Jane Bolin became the first Black woman to break down many barriers during her life. However, the title for which she holds the most recognition is that of the first Black woman judge in the country.

Using her position from the bench as a family court judge, Bolin fought against racial discrimination within the system and was a fierce advocate for children, particularly children of color, whose cases she oversaw.

Bolin’s story of legal service and general activism begins at home. Born on April 11, 1908, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., her father, Gaius C. Bolin was the first Black graduate of Williams College and had his own legal practice. Bolin was also the founding member of the local NAACP and later in life became the first Black president of the Dutchess County Barr Association.

According to the New York Times, Bolin fell in love with her father’s leather-bound law books and decided to do her part as she became more and more aware of the articles and pictures of lynchings that the NAACP’s official publication, Crisis magazine published.

“It is easy to imagine how a young, protected child who sees portrayals of brutality is forever scarred and becomes determined to contribute in her own small way to social justice,” she recalled in a letter around the time of her retirement in 1978.

Bolin would go on to continue her studies at Wellesley College, the prestigious, private women’s liberal arts college in Massachusetts. She was one of two Black freshmen attending the school…where racism was so rampant (and they so ostracized) that the two of them opted to move off-campus. Despite the trials that Bolin faced, she graduated in 1928 as one of the top students and was named a “Wellesley Scholar.”

Even though Wellesley acknowledged her brilliance as a student, when she spoke to a guidance counselor at the school about a possible law career, she was told that “there was little opportunity for women in law and absolutely none for a ‘colored one’”. Even her own father discouraged the notion at first according to the Times, although he emphasized that lawyers had to grapple with “the most unpleasant and sometimes grossest kind of human behavior.”

However, once he saw that his daughter’s mind was made up, the older Bolin would throw his financial and moral support behind her to help her accomplish her goals.

Jane Bolin would be accepted into Yale Law School, where she would ultimately become the first Black woman to earn her law degree from the esteemed institution. She would later become the first Black woman to join the New York City Bar Association.

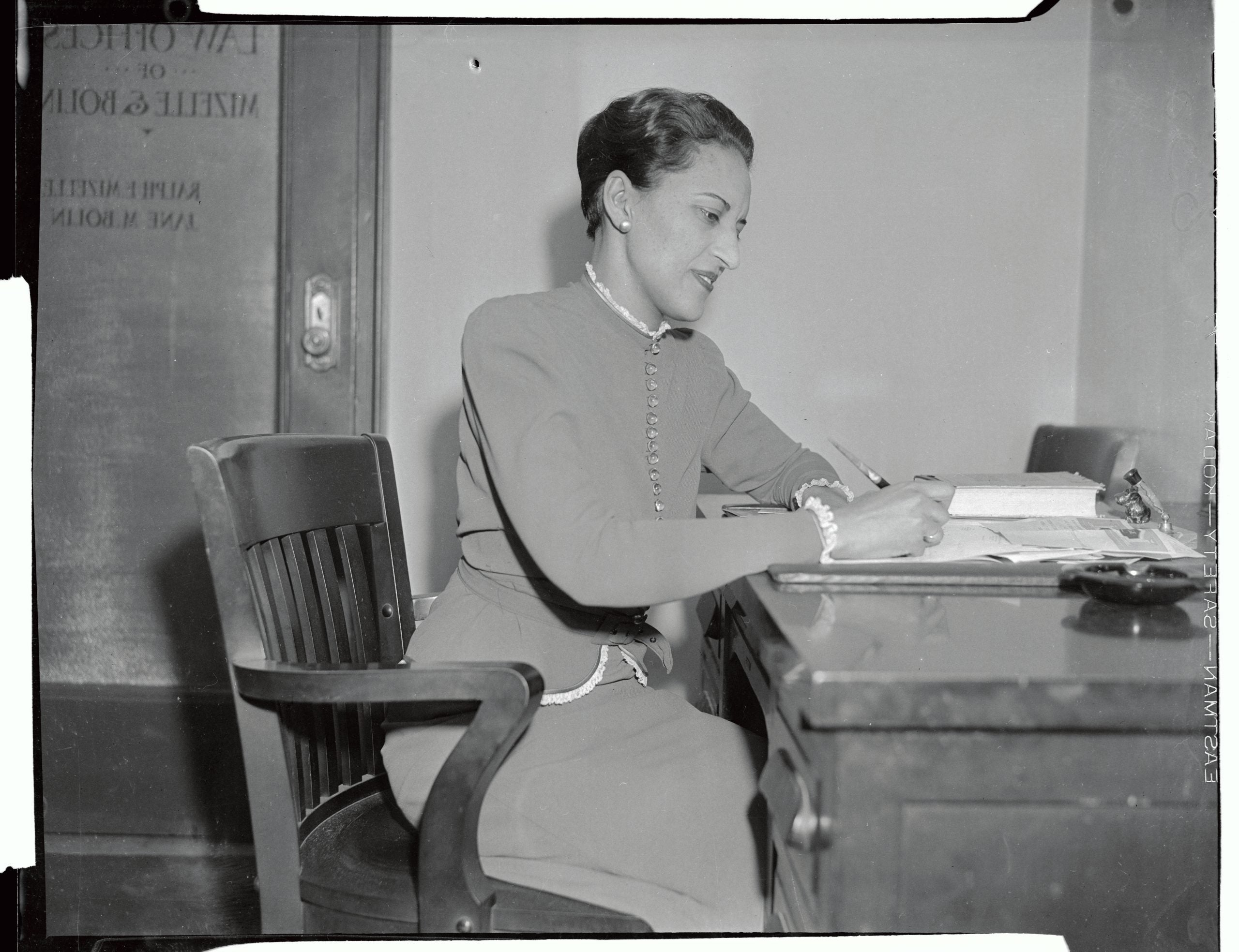

After her graduation, Bolin apprenticed in her father’s law office. Dismissed by local law firms due to her gender (and likely also her race) she later went on to practice law with her first husband, Ralph E. Mizelle, who later died in 1943.

Not giving up on her goal, in 1937, Bolin would be appointed Assistant Corporation Counsel of the City of New York, also breaking the ceiling as the first Black woman attorney hired by that office.

Two years later, in a ceremony at the World’s Fair which had just opened, she would be appointed (and sworn in) as a judge of the Domestic Relations Court (now called Family Court) by then-New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, sealing her title as the first Black judge.

As a judge, Bolin led the charge (and change) of breaking down racial barriers and segregation within the system she was a part of. She led the charge of requiring child care agencies that got public funding to accept children regardless of their race or ethnicity. She also ended the practice of assigning probation officers, based on race or religion.

Despite breaking down barriers and crashing through ceilings, Bolin remained focused on her work, dismissing the “fuss” that people usually make about her trailblazing ways.

“Everyone else makes a fuss about it, but I didn’t think about it, and I still don’t,” she told the New York Times in a 1993 interview. “I wasn’t concerned about first, second or last. My work was my primary concern.”

Bolin would be reappointed to her seat by three more mayors, for three more ten-year terms. She only stepped down from the bench when she reached the mandatory retirement age of 70 in 1978, and wasn’t too happy about it, either, quipping, “They’re kicking me out.”

Still, even after retiring at the age of 70, Bolin continued to advocate for children’s rights and education. She volunteered as a tutor at New York City public schools for about two years post-retirement and ultimately went on to serve on the New York State Board of Regents.

When she died on Jan. 8, 2007 at the age of 98, she left behind a legacy of a fierce advocate, who despite remaining focused on the work, carved out a decisive path for the representation in the legal system today including the unprecedented number of Black women who were sworn in as judges in Harris County, Texas last year.