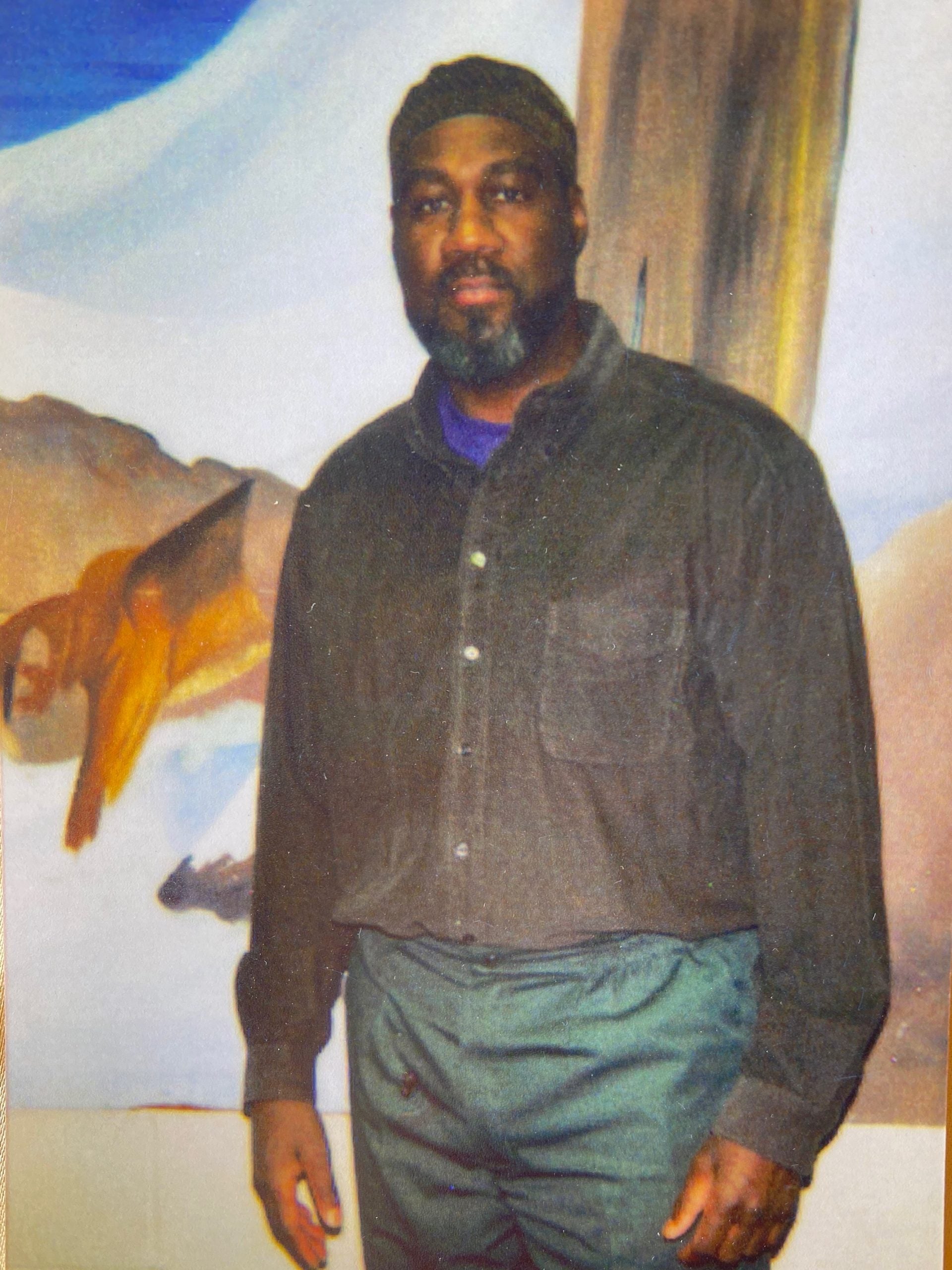

When I meet him at a program held in one of New York State’s maximum security prisons coordinated for students from my City University class, he is already 18 years into a 25 to life sentence. A former Black Panther and human rights activist, he was convicted, along with two others for the 1971 killing of two police officers. He will express remorse for their deaths. He believes in life, peace. He recommends some books for me to read and it is in this way and with this man that I begin to learn about the Black Panther Party and COINTELPRO, the secret FBI program coordinated by their head, J. Edgar Hoover, which was designed to disrupt any organized effort to create a society rooted in human rights and justice. Hoover, who had designated the Black Panthers as the single greatest threat to the United States, went to war against them with a wanton intensity.

When he joins the Party at 16, of course, Jalil Muntaqim does not know this.

He knows only the unrelenting poverty, the stack up of Black deaths by law enforcement and white supremacists. He knows things have to change. And in the quick and brutal way that people of my daughter’s generation will learn that the killing of Michael Brown, the brutality against, then shocking death of Sandra Bland in police custody, are less exceptions than they are rules, so, too, will I learn that the killings of Eleanor Bumpers and Michael Stewart, horrors that pockmarked moments in my own 80s childhood, were the rule—and had always been. I begin writing Jalil and eventually, visiting him. I tell him what I’ve been learning, to which he says quietly one afternoon, “They been killing us a long time.”

That was 31 years ago.

Jalil Muntaqim was one of the youngest members of the Black Panther Party. He was not yet 19-years-old when he, along with Albert Nuh Washington and Herman Bell, were charged with the May 21, 1971 killings of two New York City police officers, Waverly Jones and Joseph Piagentini. In 2000, Nuh passed away in prison at the age of 64 and Herman Bell was granted parole in 2018. Since then, he has lived a quiet and peaceful life.

But Jalil, despite an exemplary record, a reputation as a peacemaker and teacher, a profound showing of remorse, the support of the New York State Black and Puerto Rican Legislative Caucus—and despite even the support of Waverly Jones’s son, who would say that, “There was rampant racism both individual and institutional. Many took to the streets. Some engaged in militant actions, including violent ones. There were also many instances of police violence,” Jalil was denied parole for the 11th time in January of this year, 18 years past when he was first eligible for it.

They been killing us a long time. — Jalil Muntaqim

Two months later, the pandemic hit and New York’s prisons and jails became an epicenter within the epicenter. Sullivan Correctional Facility where Jalil is being held this 50th year of his incarceration, reported that people had been diagnosed with COVID-19. We—his family, friends and attorneys—were worried. An elder now at 68-years-old, a stroke survivor and a man living with hypertension, he was at risk. We knew that if he wasn’t released, a 25-year sentence could become a death sentence—which is what on April 27th the judge presiding over a hastily called habeas corpus hearing would say. He ordered Jalil, who was COVID-19 negative, released, so that he did not contract or spread the illness. We were thrilled but measured. In the tradition of his late father, the former governor, Mario Cuomo, who oversaw the largest prison expansion New York had ever seen, Andrew Cuomo has stood firmly against reforms to criminal justice others of both parties have now embraced.

New York is not the progressive bastion it pretends to be.

“We’ll celebrate when he’s out,” someone said in the moments after the Court’s decision. Even still, I held onto hope because the judge, unlike secretive and politically manipulated parole boards, was following both the spirit of parole and the best public health and safety recommendations. And actually, he was honoring the words—disingenuous as they were—of Gov. Cuomo, who declared that the state didn’t and wouldn’t lose anyone who could have been saved. I knew that was a lie when he said it but if someone had told me that the harshest blow would come from a woman who defined herself as community responsive and committed to police and other reforms critical to African Americans, I would have thought that person was being horribly jaded.

Letitia James, New York’s Attorney General, was a Brooklyn girl, a woman from a working class background. She was accessible. We felt we knew her. At 61 years old, she was also a woman whose election was made possible in part by the very work Jalil committed his life to all those years ago, as a boy of 16. But it would be James who would appeal the decision in this grandfather’s case.

When I tell one of my friends, an attorney and a man who served as a teacher, assistant principal and principal in New York City, that James has appealed Jalil’s release, he says with disgust, “What do we even work to elect Black, progressive leaders for if they’re only going avert the law and genuflect before a bunch of racist politicians who never cared about us?”

On Monday May 25th, four weeks to the day that a judge ordered him released in order to ensure his health–and likely avert an Eighth Amendment challenge, Jalil was hospitalized for COVID-19. If we lose him, the blame can be placed at the feet of a Black woman we elected because she said she honored the ideals fought for during the Civil Rights and Black Power eras.

asha bandele is an award-winning journalist and New York Times best-selling author. She has been writing for ESSENCE for more than 20 years.