On the heels of the Los Angeles riots in 1992, no one cared about Black people and our struggles. And it didn’t matter which side of the coin you were on—the media would paint you as a threat or even a danger to society. Amid that chaos, Black women might as well have been nonexistent. As a result, Black female leads in film and television were exceptionally rare in the early 90s. Representation and diversity and inclusion had not become a trend just yet. And then came John Singleton.

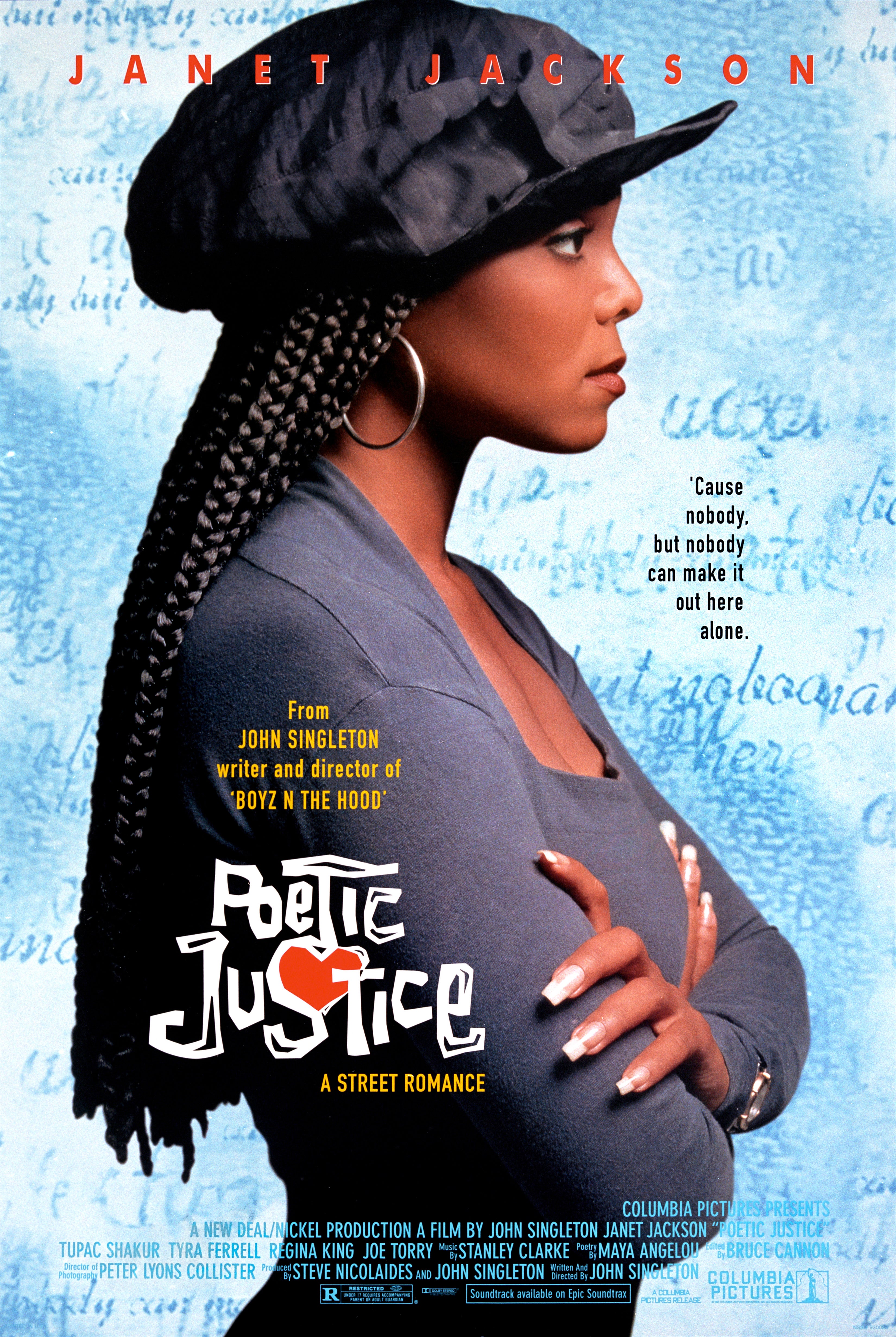

The freshly-minted industry disruptor followed up his explosive debut of Boys N The Hood with Poetic Justice, a love story, featuring not only two of the biggest artists of the decade, but also centering a young Black woman. Poetic Justice was the first time I’d prominently seen a Black woman onscreen, openly dealing with grief and depression after tragically losing a loved one to violence. And he did it with a care and compassion that would go on to impact his work. Even in the complexity of his subject matter—violence, racism, and poverty—Singleton made space for the resilience of Black women.

Part of the magic of him as a director laid in his unapologetic approach to telling our stories.

“When I think of him, I think of him being an innovator. He came along at a time where people of color didn’t have the opportunities they have now in cinema,” Halle Berry shared with ESSENCE ahead of his death. “He was a real pioneer, a trailblazer, and I know everyone in the community has always looked at him that way.”

This stance included paying attention to the finest details, which may have been small to the mainstream, but major to us. The iconic braids of Janet Jackson in Poetic Justice was a collaboration between the director himself, Jackson, choreographer Fatima Robinson, and dancer Josie Harris. The latter two had both previously worked with Singleton when he helmed Michael Jackson’s “Remember The Time” iconic music video, starring Iman and Eddie Murphy. This hair would become a character in itself as we watched the journey of Justice’s healing being open to a transformative road trip experience, open to new love with Lucky, played by the late Tupac Shakur, and showing up for her best friend, ultimately helping her to start new again herself.

In the hood cult classic Baby Boy, we watch as Black women take on the ever-familiar role of being the family’s backbone as the central character Jody, played by Tyrese Gibson, attempts to get his life together. We see his girl—during a break out performance from Taraji P. Henson—and his mother (AJ Johnson) go through his ups and downs as he navigates manhood.

While the film received backlash for its depiction of women, it was an all too familiar—yet not widely told—story of our strength at work, even in the toughest of circumstances. But it allowed us to see an older single mother find her joy and a young woman setting boundaries for herself. That energy even translated into the real lives of the actresses who also had to tap into that inner power. “When John asked me to do Baby Boy, John believed in what I could bring more than I did,” Johnson shared in remembrance of him on Instagram.“I was scared—strong but insecure—confident, but unknowing. He said ‘Good, this is not AJ the chem[istry] major from Spelman; she has no place here. This is Juanita. She’s loving, but scared. Smart, but unsure.’ I said, ‘That’s me for real and I don’t think I can do this.’ He said, ‘That’s exactly why you’re playing her.’”

Taraji P. Henson undoubtedly made her mark in the role, but it was 2005’s Hustle and Flow that turned her into an Academy Award nominee—a moment that would not have happened without the backing of the famed producer. Singleton used his Los Angeles home as collateral to secure the loan that allowed him to personally finance the $2.8 million production budget for the movie.

It was a bet that paid off big time and became a shining trophy for the film’s protagonist, Shug, a pregnant prostitute turned singer, who had spent her life navigating the stacked odds that resonate with Black women living and surviving in America’s ghettos. Her life is marked by pain, but it’s that pain that gives her power. When DJay (Terrence Howard) pushes Shug to give a song her all that power is revealed. (That song also ultimately gifted Three Six Mafia their Oscar award for “Hard Out Here For A Pimp.”) It was also the minute that Henson’s life began to change—a shift made possible by Singleton and the value he placed on showing every side of Black female characters on screen.

Poetic Justice was the feature film debut of Jackson and Regina King, ushering in the beginning of two extraordinary careers. Baby Boy gave Henson and Johnson a chance to validate their shine and depth, but that’s just the tip of iceberg. His work introduced us to a new dimension of untold Black woman strength onscreen at a time when no one else—aside from Spike Lee—dared to tell our tales.

Singleton won’t just be remembered for the way he made space for Black lives onscreen, he’ll also be remembered as an advocate for our stories, too.