In 2018, the FBI reported that hate crimes on college campuses have risen 25 percent from 2015-16 and risen 17 percent from 2016-17. An additional 27.6 percent of the crimes dealt with intimidation tactics. Effecting the mental health of students of color on campuses, many of them have stated they have shifted their focus from their education to looking over their shoulders.

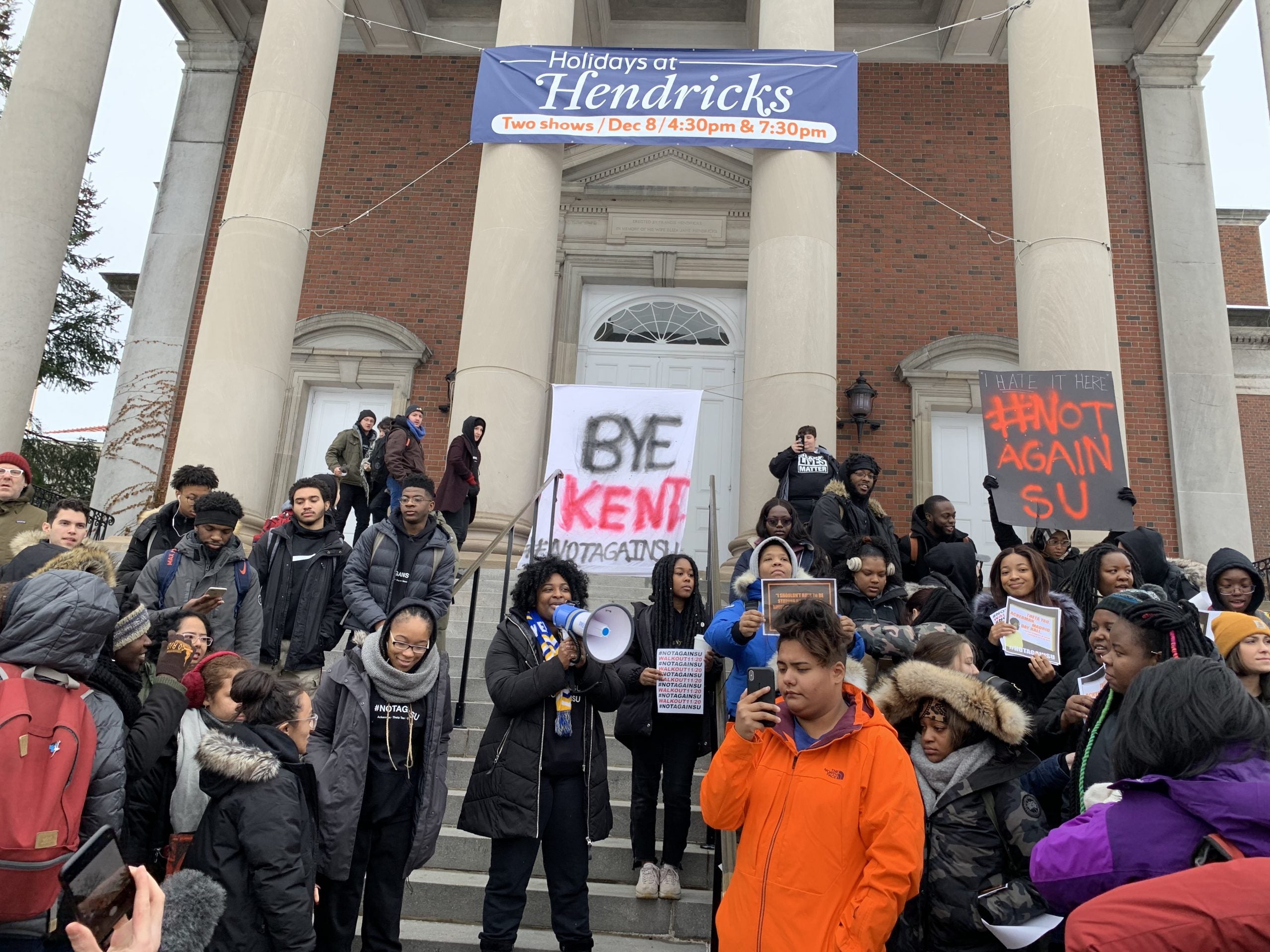

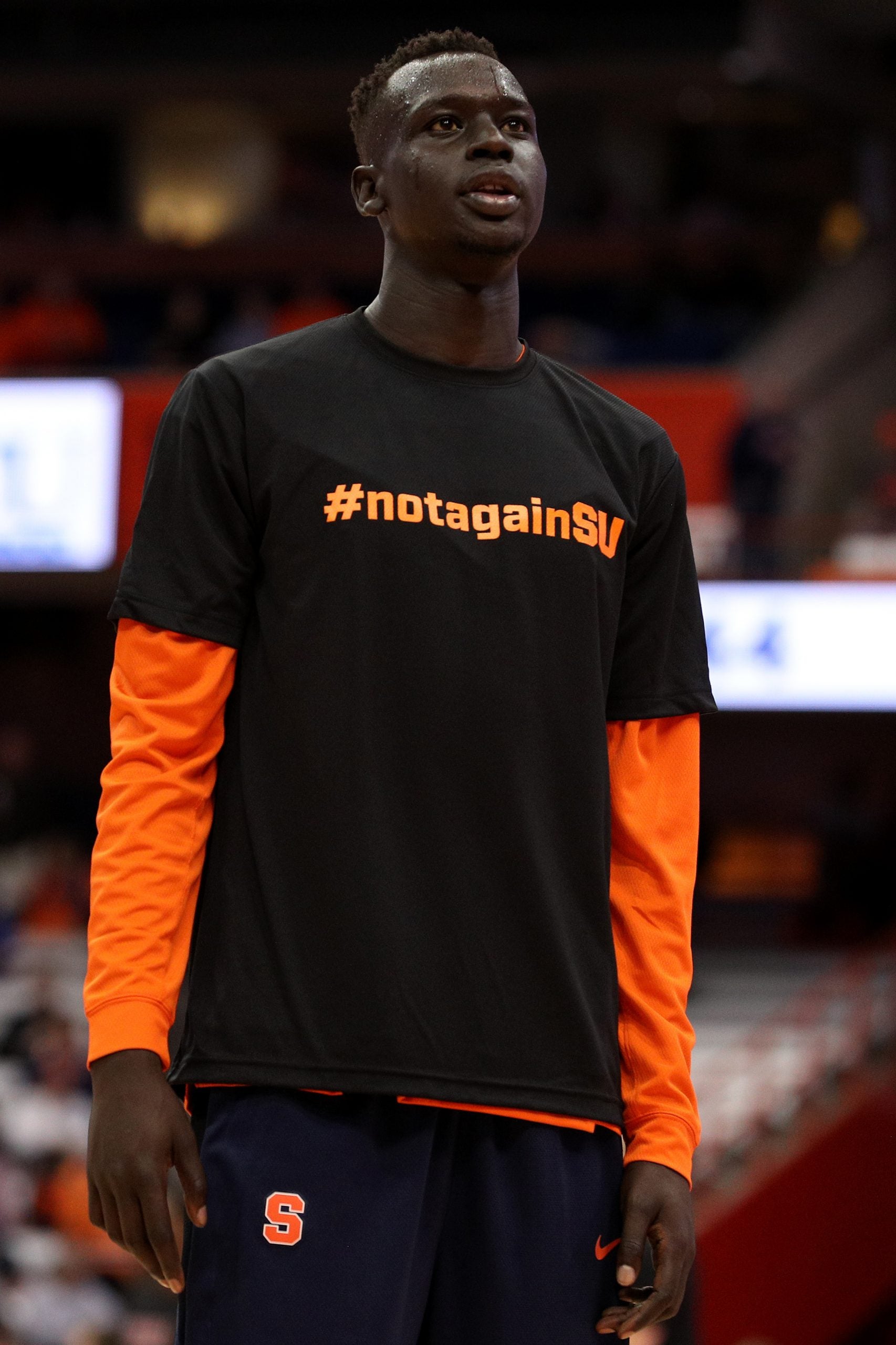

At Syracuse University, students created a movement called #NOTAGAINSU along with a list of demands for a more inclusive, safe and diverse campus. Dating back to last week, the university movement is in an uproar as racial incidents have occurred on a consistent basis, causing students and even staff to protest on campus. The Chief Diversity and Inclusion Officer, Keith Alford, released a statement saying, “Syracuse University condemns racism fervently and unequivocally. I ask that you join me in this resolve to reject all forms of bias and oppression.” Almost 30 student protesters were delivered interim suspensions for occupying a new space, Crouse-Hinds Hall, an administrative building, after hours, on Feb. 17. The suspensions have since been lifted.

Since November, Syracuse University has experienced acts of racism beginning with graffiti spotted on campus multiple times. These racial acts have been targeting Blacks and Asians. Additionally, swastikas were spotted, drawn in the snow outside of an apartment complex where many students reside. Due to the pattern of events and no arrests made in relation to the incidents, SU students held a sit-in inside of the Barnes Center, a health and wellness complex in the middle of the campus, for eight days.

In December, SU announced a Special Committee on Campus Climate, Diversity and Inclusion which students weren’t satisfied with, as it showed a lack of diversity.

The FBI reports have shown that from year to year, increased hate crimes are specifically targeting those of multiracial descent, African-Americans, and Jews.

A few weeks ago, Michigan State University was under scrutiny for displaying African American dolls in a campus gift shop, hanging from a tree. The university was even poked fun at, on a Saturday Night Live “Weekend Update.” The University Spokesperson released a statement, along with Michigan State’s President, Samuel L. Stanley Jr. “Though this display was created to honor prominent African Americans during Black History Month, we cannot ignore the historical context that made it exceedingly painful and traumatic to our community members,” said Stanley’s statement. “This display was unacceptable and should never have been put up. I’m sorry that this happened.” The shop has since taken the display down.

There have been many acts of racism over the years on college campuses across the country. Around Halloween, two students at the University of Connecticut were arrested for yelling racial slurs. Even at Hampton University, a historically black university, multiple campus police officers were fired for making racist comments in a group chat about its students. From 2017-18 white supremacist propaganda had risen 77 percent, and the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education keeps a record of many racially motivated incidents on campuses, but many are likely still missing.

The first day that Bailey Tate stepped foot on the campus of the University of Michigan, she was egged. She was moving into her dorm for the university’s summer bridge program immediately after graduating high school, in 2015. After her parents left, Tate, along with a group of other Black students planned to go get food. As they walked out of the dorm, three eggs were thrown at them as a car drove past, Tate getting hit with two of the three. “White arms quickly went back into the windows as they drove away,” Tate said.

Tate is one of many students of color who vividly remembers acts of blatant racism during their tenure at an American, predominately white, institution of higher learning. About an hour north from the University of Michigan, it’s clear that Michigan State University isn’t a stranger to racism, either. Alton Kirksey and Kailinn Hairston, both seniors at MSU noted a multitude of incidents on campus as well. Since entering college in 2016, Kirksey has noticed nooses placed on the doors of Black students’ dorm rooms around Halloween, as a “prank.” Hairston recalled the same situation in addition to racial slurs being in the body of a university survey and having the police called on her by a white, campus facilities worker for being in a classroom while practicing for a campus scholarship pageant. Last week at Syracuse, students of color were locked out of a campus building after #NOTAGAINSU protesters attempted to peacefully post flyers about the movement inside. “This is the most that I’ve dealt with overt racism out of the 4 universities I’ve attended throughout my higher educational academic career,” said one #NOTAGAINSU movement supporter, a female Ph.D. student in the School of Education; she wished to remain anonymous in fear of retaliation.

Beyond open acts of racism, students of color recognize indirect or microaggressions in their everyday college lives as well. Students started feeling uncomfortable because of the looks they’re given, ignorant comments being made at or toward them, and lack of representation on their campuses. Enjoyiana Nururdin, a junior at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, was upset that there weren’t any people of color on the university’s Homecoming committee, this year and the lack thereof showed. The committee released a promotional video for Homecoming with no black students featured. Members of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. – an African-American organization, were interviewed and tagged in the video, but their clip was not shown. “We apologize that the video gave only a partial representation of the UW-Madison student body,” said Tod Pritchard, Director, Media and Public Relations for the Wisconsin Foundation & Alumni Association, who currently sponsors the UW’s student Homecoming Committee. “We established new review and oversight protocols for marketing and communication pieces of student-sponsored work and we are committed to creating a workforce and culture in which all perspectives are reflected.”

A white student blamed Khaaliq Crowder, a senior at the University of New Haven, for a cover story in his university newspaper that featured Black football players kneeling – a story he didn’t write. Evan Starling-Davis, a graduate student at Syracuse, noticed the university Department of Public Safety officers following him while walking home, sporadically, over the course of three months.

As racism has been shown to be an issue that is tolerated on campuses across the nation, students have mixed feelings about the way incidents are handled but at the same time, many have gotten used to the happenings.

“I don’t believe administration takes the lives and the fight of Black students, as well as students from other historically marginalized communities, seriously. If White American students were the ones targeted, classes would have been canceled and professors would have been much more understanding,” an SU Ph.D. student said. “Students were expected to effectively pass exams and meet deadlines while their safety was being threatened. When the White Supremacist manifesto was posted on a Syracuse University-related website, the administration responded by saying, ‘there’s no real threat.’ Real threat to who?”

Joshua Moore, a 2018 graduate of Bowling Green State University, thinks that universities cover-up or essentially sugar coat these incidents to save face. He recalled a “notable” event while he was still a student: someone painted the slur, “coon” on the university spirit rock, which Moore says the administration tried to hide.

“They’ll send out an email saying it was an ‘isolated incident not reflecting its values,’ which will most likely not go into specifics of what was said or displayed,” Moore said. “This creates a situation of un-comfortability for students of color. It creates confusion and hysteria for the severity of what the action was and shows that the university cares more about its image rather than the safety of its students.” Bowling Green nor the University of Michigan have replied with a comment.

Finding no comfort in being discriminated against, some students say they are immune to bias incidents, taking away an initial shock factor that once existed.

“Honestly, I’m used to it. Having experienced so much indirect and direct racism, I’ve become numb to it,” Hairston said. “I still get upset and it does hurt me deeply when these things happen, but I am not surprised, especially with the climate of the world right now.”

One of Hairston’s mentors, Winston Coffee, a 2006 graduate of Central Michigan University, endured racism as a student as well. Now, as a college success coach and mentor to Detroit-area high schoolers through collegiate matriculation, Coffee assists his mentees in working through racism on their campuses. “I focus on empowering them to be knowledgeable about what resources are available to them on campus; reassuring them that they aren’t alone and that what they endured wasn’t right and should be addressed,” Coffee said. He said that his main goal is giving them a sounding board in the midst of the situation(s).

While Imani Thomas, a 2018 graduate of Hampton University, is an ally of supporting students of color during racially-motivated incidents, she recommends they also go where they feel comfortable. Thomas notes that her HBCU alma mater was a “safe haven” for her after transferring from a predominantly white institution. “With the current culture of this country, many white people may feel empowered to make their ideals known,” Thomas said. “I feel that black students would feel empowered learning in an environment where they won’t have to worry about someone hanging a noose on their dorm door or airdropping white power manifestos in the library.”

As these issues consistently arise, students of color yearn for solutions. Organizations like the Black Student Alliance, the Black Graduate Student Association, Student Inclusion Coalition and others are not only togetherness groups, but also fight against injustices toward minorities on college campuses. “For the last five-plus years, they have shown that they are completely incompetent and genuinely disregard the safety of every underrepresented student on this campus,” said a #NOTAGAINSU organizer during a protest. Amid hate, many universities across the country have found ways to navigate it. When white nationalist Richard Spencer was set to visit Texas A&M in 2017 for a “White Lives Matter” rally, a counter-protest was planned entitled, “Beat the Hell Outta Hate.” The White Lives Matter rally was later canceled.

The University of Kentucky has Bias Incident Support Services for students affected by racial bias. After racist incidents at American University, the university offered drop-in counseling hours for students. At Michigan State, Kirksey noted that this doesn’t happen on his campus, after a few protests, students lose the fight inside of them. “We come together for about two to three weeks, before dispersing. There’s no real follow-up,” Kirksey said.

As a push to not let their movement diminish, #NOTAGAINSU protesters at Syracuse University have called for the resignation of their University Chancellor, Chief of the Department of Public Safety and other administrators who they feel they have “failed to properly commit to and establish a diverse and inclusive campus environment,” according to the movement’s list of demands. Universities across the country must take accountability for the wrongdoings to others on their campuses and take action for the safety of their students. When these events occur, students have stated that they essentially go into hiding in fear of safety while searching for a perfect solution; but in reality, there simply isn’t one.

Kyla L. Wright is a Graduate Student at Syracuse University studying Magazine, Newspaper and Online Journalism on the Sports Communications Track.