Last year Kim Kardashian West made headlines when she used her star power to help get several people, including Alice Marie Johnson, released from prison. What many failed to realize is that Johnson also had a team of Black women working in her corner. “Kim definitely used her platform to highlight the conditions and policies that put women like Alice Johnson in prison,” attorney Brittany K. Barnett says. “I think our complementary efforts are necessary to drive impactful change, but everyone has to be responsible in those situations, too, when it comes to knowing what is really happening.”

Barnett was referring to the ubiquitous headlines that spoke of “Kim Kardashian West Freeing 17 People From Prison.” Behind the headlines, it was Barnett, along with West’s attorney Shawn Holley, who toiled long and hard in the trenches. “No one’s reading the article to see that Kim Kardashian West helped to partially fund the campaign of two Black woman lawyers who actually did the work to get those people out of prison,” Barnett notes. “That is problematic. I’ve never done this work for credit, but I do feel it’s important for little Black girls to see that two Black woman lawyers are doing this work.”

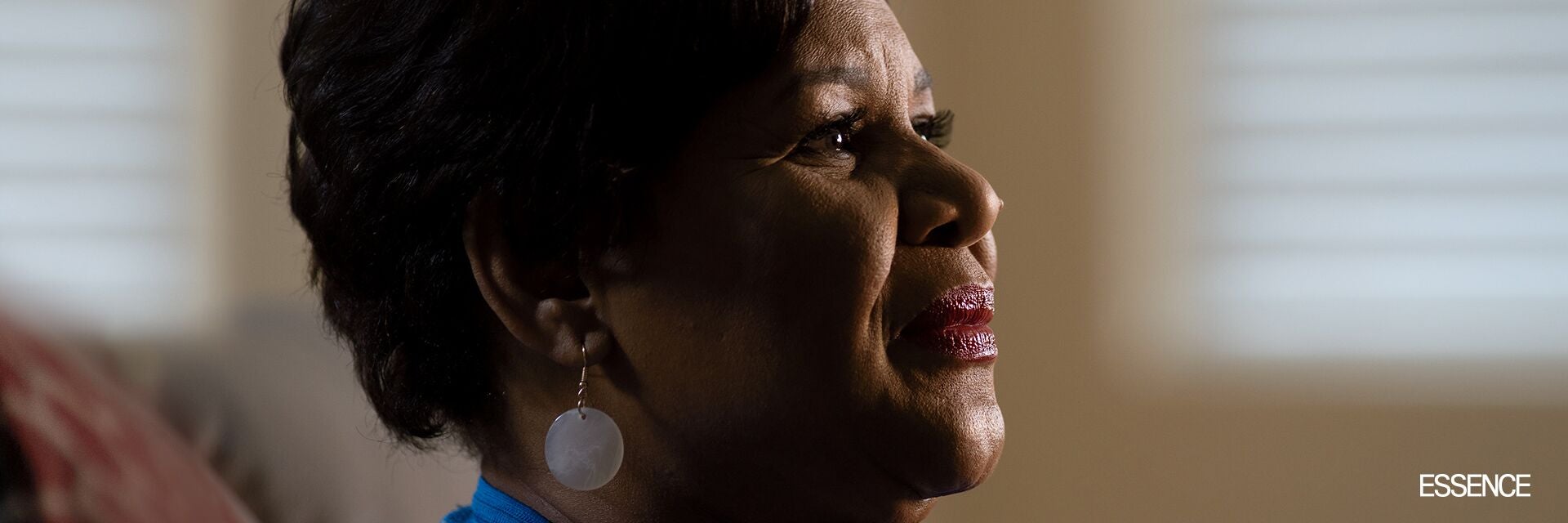

Johnson certainly appreciates the hard work Barnett and Holley put in on her behalf. Born in 1955 in Cockrum, Mississippi, she was the sixth of nine children in a Christian sharecropping family that was being exploited by the landowner. “We picked cotton, we chopped cotton, and every year my parents would hope for a good crop so that we could move up north,” Johnson recalls. “That was the dream of most southern Blacks—to one day move up north, like it was some type of promised land.”

Her parents eventually bought a home and moved their family under the cloak of darkness. “It was like a scene from Roots,” Johnson says. “Literally, I had a hand over my mouth as I was loaded into the car with my siblings. It was like we were escaping slavery, but we weren’t. It was around 1960 or 1961, and that was the beginning of a new life.” As it happened, that new life had its own challenges. At 15 Johnson, a newlywed, became pregnant and was having difficulties navigating the school system, her impending motherhood and a tumultuous relationship.

Although Johnson went on to graduate from high school, her marriage remained troubled. “My husband was the only man I had ever dated, so I didn’t know anything about really living,” she says. In 1979, after 19 years of marriage and four children with another one on the way, Johnson left her husband and moved to Memphis. The young mother and estranged wife struggled at first and found herself in need of government aid. Things began looking up when she landed a job at Federal Express. But after reconciling briefly with her husband before leaving him again, Johnson lost her job and filed for bankruptcy.

“I was desperate,” she remembers. “I got a factory job, but it didn’t pay nearly enough to sustain us. At the time I had one daughter in college and another one about to go to college.” With no financial support from her ex-husband, she began to panic. She decided to take a family member up on an offer that, in hindsight, she should have ignored.

“A relative from out of town asked if I knew anyone in the drug business,” she says. “That was crazy to me. Why would she even ask me something that crazy? She was with her husband, and they were visiting my house, and I guess they saw the desperate state that I was in; I was trying just to keep my utilities on.” The relative explained how she could earn some money off the books without ever having to physically touch any drugs. All she had to do was use her telephone to connect the supplier with the dealers. “I never sold or used drugs,” she says. “I would just pass phone numbers.”

For three years Johnson participated in the drug conspiracy until she was arrested and eventually indicted. During those three years, she had planned to stop participating in the business, but before she could make her exit, her youngest son was killed in a motor scooter accident. On the day of the accident, she received a phone call that would later affect her indictment.

“My cousin was married to a Colombian, and she lived in Colombia with him,” Johnson says. “And the day that my son was killed, she called my house. The news had gone through the family that my son had been killed, and she called [to offer condolences]. But that one call from Colombia would be used against me at my trial. They said that it was [proof of] a Colombian drug connection.” A year and a half after her son’s tragic accident, the feds came knocking at her door.

“The investigation actually started in 1993, but they arrested me in 1994,” she says. “They called me for questioning right as the indictment was about to come down, and they tried » to get me to cooperate and become a witness for them.” Even with threats of arrest, Johnson refused to cooperate with the feds. They turned up the pressure on her and her family and eventually arrested one of her daughters as well.

According to Johnson, she was originally offered no jail time in exchange for her testimony implicating others, but after her arrest and that of her daughter, she was charged with attempted possession, money laundering and money structuring. Although Johnson was out on bond for two years, she was sentenced to life in prison plus 25 years after a six-week trial.

As with many inmates entering the prison system, Johnson was subjected to degrading and dehumanizing experiences that included body cavity searches. All she could think of was, Is this going to be my final resting place? Is this where I’m going to die? “I was told that I would take my last breath in prison,” she says.

After years spent trying to appeal her sentence, she resorted to a last-ditch effort to regain her freedom. She filed several petitions for clemency with President Barack Obama. Even though she was denied several times, Johnson wasn’t easily dissuaded. Not only did she continue her fight but she also helped other women in prison file similar petitions, and she began to make use of technology to get her story heard.

“I started speaking on platforms from inside of prison,” she says. “I spoke at Yale University, Hunter College, New York University, the University of Washington in Seattle. And I was on Google and YouTube platforms, too, on video. It’s like Skype. I was speaking to the outside public even though I was locked up.” One of Johnson’s videos eventually went viral after it was shared by criminal justice advocate Topeka Sam, who had previously met Johnson through the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls. It was that video that would catch the attention of Kim Kardashian West.

“She heard my story, and she said, ‘This is so unfair.’ And she contacted her attorney, Shawn Holley, who contacted me and told me that a rich and famous woman wanted to be my benefactor. I thought it was Kris Jenner. I didn’t even know who Kim was,” Johnson admits.

But even before West came on board, Brittany K. Barnett was on the case, trying to get Johnson released from prison. “She was already working, trying to help me, because she had got my best friend, Sharanda Jones, out,” Johnson states.

Over the course of seven months, West’s team of lawyers, Barnett, presidential senior adviser Jared Kushner and other legal professionals worked on securing Johnson’s freedom. Holley and West met with President Donald Trump on May 30, 2018, and by June 6, 2018, Johnson, now 63, had run into the arms of her family after being released from prison. She was later honored at the State of the Union Address on February 5, 2019, as an example of sweeping prison reforms.

It’s been a little over a year since Johnson’s release, and with the passing of the First Step Act, thousands of incarcerated people are returning to their families as the conversation around criminal justice intensifies. Although Trump may take credit for the passing of the act, Barnett offered insight on the law and its origins. “The First Step Act is a watered-down version of President Obama’s Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which he tried to get passed for years and years, but he was literally obstructed by Congress,” Barnett explains. “President Obama began doing this mass push for clemency because the bill wouldn’t get passed. There was desire for change under Obama, but there was no willpower from Congress. That was the difference between then and now.”

When it comes to West using her celebrity power to push Johnson’s story forward, Holley wants people to know she wasn’t in it for attention. “It’s hard for me to understand how anyone could find anything negative to say about her,” Holley says. “She was determined to get Alice out of prison, and she did.” Holley adds that although Trump did help secure Johnson’s release, that doesn’t mean she agrees with his politics. “I definitely have many, many disagreements with things that the Trump administration had done up to that point and has done since then,” she says. “But there is nothing bad that we can say at all about the fact that he granted our request and set Alice Marie Johnson free.”

Johnson, who says her motto is “If you can do good, do it,” is grateful for the help she received from West, and she’s also spoken about the role Trump played in her release. “You don’t care which way you come out of prison. You just want out,” she says. “And so we’ve got to put aside any political differences because this is not about politics. This is about people.”

Today, as Johnson readjusts to life outside of prison, she believes criminal justice reform work still has a long way to go. But she feels her life story can be a lesson to others. “Mine is not just a story about prison,” she reflects. “It is a story about a human being, about an ordinary woman who was caught up in something but didn’t allow it to defeat her. It’s a story of grace and mercy and redemption and second chances—a story I believe we can all learn from.”

Shaka Senghor is the author of The New York Times best-selling memoir Writing My Wrongs: Life, Death and Redemption in an American Prison.