I’m not good at asking for permission.

When I tell the young women I mentor, “you don’t need permission to lead,” I mean it. That mantra defines why I became a prosecutor, why I ran for San Francisco District Attorney and California Attorney General.

I ran for elected office so I could be in charge and use the law as a force for change. When you are in charge you don’t have to ask permission to do the right thing.

There’s no doubt that our criminal justice system is flawed. For years so-called leaders have tolerated a broken system that deems being Black probable cause, rips families apart and uses our tax dollars on private prisons instead of prevention. There is no doubt we have long been a country that exacts ‘justice’ depending on the neighborhood you live in, the color of your skin and your socioeconomic status.

I went into the system to change it.

As a line prosecutor in Alameda County, I specialized in prosecuting sex abuse cases. I spent a lot of time in Oakland’s Highland General Hospital talking with rape victims—young girls, elderly women and kids who’d been abused by people they trusted and loved. At the time, the hospital was drab, with no life in it, and musty.

Beyond the process of talking to them about what had happened and asking them to open up about painful moments, I looked around and thought, ‘A person who is already traumatized shouldn’t have to spend hours in a place like this.’ So I took action. I got a few friends together, formed a volunteer auxiliary group through the Alameda Co. prosecutors office and we painted and installed artwork to ensure that a room that sees survivors of indescribable trauma doesn’t reflect that horrific experience.

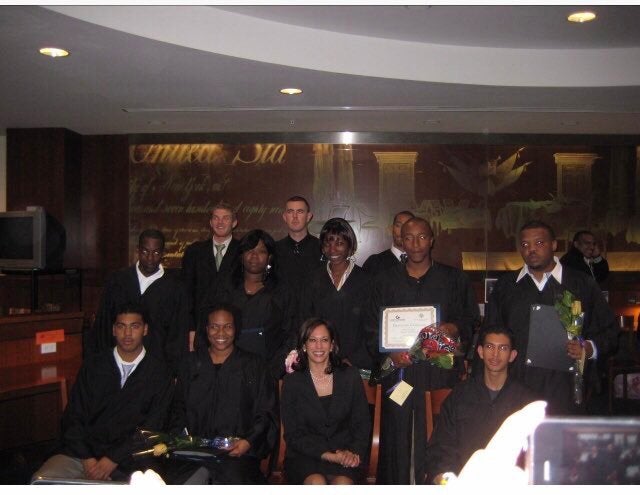

Being a prosecutor cannot be solely centered around punishing those perpetrating crime, but instead, finding ways to support survivors. Supporting survivors is why as DA, our office started the Support for Kids and Youth Program in 2005 for child witnesses or victims of family violence – the first of its kind in the state—to provide therapy and counseling in order to improve outcomes for children exposed to trauma. Further, we worked to get the city of San Francisco it’s first safe house for girls and young women trapped in a cycle of sexual exploitation and incarceration. It was a safe place for them to live, attend school and work with counselors to become everything I knew they could be.

Seeing people for more than just their mistakes and seeing their capacity for redemption and growth is another core reason I pursued this line of work. The creation of Back on Track sought to minimize recidivism by getting men and women arrested for low level drug possession jobs instead of jail time. It became a national model for DOJ’s across the nation connecting people with job readiness training, parenting skills training, the ability to earn a GED, and connecting with employers looking to hire.

Despite its success, I remember colleagues of mine asking me, “Kamala, why are you letting people out of jail? We should be locking them up.” But, because I was in charge and didn’t have to ask permission, I directed resources to Back on Track and even got to see one of my graduates this month in Houston at the debate.

Was I able to get everything I wanted done? Of course not. Did we always get everything right? No. But at every turn I always pushed for reform and change. Leadership is owning the impact of your decisions and often times the decisions of others — but good leadership is correcting course to make progress rather than giving up the good in search of the perfect.

This campaign and my new criminal justice plan are reflections of my life as a fighter for justice in a system that has long been resistant to change. Skepticism of people who have worked within this broken system is reasonable. As the daughter of parents involved in the civil rights movement, I was born with that skepticism. But skepticism does not give me license to abdicate the responsibility I felt to champion change and do the work of justice.

We need to fundamentally reimagine how we think about public safety and prioritize creating healthy and safe communities. Thinking beyond a carceral system, we must acknowledge that safe happens when we invest in public education, public health, diagnosing and treating trauma and creating economic opportunities. We can no longer default to a flawed criminal justice system rooted in institutional racism as a way to avoid addressing societal issues such as poverty, economic depression and mental health.

That said, my plan makes the case for reform that is not only actionable but immediate, and calls on my experience of leadership without excuse or permission. We can end mass incarceration, hold law enforcement – including prosecutors – accountable, we can take profit out of the criminal justice system and, most importantly, we must protect the vulnerable and those who have been pushed aside.

We need forward looking leadership and bold plans to fight for justice and reform. When I’m president, we won’t ask for permission, we will work together to enact to transform our criminal justice system and build safer communities.