Michelle Kenney speaks with the intensity of a woman training her grief to stay busy so that it doesn’t break her.

If it did, though, there’s not a human being with a heartbeat that wouldn’t understand.

It’s been over 500 days since then East Pittsburgh police officer Michael Rosfeld—a rookie who had only been sworn in hours before—fatally shot Kenney’s 17-year-old son Antwon Rose II.

On June 19, 2018, at approximately 8:30 p.m., Antwon and his friend Zaijuan Hester, then 17, caught a jitney to nearby North Braddock. Hester rolled down the back-passenger window and fired several shots at Thomas Cole Jr., who was standing on the corner, striking him in the abdomen. William Ross, who was standing next to Cole, was hit in the leg with shrapnel. The jitney driver fled the scene as one of the men returned fire.

Rosfeld was on patrol nearby when he spotted the light-colored Chevy Cruze carrying Antwon and Hester, which matched the description of the vehicle involved in the drive-by shooting just minutes before. The officer conducted a traffic stop and both teens fled. Hester got away without injury, but Rosfeld shot Antwon, who was unarmed, hitting him three times in the back, arm, and face.

Kenney’s baby was pronounced dead less than an hour after the shooting. And it’s been less than 300 days since a Dauphin County jury deliberated for less than four hours before finding Rosfeld not guilty of criminal homicide. They did this despite Rosfeld’s conflicting accounts of the shooting, first claiming that he saw unarmed Antwon with a gun, then retracting that statement. They reached this verdict despite the fact that, under Pennsylvania law, police officers can only shoot a fleeing suspect if that suspect poses an immediate threat, possesses a lethal weapon, or has previously used or threatened lethal violence.

Conversely, Allegheny County Common Pleas Judge Anthony M. Mariani told Hester, now 18, that his “risk to the community [was] substantial,” and sentenced him to serve six to 22 years in state prison. Apparently, white police officers are redeemable in ways that Black boys never are.

“I understand over the course of my young life, I made some mistakes,” Hester told the court during his sentencing hearing. “I am deeply sorry for my actions — because my actions cost my friend his life. I haven’t been the same since.”

Neither has Kenney.

A Mother’s Grief In Action

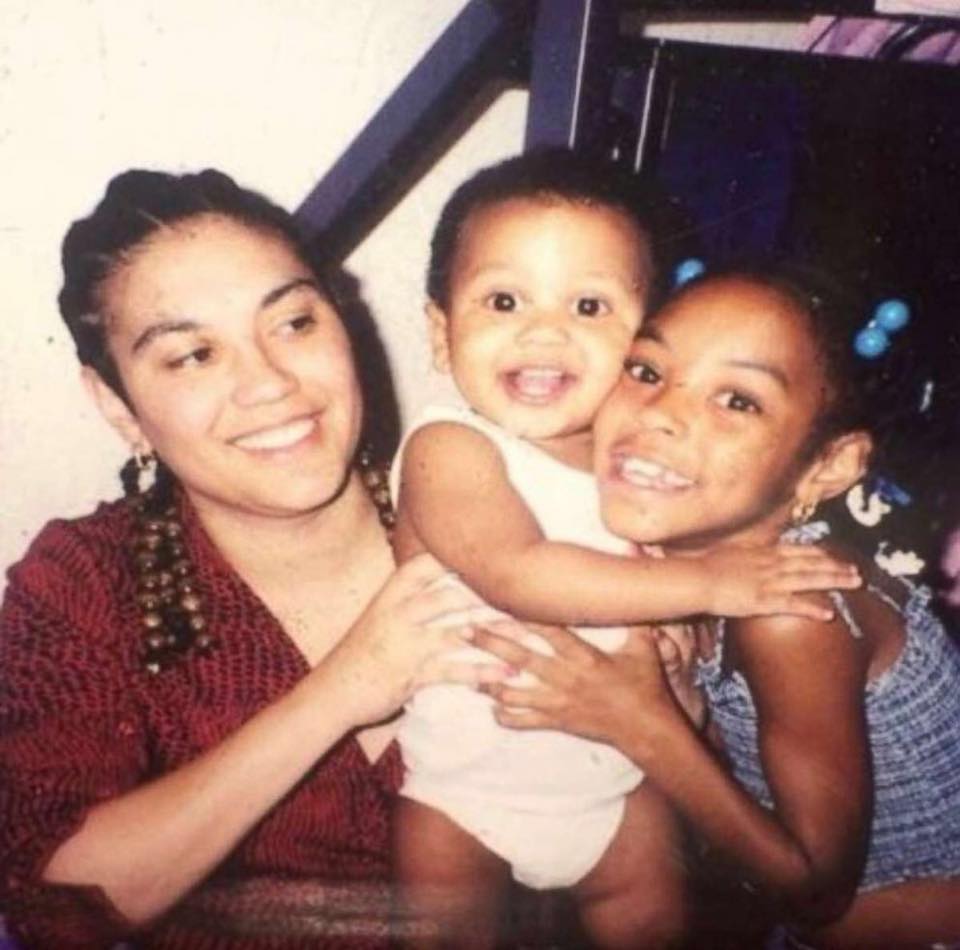

“I’m still standing, still fighting, still pushing,” Kenney tells ESSENCE. “But I miss my son. My daughter Kyra is missing her brother, her best friend. I’m still showing up in the schools, still doing whatever I can do to prevent someone else from having to walk in my shoes, all because of a kid deciding, in one split second, to hang out with any individual other than those that they know well.”

Committed to making the world a better, safer place for Black children, Kenney is fighting to ensure those police officers sworn to protect the communities that they claim to serve are mandated by law to use non-lethal force and de-escalation tactics before shooting suspects.

Earlier this year, the grieving mother joined forces with Pennsylvania state Reps. Summer Lee and Ed Gainey to introduce House Bill 1664 to the Pennsylvania General Assembly. The Bill states that a peace officer is justified to use “reasonable” force deemed necessary to effectuate an arrest, and “reasonable” force deemed necessary to defend himself or others from bodily harm. It further states that an officer is justified in using deadly force only when he “reasonably” believes that such force is necessary. If the bill passes, “reasonable” will replace “any” in Pennsylvania’s use of force laws.

“I thought I had to protect Antwon from the streets. I didn’t know that I had to protect him from the police.”

Even as protests rocked the city in support of her son, Kenney was always concerned about another mother sharing her fate.

“We live in a system of good ole boys. It doesn’t matter what side these officers claim to be on in public, behind the scenes, they’re all on the same side,” Kenney, who previously worked in a police department, shares with ESSENCE. “There were people in the city who supported this officer shooting my son in the back. Some of those police officers still work there ‘til this day,” she continues, the frustration evident in her voice. “I know Antwon’s friends and classmates wanted to support him, but I was afraid that someone else’s child might die if they took to the streets and protested.”

First They Kill You; Then They Kill Your Character

Kenney has not only had to deal with her baby boy’s physical death, but the attempted assassination of his character. An honor roll student at Pittsburg’s Woodland Hills High School, Rose was in Advanced Placement classes and volunteering in his community when Rosfeld killed him. None of that mattered in the end, Kenney said—not when Rosfeld fired at her baby, and not in court, when his attorneys were defending his right to do so.

“For years, I would watch mothers in this same situation. And I always said, ‘My heart breaks for them; I don’t know what I would do,’” Kenney says. “And now, guess what, I am them. It happened. I‘ve had to protect and defend my son’s reputation every day since his death in a way that I never had to do when he was living.”

“They can stop playing with me coming for my son.”

“I had hundreds of people telling the world how kind my son was, how giving he was, and how he was never in the streets like that,” Kenney continued. “He wasn’t there to defend himself in court; nor, was he there to tell us what happened that day. And people created their own stories, including the DA’s office. They can stop playing with me coming for my son.”

Moving Forward, Even When It Hurts

Kenney is often asked about her advocacy work and what she would tell other Black mothers as she navigates debilitating grief and the most unspeakable pain. For her, the answer is as simple as it is complicated.

“I don’t know what to tell them,” Kenney said quietly. “There’s no answer that I could give that would be guaranteed to save someone else’s child. I put Antwon in activities. I put him in counseling. I waited for him on my porch until he got home from volunteering. I walked up the street. I told certain people in the neighborhood to stay away from him. I laid down the rules. I did everything, all the things, I thought a Black mother could do, should do, to protect her child.

“And it breaks my heart because it wasn’t enough,” Kenney said, tears in her voice. “My son wasn’t murdered because of something that someone thought he did. Antwon was murdered because he was a Black kid who ran from the police. He was convicted when he was lying on the ground, bleeding out, in handcuffs. My son was convicted of being Black while he was face down in the dirt, gasping for breath, dying.

“I thought I had to protect Antwon from the streets. I didn’t know that I had to protect him from the police,” Kenney continued, her voice breaking. “And I hope Michael Rosfeld sees my son’s face every time he wakes up, and every time he goes to sleep.”

“I Am Not What You Think!”

I am confused and afraid

I wonder what path I will take

I hear that there’s only two ways out

I see mothers bury their sons

I want my mom to never feel that pain

I am confused and afraid

I pretend all is fine

I feel like I’m suffocating

I touch nothing so I believe all is fine

I worry that it isn’t, though

I cry no more

I am confused and afraid

I understand people believe I’m just a statistic

I say to them I’m different

I dream of life getting easier

I try my best to make my dream true

I hope that it does

I am confused and afraid

—Antwon Rose, 15-years old, May 16, 2016

Kenney continues to try to make sense of her new reality without her baby boy—a child who loved his mother, and his sister, and his niece. A community leader who loved his friends and wanted to change the world. A boy, a beautiful Black boy, whose death has created a void that nothing, or no one else, can fill. Even in the midst of Kenney’s grief, her purpose is clear.

“In my mind, I don’t have a choice other than to keep fighting,” she said with conviction. “That’s my son. These are our children dying out here. So, I’m not letting go, or letting up, until I die.”