The average American 16-year-old spends her days planning for junior prom, deciding what colleges she will apply to and obsessing over issues like dating, pimples and grades. Not Cyntoia Brown. At 16 she was wearing an orange prison jumpsuit and facing a jail term while having a documentary filmed about her life. That was Cyntoia Brown’s existence in 2006. Instead of sitting through high school chemistry, she sat in a Tennessee courtroom waiting for a judge to pass down her sentence. Filmmaker Daniel Birman captured the trial in his 2011 documentary on the case, Me Facing Life: Cyntoia’s Story.

Brown was a teenager when this began. “We started the conversation,” Birman said in the documentary. “This is a young girl who’s at the tail end of three generations of violence against women.”

In 2006 the judge sentenced Brown to life with the possibility of parole after 51 years for the murder and robbery of a 43-year-old man, Johnny Michael Allen, on the evening of August 6, 2004. Though a teen at the time, Brown was tried as an adult and transferred to the state’s primary facility for female offenders in Nashville to serve out her sentence. Brown alleged that she had been forced into prostitution by her pimp, Garion L. McGlothen, also known as Kutthroat.

Brown stated that Allen offered to pay $150 to have sex with her, and that while she was at his house, she began to fear for her life and shot him with a gun she had in her bag. Prosecutors painted a different picture of what happened, insisting that Brown wasn’t a victim but someone who intended to kill and rob Allen. Authorities noted that the real estate agent was shot in the back of the head as though he was sleeping. Prosecutors also said that several of his firearms, as well as the pants with his wallet in them, were stolen.

We sat down with Brown in Nashville a little over a month after her release from prison to talk about the events of that night and her life since, making it her first interview. The now 31-year-old doesn’t deny shooting Allen, but in one of the few interviews she has given since becoming a free woman, she maintains that it was in self-defense. She says that while she was with Allen, she felt intimidated and trapped, and she believed in that moment that she saw him reach for something. She assumed it was a gun.

“The whole time I’m lying on this pillow, trying to pretend like I’m asleep, but really I’m looking at him, and I’m like, I’ve got to get out of here. Crap. What’s he going to do?” Brown remembers. “I’m thinking back to everything with Kut—always on edge, always waiting.” Her association with Kutthroat had taught Brown to be prepared for the worst.

In The Beginning

Her life hadn’t always been so dire, though her beginnings were rough. She was born to a Black father and a White alcoholic mother who became hooked on crack and gave her daughter up for adoption. A Black couple, Ellenette Brown and her husband, took her in and raised her in what she refers to as a loving home in her newly released memoir, Free Cyntoia: My Search for Redemption in the American Prison System. But even though she had landed in a supportive family, it wasn’t enough for Brown.

“I think I pushed my mother away because she was trying so hard,” Brown says of her relationship with the woman who raised her. “As a teen I wanted to do what I wanted to do. I didn’t want structure. My mother was all about structure.” When Brown got into trouble, she would be forced into counseling. “Sometimes in life you kind of just want to be there doing what you want to do,” she says of her tumultuous teen years. “You want to dwell in that brokenness. And that’s where I was at that point. No matter how hard my mother tried, I just wasn’t receptive to changing. You have to want it.”

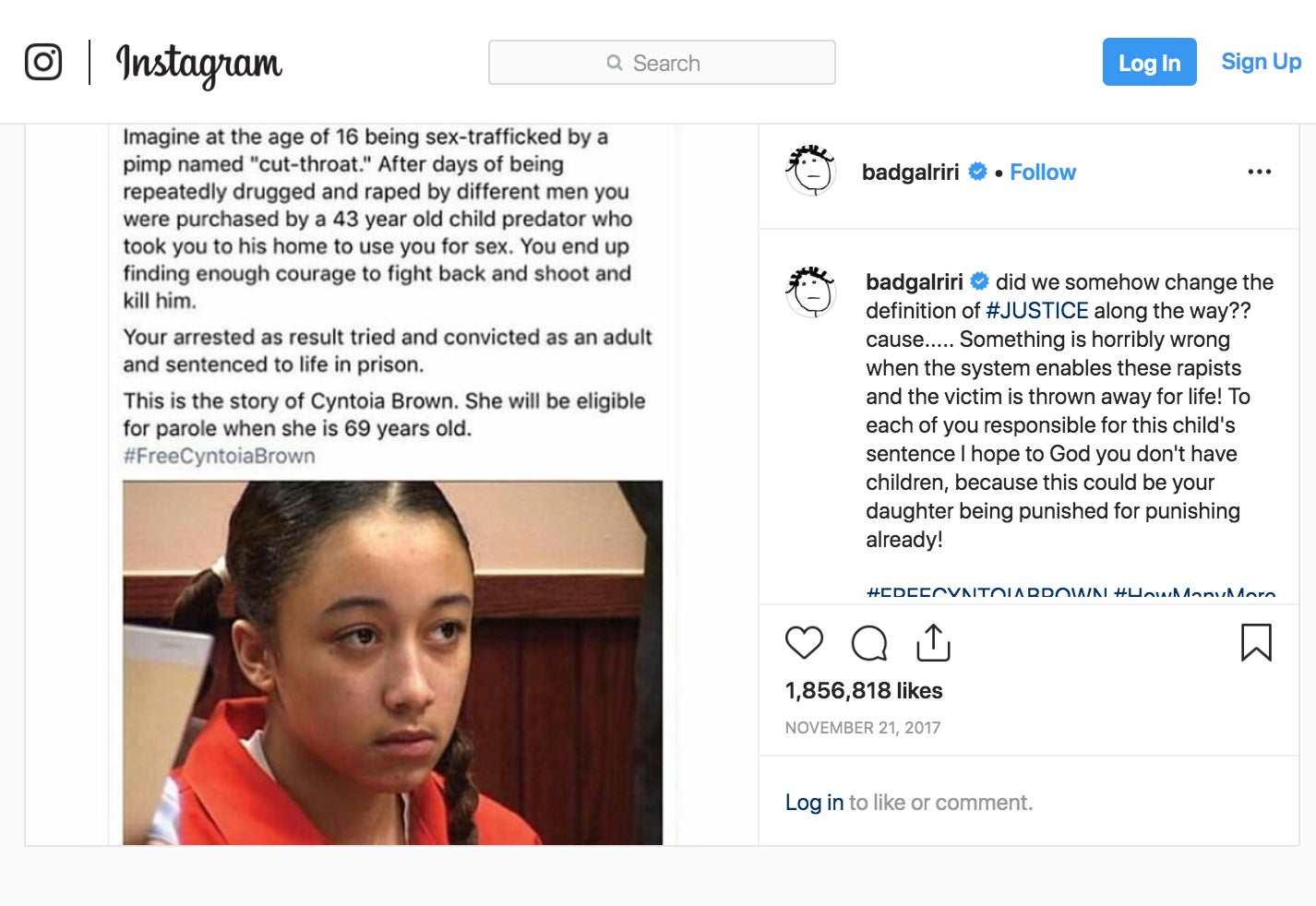

During her time in prison, Brown began to want it. She tried to appeal her murder conviction and have a chance at rehabilitation. And thanks to a tweet from Rihanna on November 21, 2017, millions more people began wanting it for her. More than ten years after Brown’s verdict and sentencing, her case was drawing national attention with the help of celebrities and the power of social media.

#FreeCyntoiaBrown became a trending hashtag that led people to question how a state could try a child as an adult. Prosecutors argued that Brown’s previous stints in the juvenile justice system and her drug use made the decision fitting. They wanted the world to know that the girl who wore pigtails at her sentencing wasn’t as innocent as she appeared.

Years later it’s obvious that the prosecutors’ perception of who Brown was during that trial still bothers her. She shares that neither she nor her court-appointed attorney thought she would be tried as an adult. “In the juvenile system, the goal is to remove the taint of criminality,” she says. “The goal is to rehabilitate you, to get you where you should be. At that point, I was like, there were some decisions that I made, some actions that needed to be addressed. There were some things that needed to be changed, and I was willing to take those necessary steps. When they said instead, ‘No, you’re going to the adult system, where rehabilitation is not the goal,’ then it’s like they feel like I can’t be fixed. They’re not even going to try to fix me.”

Promises Of A New Beginning

The idea of being tossed away is something Brown mentions in her book repeatedly. From being abandoned by her biological mother, with whom she has no contact, to being ostracized by her peers as a kid because she is biracial, to being placed at the Tennessee Prison for Women despite her being a child. Throughout her life, Brown has experienced her fair share of disappointment in relationships. But today she focuses on the people who showed up for her when her future looked most bleak, the ones who stood by her in 2017 and amplified her story to the public.

Following Brown’s viral moment with Rihanna, there were numerous calls for the state of Tennessee to grant her clemency. “What meant the most to me was just seeing how many people from all different walks of life supported me,” says Brown, who, despite her fear that she wouldn’t be rehabilitated in prison, managed to earn a bachelor’s degree there, and dreamed of creating a nonprofit. “All the letters that came, all the people who were praying for me, there were so many people.”

Still, after several unsuccessful attempts to appeal her sentence, Brown says that even with the renewed interest in her case, she didn’t allow herself to believe she might be released. But on January 7, 2019, her hopes were realized when then-Tennessee governor Bill Haslam commuted her life sentence and granted her clemency. This meant an early release for Brown with ten years parole.

On August 7, 2019, as Brown finally walked out of the gates of her Nashville prison, she was a married woman. In her memoir, she recalls receiving a letter from a man who caught her attention. “Cyntoia, My name is Jaime Long, but most people call me J. Long,” the note read. “It’s 5:52 in the morning. I couldn’t sleep and somehow I came across your story.” That communication was the beginning of a friendship between Brown and Long based on a shared belief in God and Christianity. The letters were followed by visits from Long, a former R&B singer with the group Pretty Ricky.

“He came along at a point when all my appeals had been denied, and I didn’t have hope,” Brown recalls. “We prayed through it, and because of him I started working on my relationship with God. And that’s when my federal appeal opened back up, which is unheard of.” Around the same time, their very public relationship garnered some scrutiny. Gossip websites wrote about Long being trouble, and people from his past chimed in to agree. Long was first introduced to Brown via -Birman’s film. “After seeing the documentary, the Lord put it on my heart to write her,” Long says. “It’s a real marriage.”

Free At Last

Now, having returned to the outside world after spending half of her life in prison, Brown is still finding her way. Everyday things like using technology can take some getting used to. As she adjusts, Brown is making sure to keep her circle of friends tight. “I’m in a completely different area socially,” she says. “I don’t associate with the same people, which I think is very important when it comes to growing from your mistakes. You have to make different decisions. You can’t just put yourself back in the same situations. I would never even associate with men like the ones I used to associate with. It’s just—it’s stupid. It would actually meet the definition of insanity.”

Instead of falling back in with her old crowd, Brown wants to use her newfound freedom for good. She’s currently forming a nonprofit organization, the Foundation for Justice, Freedom and Mercy, which will aim to shed light on the workings of the criminal justice system as she puts the college education she pursued while in prison to use. She’s even considering law school as an option. “I’m committed to the same fight that got me free,” she says. “I definitely think that there’s a need for reform, not just in prison but in sentencing and the way justice is [handed] out in our country. I’m committed to [fighting] for all the other people who are just like me.”

Makeup: Nikki Campbell/Bluartistry