August marks a century since the ratification and official adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment. This landmark law proclaimed that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” Surely, this legislation should have granted every American woman the right to vote.

However, this amendment did not fully protect the voting rights of all women; it primarily guaranteed the rights of White women. In its oversights, the Nineteenth Amendment echoed the sentiments of the women’s suffrage movement as a whole. Though both the amendment and the movement appeared to encompass the entire spectrum of women, in fact Black women were often relegated to the back of protest marches, with suffrage leaders failing to consider, much less understand, how Black women exist at the intersection of race and gender—and are marginalized by both.

Thousands of Black women had organized, marched, lobbied and participated in the struggle for voting rights, yet their interests and issues did not make it onto the agenda for most White suffragettes. Black women actively endured the trials and tribulations of the suffrage movements, but they were—and still are—largely shut out of both the victories and the commemorations.

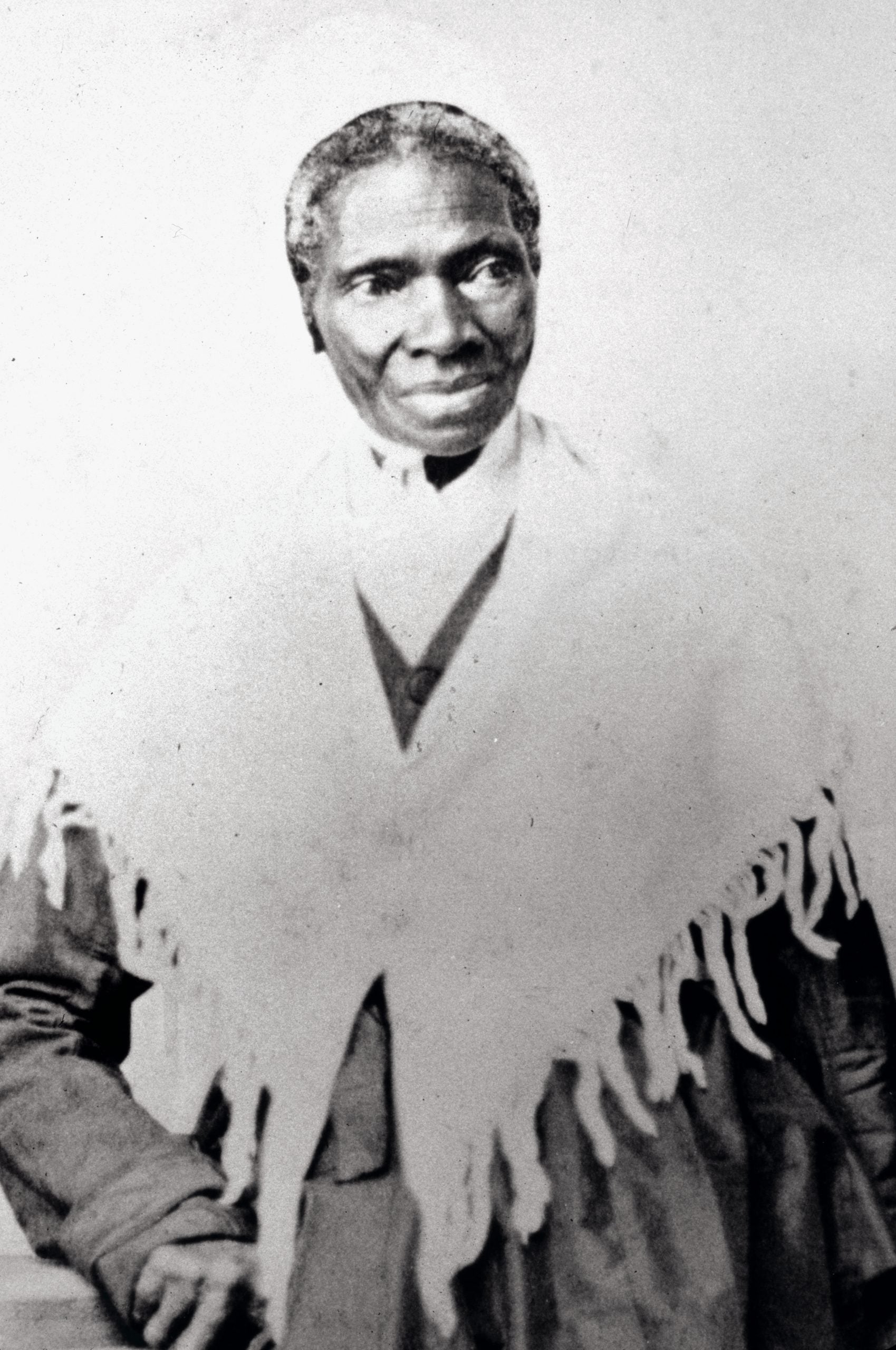

I have borne 13 children, and have seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

—SOJOURNER TRUTH

In 1851, at the Women’s Rights Convention, abolitionist Sojourner Truth delivered her renowned “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, poignantly illuminating Black women’s exclusion from the institution of womanhood: “I have borne 13 children, and seen most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman?”

Like many Black suffragettes, Sojourner championed the idea that race and gender were inextricable. The term “intersectionality” would not be coined until more than a century later, yet Black suffragists understood Black women’s dual social caste. As civil rights activist and suffragette Mary Church Terrell remarked, “a White woman has only one handicap to overcome—that of sex. I have two—both sex and race. I belong to the only group in the country which has two such huge obstacles to surmount. Colored men have only one—that of race.”

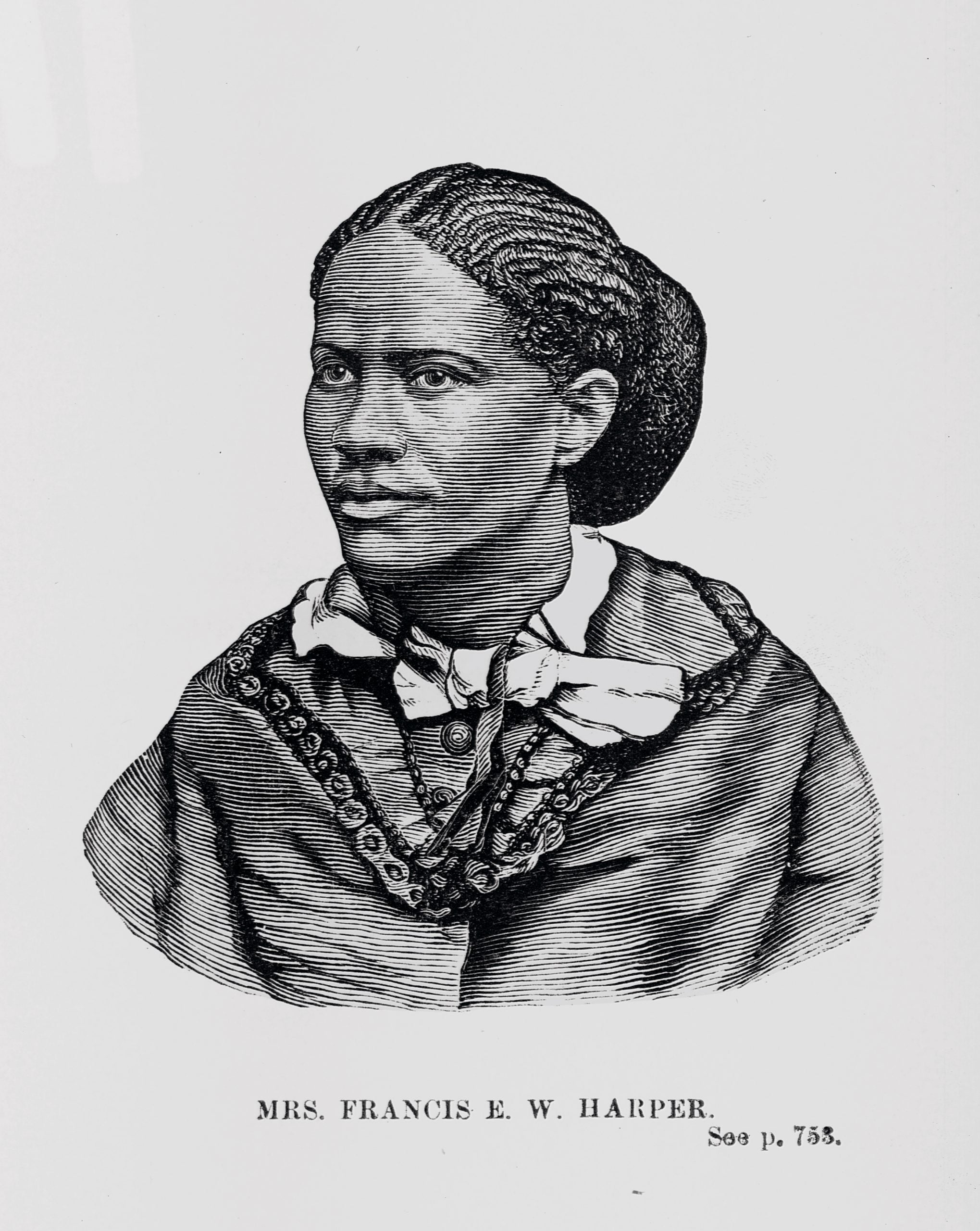

Within the suffrage movement, there was hardly a place for Black women. That is, of course, until Black suffragettes forged one. In 1896, Terrell, along with fellow activists like Harriet Tubman, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). A fusion of several local Black women’s clubs, the NACW took on the varied interests of Black women, from anti-segregation to suffrage.

A White woman only has one handicap to overcome—that of sex. I have two—both sex and race. Colored men only have one—that of race.”

—MARY CHURCH TERRELL

The words of the organization’s motto, “Lifting as we climb,” were Terrell’s own. One of the founders, Wells, later established the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago. In 1913, when a suffrage parade was organized in Washington, D.C., Wells and her group were invited to attend. There was one striking condition, however: Wells and the Black women of the Alpha Suffrage Club would have to march at the end of the parade, upholding segregation.

Wells renounced this condition, and instead her group cleverly joined the Illinois delegation in the middle of the parade. During her life, Wells crusaded against the atrocities of lynching and mobilized thousands of Black women to register to vote, canvass and educate others on the critical importance of going to the polls.

The Nineteenth Amendment’s official ratification in 1920, paired with the adoption in 1870 of the Fifteenth Amendment—which states that the right of citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude”—should have provided universal voting for all Black people. Instead, state laws still methodically disenfranchised Blacks seeking to cast a ballot by requiring literacy tests, character assessments, and the payment of poll taxes. Beyond these obstacles, Black people who attempted to go to the polls were often met with threats and violence.

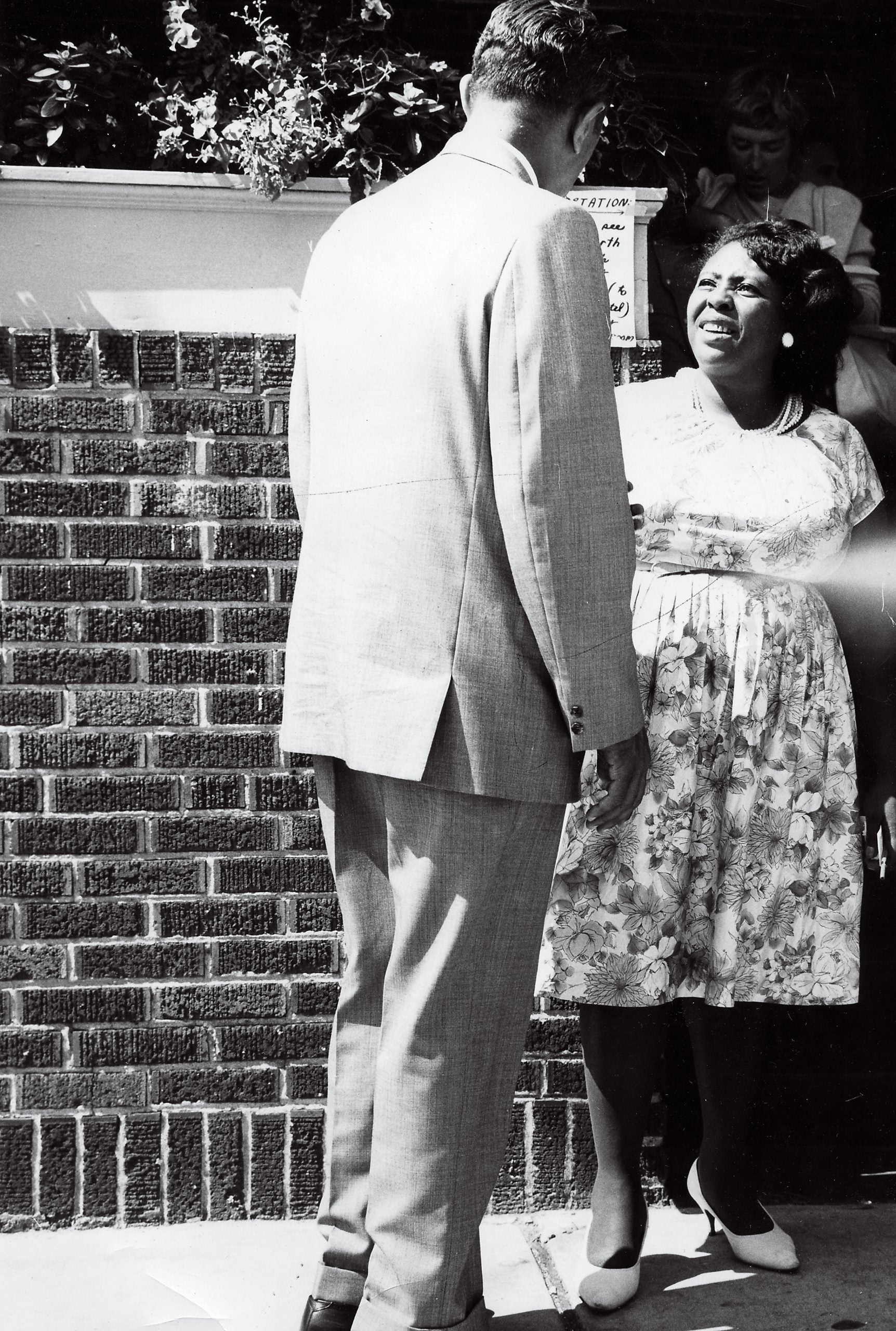

In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement transformed the fight for suffrage by registering voters, dismantling discriminatory laws, and resisting the violence and threats that Black families encountered when they attempted to exercise their rights. In 1964, Fannie Lou Hamer told the Democratic National Convention (DNC) that she was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.” Hamer had been a frequent target of antagonism, intimidation and violence as she registered Black families to vote through the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and advocated for equal voting rights for Black people.

By the time she made it to the DNC in 1964, after helping to found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) during Freedom Summer, Hamer had a specific demand—that the convention’s Credentials Committee award the MFDP seats as Mississippi delegates. Her insistence on representation mirrored communities of Black people across the nation who desperately wanted to see themselves in the bodies that governed them. Hamer, Shirley Chisholm and numerous other Black women carried the banner for those communities, mobilizing Black candidates to run for political offices.

In 1965, the Voting Rights Act was passed to bar racial discrimination in voting. Black women suffragists, advocates, organizers and activists took the lead in forging creative and impactful campaigns that led to the passing of this legislation. They understood, however, that just as the struggle at the ballot box had not ended with the Nineteenth Amendment, it would not magically cease 45 years later when Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

The spirit of suffragists and abolitionists lives on today as we continue to confront the disenfranchisement of voters in our communities. Now, as then, Black women are leading the charge, with Stacey Abrams way out in front as one of our most dynamic. As the first woman to lead any party in the Georgia Assembly and the first Black person to serve as a leader in the state’s House of Representatives, Abrams is no stranger to blazing trails. To say she is fed up by voter disenfranchisement would be an understatement.

On the heels of her 2018 Georgia gubernatorial campaign, which featured egregious acts of voter suppression, Abrams launched Fair Fight, to ensure voter protections in battleground states. She also started several other organizations dedicated to voter education, registration and protection—including Fair Count and New Georgia Project. Black women have been and remain integral to the success of American liberation movements.

In light of this summer’s uprisings in response to police brutality, ongoing systemic racism and social institutions entrenched in White supremacy, now is the perfect time to make a stand. In this moment, everything is possible, even a Black woman vice president. But we must be willing to seize everything that has historically been kept from us—including the right to exercise our power at the polls