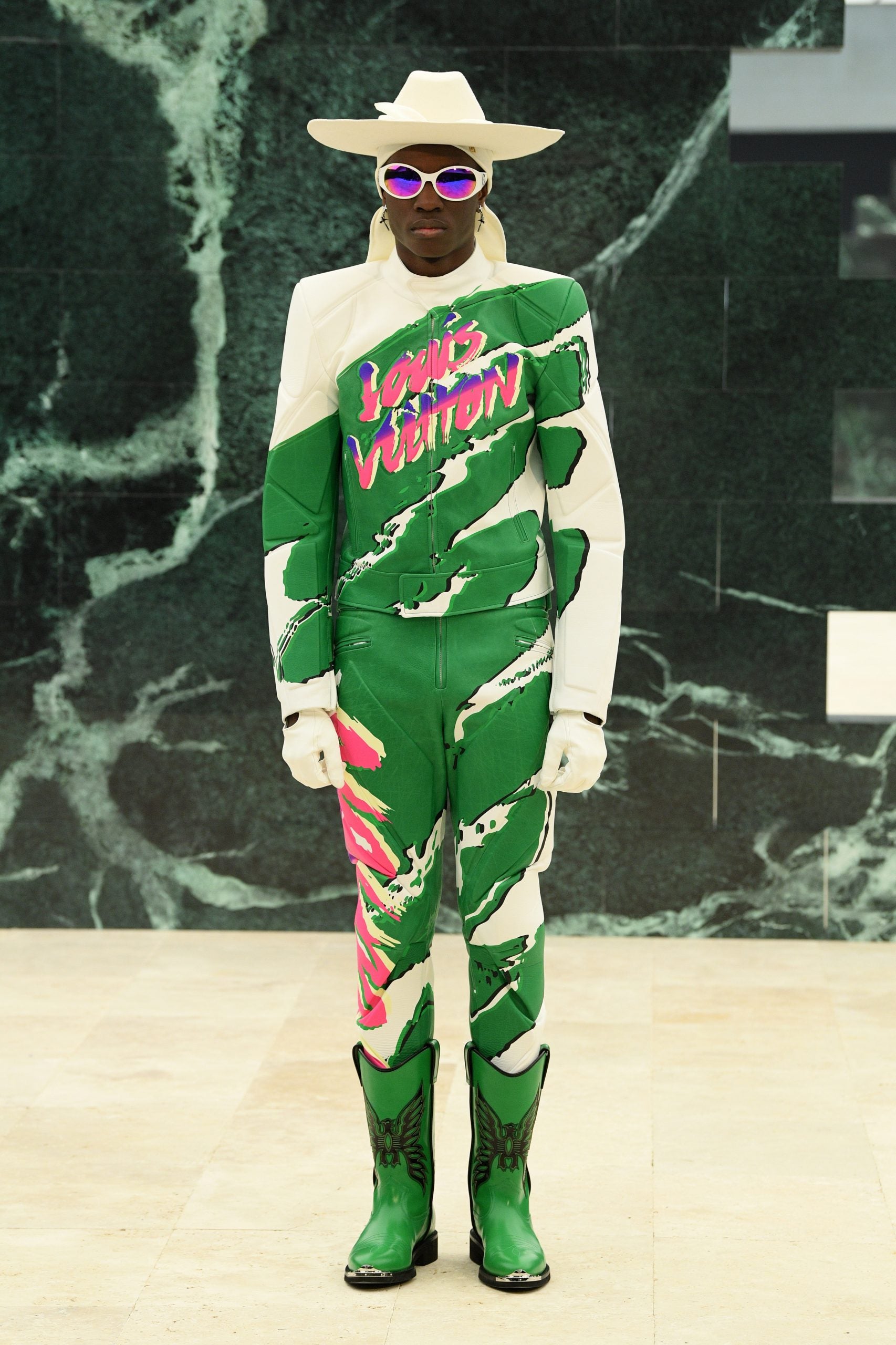

Abloh affirms that though we are worlds apart, Black communities often share similar experiences: similar grief, similar rage, and similar joy. That feeling that sits itself atop your gut when you feel you do not belong. It is that familiarity as Black people that we have with each other that is embedded into the fabric of this collection. Abloh has often been criticized for his inability to connect with us. The general consensus was that he was not one of us. In fact, critics believed that he had traded his Blackness in for something more shiny, polished and palatable. Seemingly, he did not grieve with the community as we continued to suffer great losses. In a presentation directed by Wu Tsuang, performed by Yasiin Bey and the stylings of IB Kamara, who has been key in Abloh’s storytelling, the collection entitled “Ebonics” seeks to explore “the presumptions we make about people based on the way they dressed: their cultural background, gender, and sexuality”, Virgil Abloh crossfades several cultural attributes surrounding the way one should dress, or be represented.

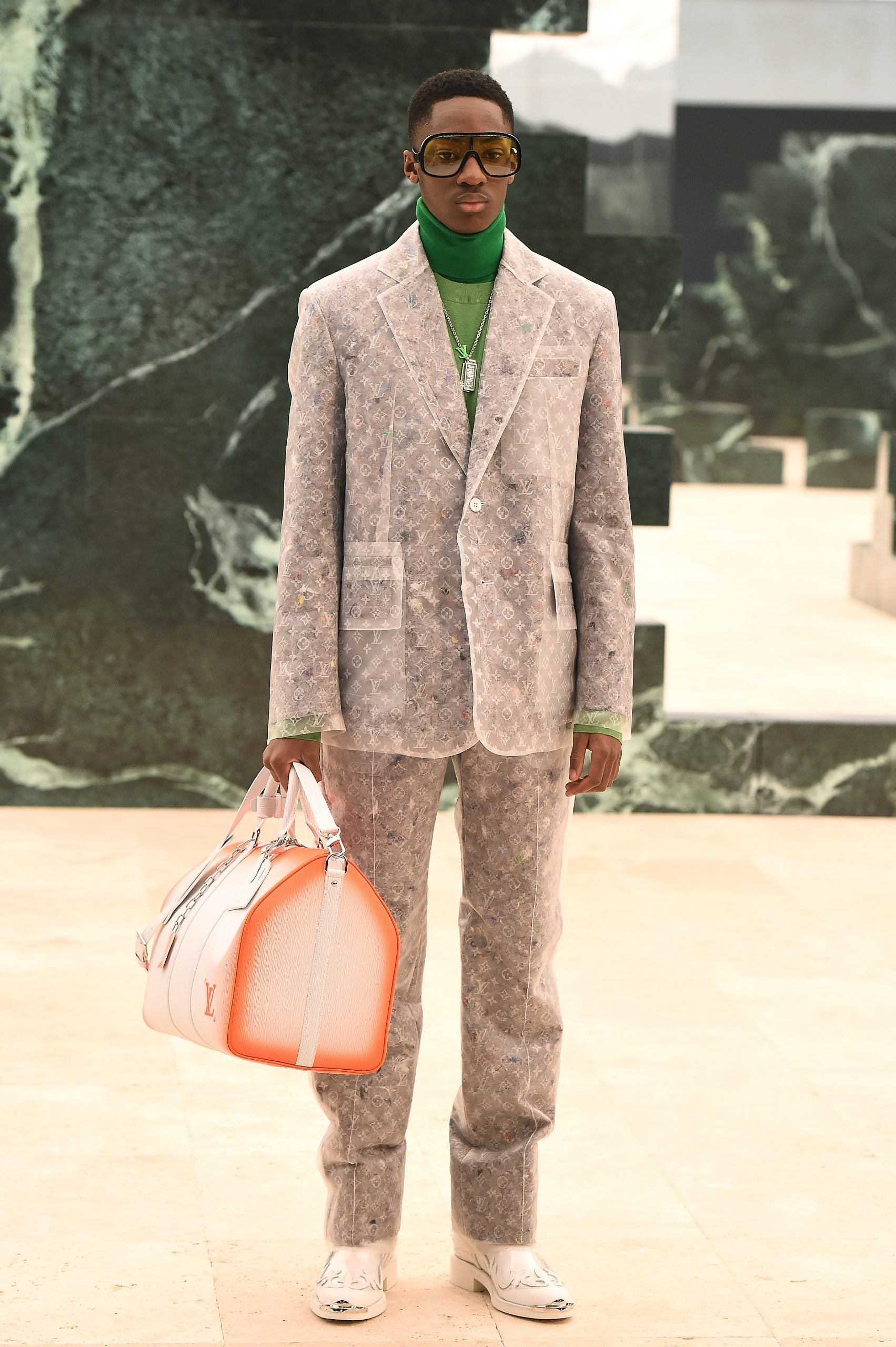

There is no question that the collection feels Black. Rich in both culture and texture, is not devoid of context nor does it ever feel as if Blackness has been put in quotations. Focusing on beautiful textile work reminiscent of the eclecticism and vibrancy of traditional Ghanaian Kente, never has Abloh’s own culture been more apparent. The addition of Louis Vuitton‘s signature motifs throughout create a stunning display of tradition and commerce, emblematic of the Abloh brand. Of the collection, Abloh says, “Within my practice, I contribute to a Black canon of culture and art and its preservation.”

With preservation comes a responsibility to elevate our image. Abloh succeeds. The very essence of the collection speaks to Blackness all over the diaspora. A Black man on the move, yet acutely aware both socially and consciously of his surroundings. Not seeking awareness in the sense of seeking to conform, or to submit, but rather to be highlighted. We learn that even through our collective repudiation, we can reconcile. That Blackness is not yours, it is ours.

If fashion is the medium in which Abloh chooses to speak, then he has said something worth hearing. In a collection that will surely define what is next for the designer, who, born to Ghanian parents, and raised outside of Chicago, is no longer a stranger in the village that Louis Vuitton created.