This excerpt originally appeared in the January/February issue of ESSENCE magazine, available on newsstands now.

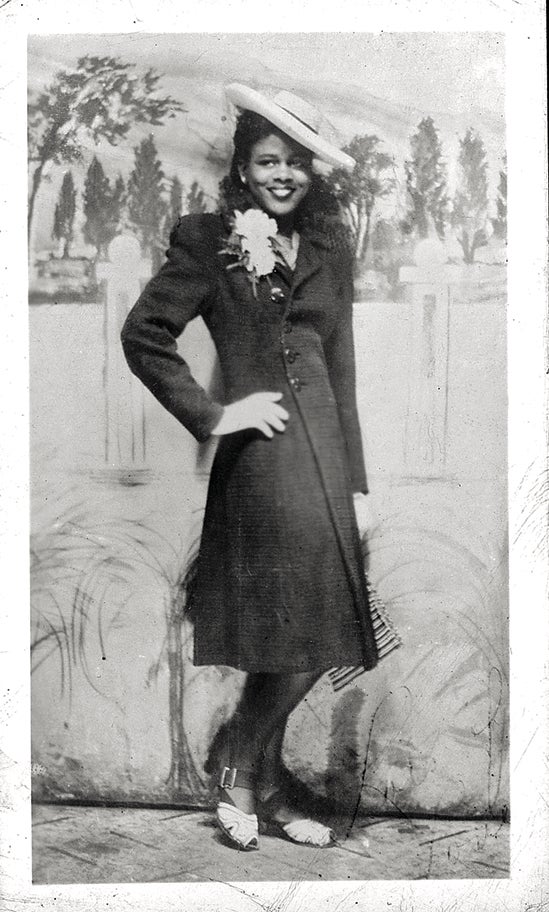

The era I grew up in both deepened my racial wound and soothed it with the healing balm of the arts. My childhood spanned the 1920s and 1930s, two of the most economically memorable and culturally rich decades in American history—a period when Negro literature, music and culture flourished. The Roaring ’20s rollicked joyously with jazz, decadence and illegal whiskey, while the thunderous market crash of 1929 rattled nerves throughout the ’30s. What these shifts meant to daily life, or whether they had any noticeable consequence at all, depended upon where you lived and how much you were able to earn, both of which were inextricably tied to the color of your skin.

The United States has never been “one nation under God” but several nations gazing up at him, dissimilar faces huddled beneath a single flag. In white America, the ’20s may have roared, but in my Black world—in what has been called the Other America—the decade also moaned. The fact that the Great Depression was given a name just meant that enough whites were now suffering alongside us to warrant an official title.

New York City earned its wings during the ’20s. The five boroughs overflowed with more than five million residents, moving the city ahead of London as the world’s most populous. By boat and by rail, by foot and by any means necessary, immigrant families flooded in, carrying with them the same dreams my own parents had clutched when they arrived from the Caribbean island of Nevis. During phase one of the Great Migration, millions of colored folks, as we were then called, moved from the rural South to New York City and other urban centers around the Northeast and Midwest. The Ku Klux Klan had raised its burning crosses with increasing height and frequency, signaling it was long past time for us to flee. Those who came to New York mostly settled in Harlem, then the largest Black community in the country. Uptown West was the place to be.

The nation began tapping its toes to bebop during the Jazz Age. If jazz was America’s first musical superstar, then Harlem was that star’s grand arena. Anyone eager to cut a step while relishing big-band brilliance stopped by the Savoy Ballroom (birthplace of the Lindy Hop and land of the Charleston and Fox Trot) or the Back Room (the speakeasy’s entrance was hidden behind a bookcase).

In white America, the 20s may have roared, but in my Black world… the decade also moaned.

Cicely Tyson

The Cotton Club, then on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue, was the ultimate hot spot. Night after night in that decade and beyond, greats such as Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, Cab Calloway, Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong, Fats Waller, Bessie Smith and Jelly Roll Morton delivered hankielifting performances, riveting audiences with their artistic genius. The music’s electrifying spirit could not be contained, even amid a strictly religious upbringing like my own. The city pulsated with revival, and as a child, I could feel the fervor.

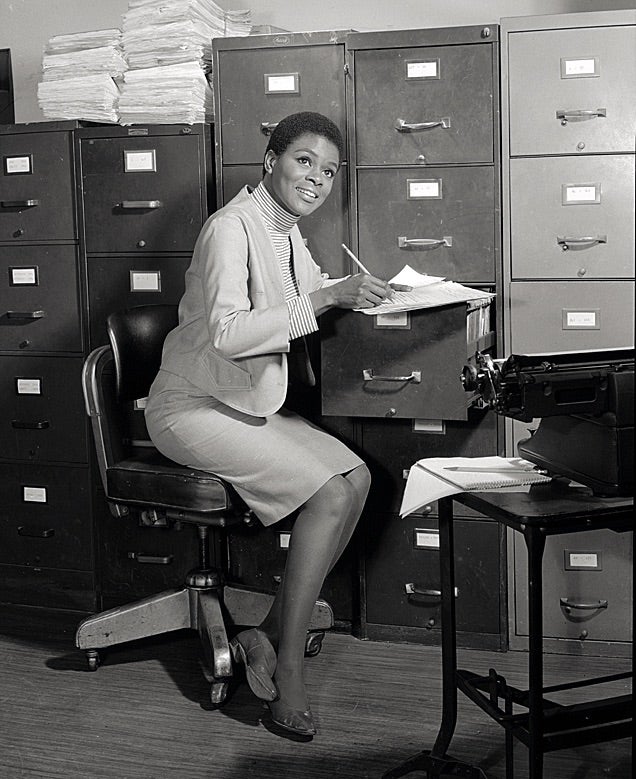

Jazz stirred at the center of a broader cultural movement, the Harlem Renaissance—a profound social, intellectual and artistic awakening in Black America that spilled over into all facets of society. Renowned philosopher Alain Locke, who penned the movement’s definitive text, The New Negro (1925), called the era “a spiritual emancipation.” James Weldon Johnson had his own description for it, “a flowering of Negro literature.” A historically shackled and voiceless community now demanded its full freedom and its say. It was our first opportunity in this country to define ourselves, to express our unique identity and declare our humanity.

The chorus of gifted literary voices that Locke gathered in The New Negro—which includes essays, poetry and fiction by writers such as Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Claude McKay—delivered the movement’s rallying cry for Black autonomy and self-respect. Locke, who earned his doctorate at Harvard University, was the first Black Rhodes Scholar and served as a philosophy professor at Howard University, encouraged artists to look to Africa for inspiration. The path to Black progress, he understood, began with self-determination and a regard for our homeland heritage. “The question is no longer what whites think of the Negro,” he wrote in his anthology, “but of what the Negro wants to do, and what price he is willing to pay to do it.”

Locke and his contemporary W. E. B. Du Bois, one of the most distinguished scholars of the 20th century and the author of The Souls of Black Folk (1903), held differing views about Black aesthetic expression and its role in the movement. And yet the two shared the conviction that the arts were essential to forging a new Black identity. With the Black elite at its helm, the Renaissance shined its light into every corner of the artistic community, from litera- ture and music to the performing and visual arts. Shuffle Along, which was produced, written and performed entirely by African Americans, debuted on Broadway in 1921, showcasing the talents of Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson and Adelaide Hall. Aaron Douglas, the eminent painter and graphic artist who produced the illustrations for The New Negro, created hundreds of images that evoked Black pride and captured the Renaissance spirit.

The Depression was just one of a series of devastations Black people endured during the ’30s. In 1931, long before the Exonerated Five were deprived of justice, the Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teenagers, were falsely accused in Alabama of raping two white women on a train. In a case of blatant racial bias, an all-white jury convicted the boys and sentenced eight of them to death. The following year, the U.S. government sanctioned the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a 40-yearlong health assault on our community. Biomedical research doctors recruited impoverished Black men with the promise of free medical care. Scores of our men were used as guinea pigs to study the long-term effects of syphilis, unaware that they were being denied treatment long after penicillin had been discovered as a cure.

The attack on our humanity continued in 1934. That year, the Federal Housing Administration established redlining, a set of racially discriminatory real estate and banklending practices that barred Blacks from purchasing homes in white neighborhoods—and thus set the stage for the wealth disparity between Black and white households that remains to this day. Home and land ownership are the primary means by which Americans have historically amassed wealth, and when Blacks were locked out of bank loans and segregated into slums, we were robbed of the potential to build fortunes. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal brought a measure of relief for poor Blacks, but some of its policies, such as redlining, made the New Deal a raw one for us.

It’s no wonder that many African Americans carry a lingering distrust of whites, even those we sincerely love and embrace. Given the horrors of our abuse in this nation, we are understandably wary. To ever heal these deep racial traumas—and seldom has it felt more urgent that we do—we must acknowledge that they indeed still exist, throbbing and tender beneath the surface, spilling over, like molten rage, into the streets. As difficult as it is to recall this country’s atrocities, it is essential that every American of every color does so. It is critical that we connect our ugly, centuries-long history with our times now, a cop’s knee on George Floyd’s neck and bullets riddling Breonna Taylor’s body. And even when the impulse arises to cringe and look away from a system predicated on Black oppression, a system that is still doing precisely what it was designed to do, we must stare into the face of our past and examine what happened here, on our soil—much of it less than a lifetime ago, a lot of it happening now. Turning a blind eye to our history has not saved us from its consequences.

My early years played out during these two wildly different decades—the first a cultural resurrection and the next a painful reckoning. In 1939, during the last days of the Depression, Billie Holiday stepped bravely up to a microphone at Café Society in New York’s Greenwich Village and sang, for the first time, her lyrical protest anthem, “Strange Fruit”:

Southern trees bear a strange fruit / Blood on the leaves and blood at the root / Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees.

A bitter crop, battered and dropping. The bruised and blood-stained carcass of the Other America.

From the book Just As I Am: A Memoir by Cicely Tyson with Michelle Burford. Copyright C 2021 by Cicely Tyson. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers