When one mentions the name Bryan Stevenson in social and criminal justice spaces, it is met with reverence and respect.

Stevenson, 59, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative based in Montgomery, Alabama, has been in the trenches and at the front lines in the fight against the death penalty. He has argued five cases before the United States Supreme Court and, through EJI, has won reversals, relief or release from prison for more than 135 wrongly condemned death-row inmates, people abandoned by society at-large and left to die in cages.

The veteran attorney, author, and freedom fighter’s life’s work is featured in a new HBO documentary, True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality. A film adaption of his book, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption, will hit theaters in December 2019, with Michael B. Jordan starring as Stevenson and Jamie Foxx starring as Walter McMillian, who, in 1987, was sentenced to death after he was wrongly convicted for the murder of an 18-year-old white girl.

Stevenson took on McMillian’s case in post-conviction, where he showed that the State’s witnesses had lied on the stand—and that the prosecution had illegally suppressed evidence. The case was overturned by the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in 1993 and McMillian was released after spending six years on death row for a crime he did not commit.

In an interview with ESSENCE, Stevenson’s voice is filled with the echoes and expectation of victory, despite the pain he has seen and the horrors he’s witnessed.

“We, in the African American community, have always known that the criminal justice system is a threat, that it will take people who are innocent or wrongly convicted and it will treat people unfairly,” Stevenson responds when I ask him about the awesome responsibility of holding life and death in his hands against the gravitational pull of injustice. “But we keep fighting.”

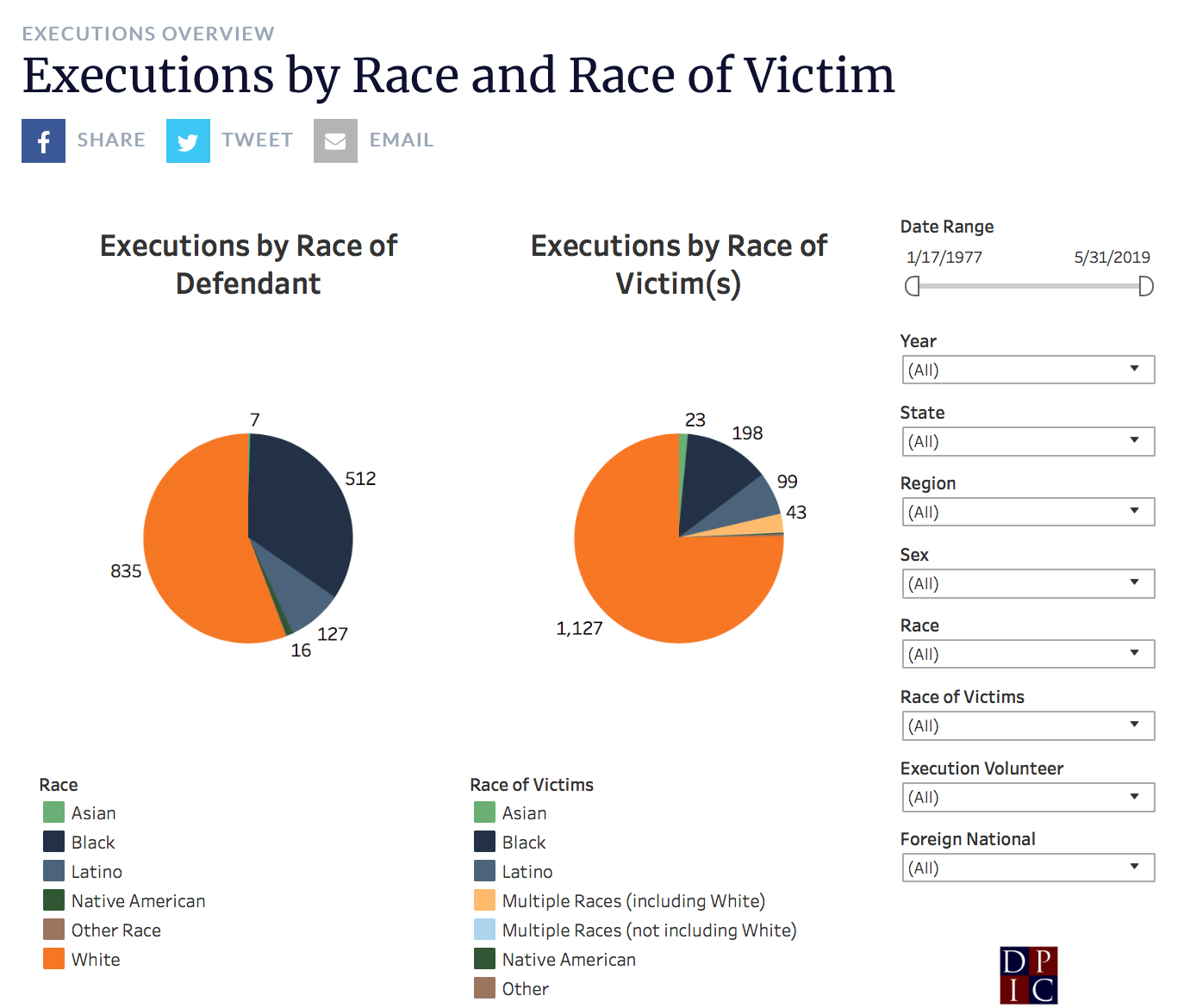

According to EJI, more than half of the people on death row in this country are people of color. Of the more than 2700 people currently under a death sentence, 42% are Black, 13% are Latinx, and 42% are white, despite Black people making up approximately 13% and Latinx people making up approximately 18% of the population, according to 2018 census data.

Additionally, nearly 80% of murder victims in cases resulting in an execution have been white, even though nationally only 50% of murder victims are white, i.e. those who murdered white people were found more likely to be sentenced to death than those who murdered Black people, according to DeathPenaltyInfo.org.

“It’s been really difficult to get the rest of society to acknowledge the racial disparities and inhumanity within the criminal justice system,” Stevenson continued. “But I’ve been laboring at this for a really long time, and I feel hopeful about this moment, despite the challenges that we face.”

This moment is, indeed, rife with both cruelty and resistance. As ESSENCE previously reported, Attorney General William Barr announced in July that the federal government will be resuming capital punishment after 16 years. One day later, Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) announced that she would be introducing a bill that would “prohibit the imposition of the death penalty for any violation of Federal law, and for other purposes.”

Pressley announced the bill on social media, tweeting, “The same #racist rhetoric coming from the occupant of the @WhiteHouse, who called for the execution of the #Exonerated5, is what led to this racist, vile policy. It was wrong then and it’s wrong now.

“The cruelty is the point – this is by design.”

For Stevenson, this nation’s failed promise of “with liberty and justice for all” is what compelled him to enter the legal field.

“I became a lawyer because I really did want to have the skills and abilities to get behind the limitations of democracy,” he said with conviction. “I grew up in a community where the Black kids had to go to the ‘colored’ school and if you left it up to people voting whether or not to end racial segregation in schools, because white people were the majority, that would have never happened.

“It took the rule of law and the ability to go into a courtroom and make things change,” Stevenson continued. “And that’s what motivated me. I always want to use that power to help people who are disfavored and disadvantaged, to help people like the people I grew up with.”

From George Stinney Jr. To Troy Davis

George Stinney Jr., the youngest person executed in the U.S. in the 20th century, was only 14-years old and weighed 95 pounds when he was accused of murdering two white girls with a railroad spike in 1944. His trial lasted for less than three hours and an all-white male jury deliberated for 10 minutes before returning a guilty verdict. Though a South Carolina judge exonerated young George in 2014, ruling that there had been “fundamental, Constitutional violations of due process,” the evilness of George Stinney Jr.’s state-sanctioned execution is haunting. His photo appears in the early moments of True Justice.

“The spectacle of putting a little boy on top of Bibles so his head would be tall enough for the electrodes to reach, then to kill him and go home like you’ve done something right or just, and not be overwhelmed by that illustrates the perversity of what this system can do,” Stevenson says quietly.

Though Troy Davis, at the age of 42, was much older than George Stinney Jr., when the state of Georgia killed him by lethal injection in 2011 for allegedly murdering a police officer, the spectacles of their executions further expose the ugliness this nation tries to conceal with flag-waving and anthem-singing. Davis was not proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Frantic efforts to save his life reached all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in the 11th hour, but to no avail.

“Continue to fight this fight…,” Davis said to his loved ones gathered to watch him die. He also addressed his executioners. “For those about to take my life, may God have mercy on all of your souls.”

For Stevenson, it is important not to view these cases in a vacuum—and equally important to be clear on one thing.

“We don’t have to execute people in this country to keep the public safe,” Stevenson said. “Like with Troy Davis, if there’s a question about guilt, then why execute the person? Why? There is a parallel between those two cases that I think is important for people to recognize.”

With Justice For All

Despite the miscarriages of justice Stevenson has witnessed and experienced throughout his career, he still believes in equal justice under the law. This struck me as the familiar well-worn, tattered, beautiful Black southern faith that got our elders and ancestors through, mixed in with that same steely determination that says if it’s not so, yet, then it will be when we’re done.

And while that is certainly admirable, there was a time when the Deacons for Defense and Justice walked the walk of armed resistance during the same decade that Malcolm X taught that there had never been a revolution without bloodshed. And as Princeton Professor Eddie Glaude recently made plain, we’re living and loving and fighting through a cold Civil War right now.

So, does Stevenson believe—with all that he’s seen—that freedom and justice for all can truly be found inside of a courtroom and through non-violent protests? Will revolution truly come from inside of the system—a system that is not broken, but functioning exactly as intended? As James Baldwin once asked, “How much time [does this nation] want for [its] progress?”

“Violence is not just something that you do to other people; in fact, it does something to you, as well,” Stevenson responds with the conviction of a man who has thought this through many times. “And I’m not willing to give away my decency and my humanity and my capacity to love—which is what my mother and my grandmother gave to me, and her mother and our enslaved ancestors gave to them.”

“The people who shaped me are the people like my grandmother and my mother. These women had such strength and wisdom and insight and tenacity–and they were courageous when other people were quiet. Johnnie Carr and Jo Ann Robinson and Claudette Colvin and all of these women who were the real architects of the Montgomery Bus Boycott and made the Civil Rights Movement succeed. We have to honor and recognize them.”

Bryan Stevenson

Stevenson then recalls a conversation with freedom fighter and civil rights leader Rosa Parks, during which she was very specific in telling him to be brave—not fearless, but brave—as he continued his fights for justice.

“I think [Parks] knew that it would be irrational to be fearless,” he tells ESSENCE. “I’ve been in situations that I’ve been very worried about how we’re going to be victorious, but I think of our people, our history. The enslaved people who escaped, who took the Underground Railroad.

“Then I think about the people who didn’t escape, who still found ways to love their children and create joy, even if that was tenuous and they weren’t sure if they could hold on to it,” Stevenson continued. “I think about the Black people who fled the American south for the north and west in response the violence of lynching and terror. Then think about the Black people who stayed despite that threat and terror.”

For Stevenson, that ancestral resilience that has been passed down through generations of Black people not only gives him strength to fight for freedom even on the days that all seems lost, it also reminds him of his responsibility to pass the tradition on.

“That’s the legacy of our community, this capacity to stand up when other people say sit down, to speak when other people say be quite,” he says with palpable resolve. “That has to be something that I hold on to.”

*****

To learn more about Bryan Stevenson’s work, visit the Equal Justice Initiative and watch True Justice: Bryan Stevenson’s Fight for Equality.