At historically Black colleges and universities, halftime is when audience members rush back to their seats for the real show. The drum majors are stars, of course, but sharing the spotlight are smiling, limber dancers with moves so big, even the nosebleeds can see every detail. They prance alongside marching bands, or in the stands, then run through pre-choreographed eight counts. The sequence is first started by a single dancer in the front, followed by the rest of the team. Stadiums have fallen silent to soak in the glittering costumes and bold flourishes.

Across generations, the evolution of the over 60-year-old artform is deeply appreciated. “I’ve watched this style of dancing grow from its original form, which included baton twirling, to what it’s become today,” Dr. Shawn Zachery, the director of the Prairie View A&M University Black Foxes, says to ESSENCE. “I was captivated by the showmanship, style, glamor and execution these teams exhibited. I continue to be extremely impressed and entertained by how the style has changed over the years.”

Conception

The original majorettes, or “Dansmarietjes” in Dutch, were carnival dancers who used batons. It wasn’t until the idea reached the American South’s high schools and colleges that it came to include a mixture of jazz-ballet and hip-hop dance.

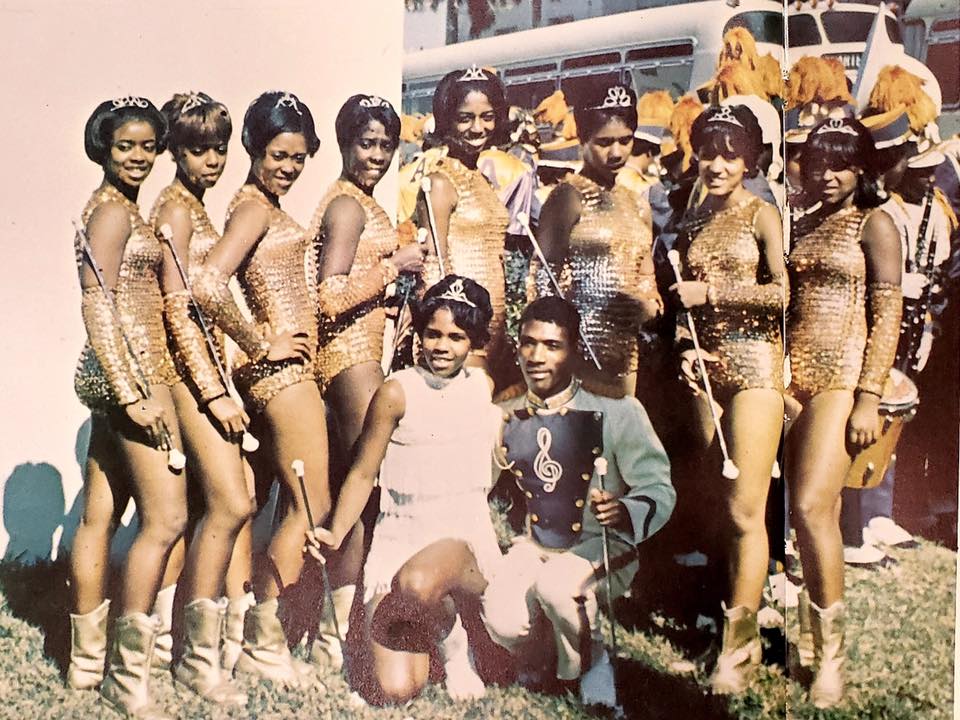

Alcorn State University’s majorette team, the Golden Girls, emerged in 1968.

According to Alcorn University, the original eight Golden Girls—Gloria Gray Liggans, Mar Deen Bingham Boykin, Delores Black Jenkins, Patricia Gibbs, Barbara Heidelberg Fox, Paulette McClain Moore, Josephine Washington Parker, and Margaret Bacchus Wilson—were the first dancers to perform a synchronized dance with a live marching band. (The exact beginning of Black, collegiate majorettes is highly contested.) The ladies made their debut at the 1968 Orange Blossom Classic against Florida A&M, with long, golden boots and gold capes.

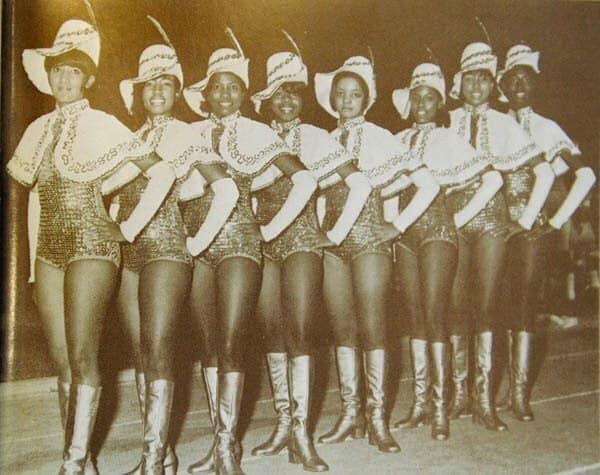

Southern University’s Dancing Dolls were introduced in 1969. Prior to requesting that Gracie Perkins, a dancer, shape the Dolls, the school’s former band director, Dr. Issac “Doc” Greggs, had gone to see the New York troupe The Rockettes. He wanted to emulate their precision and overall appeal. “He wanted pizzazz and a lot of eyes,” Perkins says. “So we had the uniforms—we ordered those from Helendale, Florida. We had the gold sequins and we had the boots.”

Perkins, the team’s founder, didn’t consider the Dolls to be majorettes (“We didn’t twirl,” she says, referencing batons), but the team presented a poise that inspired teams that followed. Perkins implemented one of the Dolls’ signature moves, the high kick, and it became a fundamental part of Black, collegiate dance teams’ choreography.

The high kick wasn’t the only new gesture in store for school dancers.

A subsect of majorette dancing known as “j-setting” was created by Jackson State University in the early 1970s. “It started in 1971,” says Cialah Jones, the current captain of the Prancing J-Settes. “The J-Sette style is really imitated all over the world from other collegiate teams and community teams. We’re really focused on high energy, cohesiveness, clean and round movements. We do a lot of acrobatic stunts.”

Getting the Look

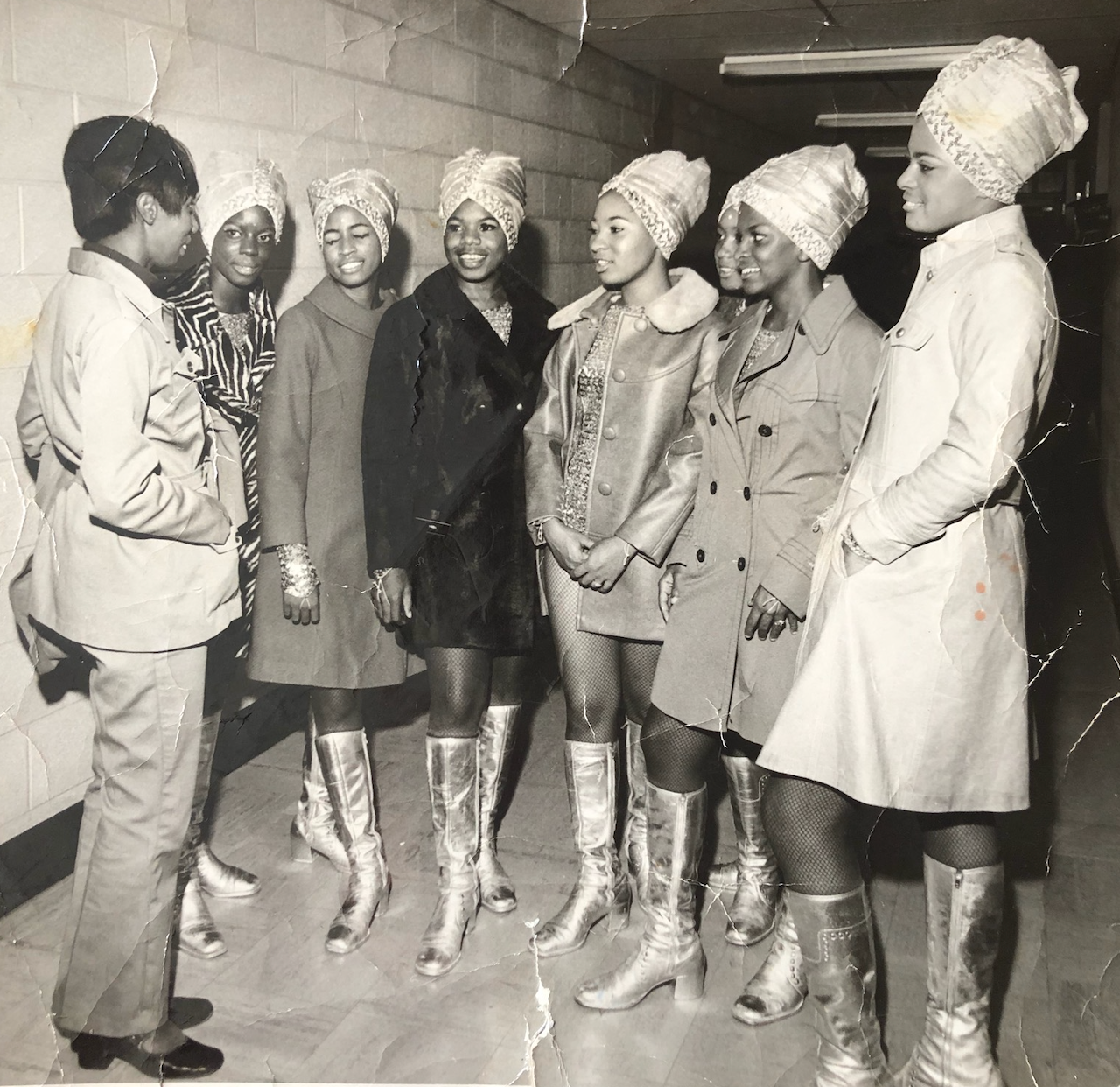

Uniforms are just as much of a statement as the routines. The original Black majorette teams were known for their intricate headdresses accented with feathers and rhinestones. Instead of wearing jazz shoes, the dancers wore character shoes, which had a small heel with a strap across the top. They also donned long boots, keeping in line with current fashion.

“A lot of what we do is built upon what came before us. To completely throw it away, it’s almost like you’re kind of erasing the legacy and you don’t want to erase it.”

As for their apparel, leotards and form-fitting bodysuits are common. HBCUs’ dancers in particular are known for their glittering ensembles that sometimes feature cutouts along the stomach and body. Some one pieces have one full pant leg and are cropped on the other side.

As dance styles have continuously evolved, the costumes have demanded changes. Dancers also began to be requested in spaces beyond gym stands and football fields, so they needed outfits to accommodate the new gigs.

“[Uniforms] evolved in a sense, that’s kind of like fashion,” says Howard University Ooh La La Dance Line advisor, Princess Alintah. “I compare that to majorette style. When I think of fashion, I think of recycling styles. We tend to bring things back from the ’90s or the 2000s and, you know, wear them again.”

When majorettes began to drop their batons, some began to trade in their character heels for more traditional dance shoes. They’re more suitable for turns, leaps and high kicks on football fields. However, you may still see some teams sporting the classic heels during the elaborate football game entrances.

Melaneice Gibbs, the coordinator and choreographer of the Sophisticated Ladies of Tennessee State University, says majorettes still hold on to these historical aspects to pay homage to the original girls.

“A lot of what we do is built upon what came before us,” she says. “To completely throw it away, it’s almost like you’re kind of erasing the legacy and you don’t want to erase it. You just want to continue to build on it and preserve some of it.”

Many teams also continue to use glitter, fringe and statement gloves. While this is all appealing to the eye, these accessories have purpose. Alintah says the fringe and glitter is to emphasize the moves and make them appear bigger than what they already are. It’s all about ensuring everyone around can see and feel the movements from wherever the dancers are.

Early Impact

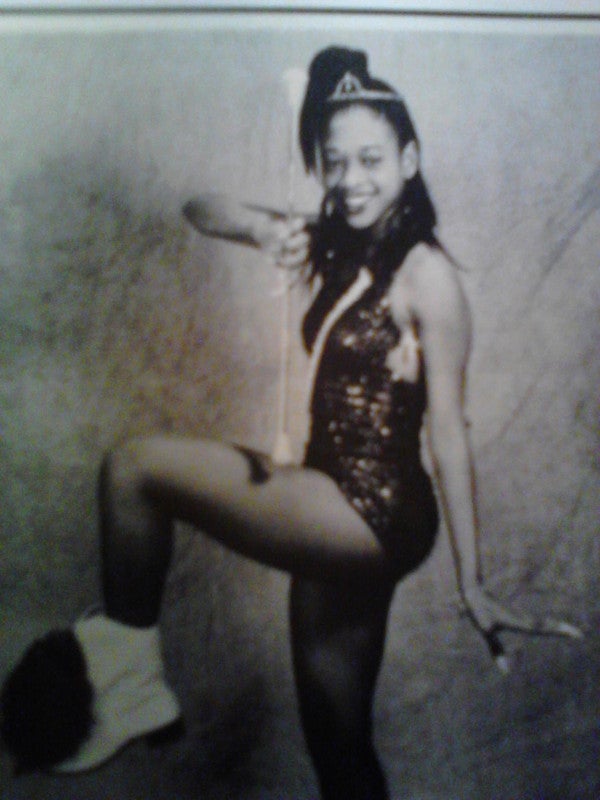

High schools, colleges and universities across the south began to debut their own majorette teams, sparking a new renaissance for Black, sports-related entertainment. One high school that joined in was Florida’s Miami Northwestern Senior High, where a young Trina was a student. She looks back on her baton-twirling days with joy.

“I really enjoyed being a majorette my entire high school years,” the rapper says. “I just remember practicing every chance I got and anywhere I went, I took my baton. I was front line so I was always ready to show up and show out!”

Batons are usually the differentiator between majorettes and dance troupes. But some teams still consider themselves majorettes, even if batons were never a part of their approach.

In addition to j-setting, the J-Settes had introduced another new idea: no more batons. Leaving them out of routines created more room for dramatic arm gestures and “bucking,” a move that involves hip thrusts and sharp arm movements.

“The majorette dance style is a very unique mixture of stunting, marching, [and] energetic fast clean movements rooted from the Southern areas of the United States,” says Dayjasia Wright, the captain of the Golden Girls.

Dr. Zachery, a Southern University Dancing Doll from 1985 until 1987, says early majorettes “were heavily influenced by regional or local dance trends as well as things that they saw on TV, movies and stage productions.” She also reveals dancers would take inspiration from popular movements and groups, such as “dances seen on shows like Soul Train and American Bandstand.” The Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, with their sexy costumes, were an influence, too.

Evolution and Controversy

Observing how warmly people embraced majorette teams at southern universities, schools beyond the south began to start their teams in the 1980s and ‘90s. Howard University’s Ooh La La Dancers, celebrating their 40th anniversary for the 2022 homecoming season, were among them.

While the Ooh La La dancers (named after the 1988 Teena Marie song) are relatively young compared to southern dancelines, they are one of the oldest teams on the East coast. While the official dance line was established in 1982, the dancers’ presence was always felt on campus. Before its inaugural line, the dancers were finding their own style as baton twirlers and traditional majorette dancing.

Advisor and former Ooh La La dance captain, Christine Jenkins, speaks about the rich history of the dancers, alluding to how they earned their name.

“Our style is one that you really can’t duplicate,” Jenkins says. “You’ll see we have big bold moves, earthmoving shakes and ‘you’re like what is going on? It looks so cool. How do you do it?’ Once you get it, it’s a beautiful thing.”

Aalaila Jenkins (of no relation to Christine), a current Ooh La La dancer, says the team’s routines made her want to join the team. “I watched all of their features during the pandemic and fell in love,” she says. “I loved the big movements and musicality, but mostly I loved how they were different from any team I studied before.”

As Black majorettes became more common, thus more visible, controversy ensued. Conversations about whether or not the dances, and costumes, were appropriate for young Black girls, began to stir up. In one Reddit thread, users questioned if Miami Northwestern Senior High School’s costume designs were age-appropriate. Their coach, Traci Young-Byron, responded directly to the criticism via Reddit, saying other ethnicities wear similar costumes without question.

“Hypersexuality comes from us,” Young-Byron says to ESSENCE. “It comes from other Black men and women who are close minded.” She also shares that her teams’ costumes vary depending on the games, but she hasn’t changed outfits to conform to the criticism.

Depending on the college or university, j-setting has also been accused of coming off seductive and sensual. But for young Black women, bucking is not sexual, it’s a way to acknowledge their roots. “We’ve been bucking and booty shaking and getting lower since the beginning of time,” Young-Byron says. “It’s how we celebrate culture.”

Physical Representation Matters

Over the past two decades, majorette teams have become more inclusive in terms of physical representation. In 2002, Edward Waters University developed the first plus-sized dance squad, Purple Thunder. Two years later, Dr. James Oliver, Alabama State University’s marching band director, had the idea to feature five plus-sized dancers during a halftime show, effectively creating the ASU Honey Beez.

“I didn’t want [the Honey Beez] to do controlled dance or modern dance,” Dr. Oliver says. “I wanted them to give me the club dancing, what they do when they’re having fun. And that’s what they did. So I started working with them myself. For the first five years I was there along with them.”

The Honey Beez initial performance was meant to be a one-time, one-minute-long occurrence. When they received thunderous applause, Oliver knew they had to continue. “Plus-sized women have always been put in the back because of their size,” Dr. Oliver continues. “I didn’t want to do that anymore. I wanted to put them out front. It was just a trial in the beginning. But it got a standing ovation.”

But not everyone was pleased. When Dr. Oliver returned to his office after the Honey Beez’s debut, he had multiple voicemails from disgruntled viewers.

“I had gotten phone calls and a few emails that said it was a disgrace to have them out there. It took me a minute to really get that to [sink in], because I couldn’t understand why it was a disgrace when they were just dancing?”

The hate didn’t stop him from developing the team and nearly 20 years later, they’re still going strong. The ladies have been featured on shows like The Steve Harvey Show, America’s Got Talent, and in Nike’s 2019 “Dream Crazy” campaign. A former captain of the Honey Beez, Asia Banks, is one of Lizzo’s background dancers, “The Big Grrrls.”

“I first became captain of the Honey Beez in 2018,” Banks says. It was her third year on the team and there were a multitude of new responsibilities on her plate, including teaching teammates how to do majorette makeup, stepping in to assist with hair, being available to talk through routine ideas with the coach. She also became a source of encouragement for her team, leveling with the dancers about being plus-sized in what she calls a “skinny world.”

“It was a dream come true because I was able to lead a group of women who hadn’t been confident enough and be a part of their confidence growing,” she adds.

Banks remained in the role until her senior year in 2020. Now, she’s celebrating her first Emmy win for her work on Lizzo’s Amazon series, Watch Out for the Big Grrrls.

Hitting Eight Counts—and the Small Screen

In 2001, Coach Dianna Williams, a Jackson, Mississippi native, founded the famous Dancing Dolls (not to be confused with Southern University’s Dancing Dolls). Thirteen years later, Lifetime began airing Bring It!, a reality show following Coach Dianna and the team as they practiced for and performed “stand battles,” a newer subgenre of majorette dance battles.

“A stand battle is a face off between two dance organizations where eight counts, 16 counts or even full routines are tossed back and forth,” Williams says to ESSENCE. It emphasizes the competitive nature that has existed in majorette dancing since the early days. Similar to the arguments around which school established the first official majorette team, universities have serious passion about which school has the best band and dancers.

While Coach Williams did not create stand battles, Bring It! popularized the form of competitive dance in not only the south, but across the country. She also believes her show has had an immeasurable impact on the fascination with majorettes.

“I honestly believe that my television show, Bring It!, created a worldwide frenzy about African-American majorettes,” she says. “We all knew about the SWAC, which is the Southwestern Athletic conference. We knew about HBCUs. But the world was not talking about majorettes the way they are now until Bring It! came on television.”

The rise of stand battles and majorette style dancing has caught the attention of other mainstream artists such as Ciara and Megan Thee Stallion.

For Young-Byron, she believes this has contributed to the always-growing buzz around majorettes. “What’s making majorette style dancing so popular is so many musical artists embracing and putting it out on their platforms,” she says.

Majorettes in Popular Culture

Beyoncé’s historic 2018 Coachella performance gave overdue flowers to HBCU culture—which of course included tributes to marching bands and majorettes. During the halftime-esque segment of the show, Nigerian dancer Diddi Emah hit the stage, strutting in a sparkling, custom Balmain costume, while twirling a baton. “It’s still surreal,” Emah says.

Although Emah is not an HBCU graduate, she comes from a family full of Spelmanites and Morehouse men. Like many Black kids in the South, the Atlanta native longed to go to an HBCU. But because of her entertainment career, she chose a more flexible route at Georgia State University.

“Luckily, when I was in high school, I joined a band camp that was all of the Black schools doing one summer camp,” she told ESSENCE. “I’m so grateful to be a part of the history of putting [majorette style] on the stage for the world to see.”

Enrollment in HBCUs has been climbing since Beyoncé’s performance. With the registration on the rise, majorettes began to reclaim their spot as America’s sweethearts. Also embracing the digital era, Black colleges and universities posted their performances on social media channels and YouTube, gaining more attention with every click.

In 2021, Howard University’s Showtime Marching Band and the university’s official majorette line, the Oh La La Dancers, were invited to escort Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris, a Howard alumni, to the 59th presidential inauguration.

What’s Next

As HBCUs have attracted more students, the cost of attendance has soared. For some people, these schools are now unaffordable, but that hasn’t meant the culture hasn’t been brought to other spaces.

“The main goal for us is to continue to showcase the history and the beautiful culture of Black dance.”

Princess Isis Lang recently broke the internet with the debut of her majorette dance team, the Cardinal Divas, of the University of Southern California. The viral move led to coverage on ESPN, Andscape, The Washington Post and a slot on The Jennifer Hudson Show.

The creation of the all-Black majorette team at a PWI revived the heated conversation about gatekeeping Black and HBCU culture. People have also wondered about the majorette team’s fate once Lang graduates in 2023. She says her focus remains on building on the strong legacy of majorettes before her.

“The main goal for us is to continue to showcase the history and the beautiful culture of Black dance,” Lang says. Saweetie, who was once a dancer at San Diego State University, and Dianna Williams, have publicly supported the team.

With new teams developing and possibly more fascination in them than ever before, the future is brimming with possibilities.

“I believe we’ll start to see even more exposure on national stages,” Dr. Zachery says. “We already have many former dancers who are now dancing professionally and making their mark in various arenas. I believe we’ll see even more creativity from our teams as our members start to come from more diverse places. We’ve already proven that we can do things they said weren’t possible on a football field or stadium floor.”

Cialah Jones closes with why she thinks majorettes and Black dance lines have the hearts of so many. “I believe majorettes are so loved and respected because of the hard work and dedication we put in every week, along with the band,” she says. “We balance college life with long practice hours. No matter how tired we are, every Saturday or every game performance and pep rally, we smile and have high energy. We just push through and I’m happy that people are starting to understand that we work really hard, just as hard as the athletes.”

Since the first time Alcorn’s Golden Girls slipped on their metallic marching boots, majorettes and dance troupes have used fashion, sass and an amalgamation of contemporary dance genres to spearhead a movement. Now, although they’ll always be linked to historically Black colleges and universities, majorettes have become a global force and are welcoming Black women wherever they are.