On May 13, 1985, the Philadelphia Police Department bombed a West Philadelphia row home occupied by MOVE, a Black liberation organization—a family—committed to exposing the white supremacist corruption at the core of the city’s leadership. MOVE had become known for calling out Frank Rizzo, who served first as the city’s police commissioner, then mayor, and the injustice system that flowed from his administration. And on the day of the bombing, a stunned city sat glued to television screens and watched as 6221 Osage Avenue became engulfed in flames, and nearby residents ran for their lives.

The Philadelphia Police Department killed 11 people that day, including five children, ages 6 to 13: Tree Africa, Netta Africa, Phil Africa, Delisha Africa, and Tomaso Africa. The adults murdered were Raymond Foster Africa, Conrad Hampton Africa, Frank James Africa, Rhonda Harris Ward Africa, Theresa Brooks Africa, and MOVE founder John Africa. Sixty-one homes were destroyed in the Cobbs Creek neighborhood. More than 250 people were left unhoused.

There were only two survivors: Ramona Africa, then 29—who is currently battling cancer that she believes was caused by chemicals in the four pounds of C-4 military explosives that the police used to bomb the MOVE house—and the then 13-year-old Birdie Africa, who began using his birth name Michael Ward after the bombing, who died by accidental drowning in 2014 at the age of 41.

This was not the Philadelphia Police Department’s first time brutalizing MOVE. On August 8, 1978—seven years prior to the bombing that, despite its shocking cruelty, has flown largely under the nation’s radar, and two years after Janine Africa’s three weeks old newborn Life was knocked from her arms during a scuffle with police, his skull fatally crushed—nine MOVE members were incarcerated following a police raid of their home in Powelton Village. Police showed up allegedly to remove them because they had been squatting.

“…cops filled our home with enough tear gas to kill us and our babies, while SWAT teams covered every possible exit…we had 10 thousand pounds of water pressure per minute directed at us from 4 fire department water cannons…As the basement filled with nearly six feet of water we had to hold our babies and animals above the rising water so they wouldn’t drown.” —MOVE 9

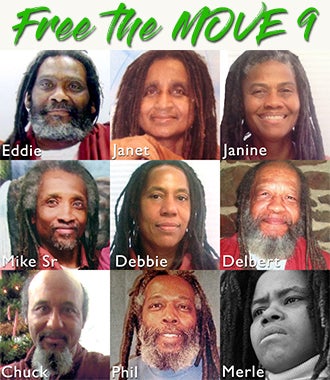

During the orchestrated, militarized attack on the MOVE family, police officer James Ramp was struck by a single, fatal bullet. Subsequently, Chuck Africa, Debbie Africa, Delbert Africa, Eddie Africa, Janet Africa, Janine Africa, Merle Africa, Mike Africa Sr., and Phil Africa were convicted of third-degree murder in Ramp’s death and sentenced to up to 100 years in prison. Janine’s son Phil was killed in the MOVE house when it was burned to the ground, as was Delbert’s daughter Delisha.

At the core, MOVE’s story is about struggling to be free in a nation accustomed to Black subjugation and being met with the full, violent force of the state. It took almost four decades to free them all—or, rather, the ones who remained. Phil and Merle would die in prison before the efforts of the movement to free them bore fruit.

As noted by an exhaustive, two-year investigation by the Guardian, Debbie was the first to be released in June 2018. Then came Mike Sr. in October 2018. Janine and Janet were set free in May 2019; Eddie followed one month later; Delbert was released in January 2020; and Chuck, the youngest of the group when he went in at just 18-years old, was finally released in February.

Passing The Baton

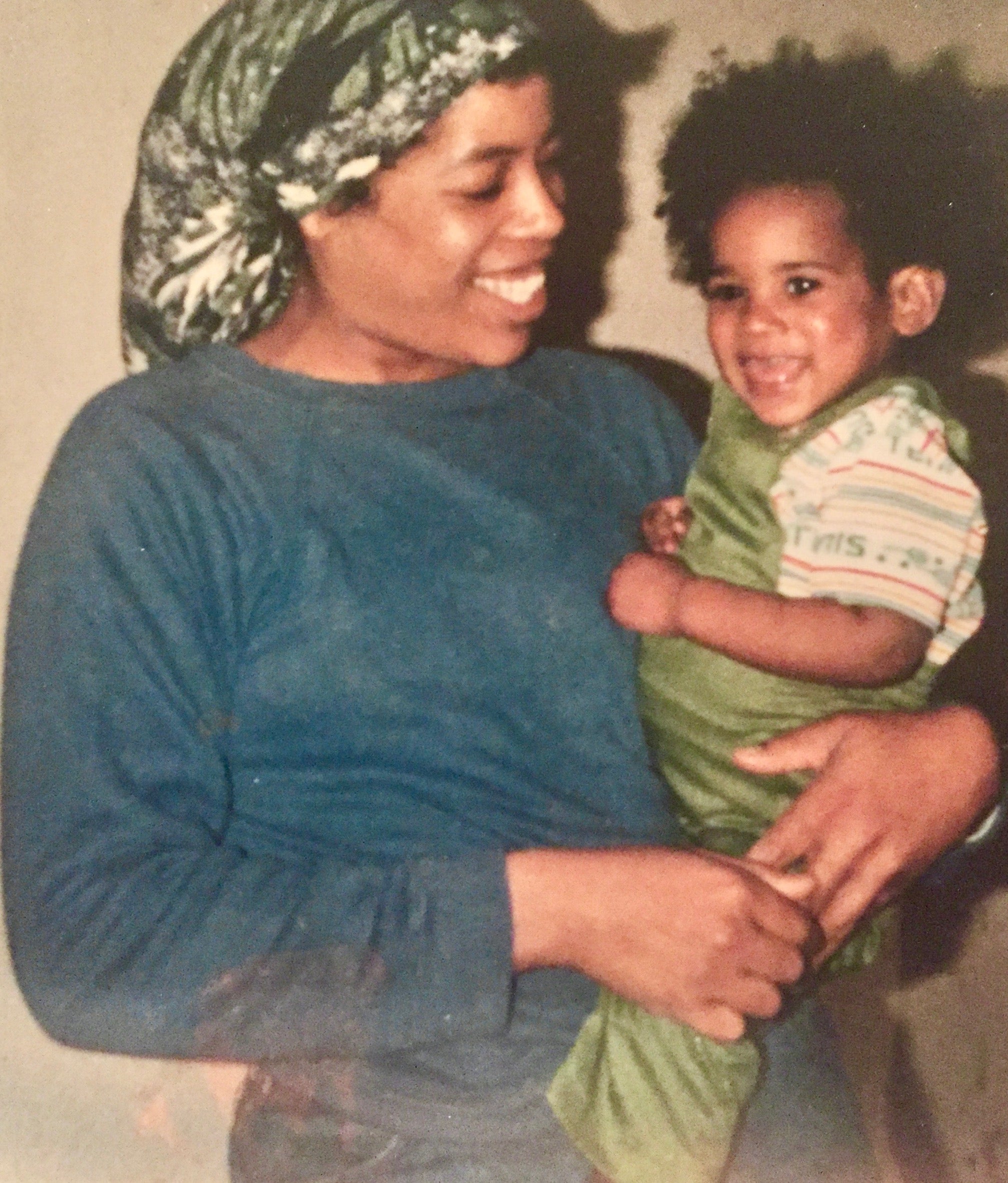

Mike Africa Jr., son of Debbie and Mike Sr., and Chuck’s nephew, was born five weeks after his mother was incarcerated. She gave birth to him and kept him hidden for the first few days of his life. When he was discovered, guards took him and his mother to the hospital, where his grandmother came and got him. She would raise him with the help of the rest of the Africa family.

And the whole time, he was thinking about freedom.

“I started working on freeing my family when I was 13-years-old, and now I’m 41,” Mike Jr. tells ESSENCE. “I met with investigators. I met with local and state politicians. I met with street activists and we marched for countless miles and protested countless times.”

“And, still, getting them free was not an easy thing,” he continued. “The time that it takes for Black people to get released, even if they’re innocent, is much longer than other people. And, sometimes, it didn’t seem like it would happen.”

Africa said that he doesn’t believe in giving up, and because of that, their hard work was successful.

“We kept it going,” he said with determination still in his voice. “And, fortunately, we got MOVE 9 out of there.”

Rhonda Africa, one of the MOVE members killed in the May 13, 1985, bombing, became like a surrogate mother to young Mike. “She didn’t make it out,” he said quietly.

While media reports often called MOVE members aggressive and violent, Africa says that’s nothing but the oppressor talking, and that it’s a form of deception and suppression.

“The media and politicians will tell us to be non-violent,” he says. “‘If you’re going to protest, do it peacefully,’ they say. It’s a real tragedy that people take guidance from their oppressors. You don’t see police officers being non-violent. You don’t see them being peaceful. You don’t see them being kind or gentle. They certainly weren’t to my family.”

“Even today, there are police officers who go out strangling people to death, it’s caught on video,” says Africa referring to the death of Eric Garner in 2014. Former NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo killed Garner when he placed him in a banned chokehold. Meanwhile, Ramsey Orta, the man who filmed the fatal incident, was targeted by police officers, harassed, and ultimately arrested.

“People need to be really clear about who the oppressors are,” Africa said.

Free Them All

There are still revolutionaries behind bars for the crime of seeking liberation for Black, Brown, and Indigenous people in this country. From Leonard Peltier and Sundiata Acoli, to Mumia Abu-Jamal, and other Black Panther and Black Liberation Army members, to Joshua Williams—the protester sentenced to eight years in prison for starting a fire in an outside trash can during the Ferguson Uprising after the extrajudicial slaying of Michael Brown Jr.—it is imperative that political prisoners feel supported, respected, and remembered. And that their fight, their bravery, and their sacrifices not be in vain.

“I talked to my Uncle Chuck the other day,” Africa says. “He said, ‘Mike, there were times when I didn’t think that I was going to make it out of there. I would look at the guards, and how they would treat me, and over the years, I started to think there were no more good people left in the world. But coming home to my family and all of the support…I remembered that there’s a lot of good people in the world. I know now that dreams do come true.'”

Africa paused, the weight of his uncle’s words lingering. He says there’s a feeling of release now that his Uncle Chuck was able to walk out of prison and not be carried out. There’s also a bone deep feeling of relief now that his parents are home, because they could have died in prison. That matters.

“Even though they’re older and have their ailments, they get to enjoy life for awhile longer,” Africa says. “I was in prison with them all. I was in my mom’s stomach, but I was in there with them, you know?”

“And, after all these years…I don’t even think I realized that when they finally came home, for the first time, I felt like I was free, too.”

Free them all.

****

Click here to learn more about how you can support MOVE, most urgently right now, Chuck Africa and Ramona Africa.

Click here to support Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Click here to support Josh Williams.