In June, the news that 39-year-old journalist turned successful TV writer Jas Waters (aka JasFly) had committed suicide sent shock waves of sadness throughout Black media and entertainment circles. What happened? Had anyone seen it coming? Just over a month later, word that singer Tamar Braxton had been hospitalized after a rumored suicide attempt sparked more feelings of despair in our community.

That same week, comedienne and actress Amanda Seales revealed that she’d suffered a nervous breakdown in March because, she says, the pressures of fame had become too great. Braxton survived and Seales sought help through therapy, but as we see from Waters’s tragic death, these stories don’t always have a hopeful ending—which is why we can’t afford to ignore Black women when they are faced with a mental health crisis. Fonda Bryant almost wasn’t here to tell her story.

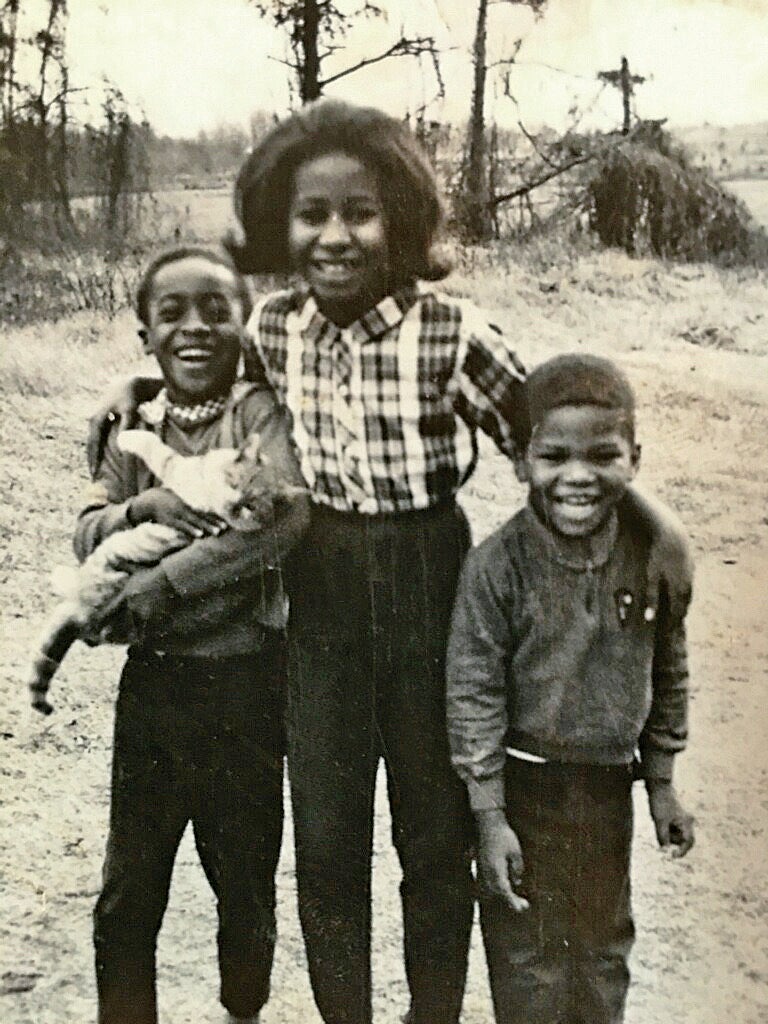

Her ongoing battle with depression and insecurity began in her early teens and plagued her throughout most of her adult life. As a daughter of an absent father (the late legendary blues singer Johnnie Taylor) who, she says, had refused to acknowledge her as his child, Bryant struggled with low self-esteem and had difficulty forming healthy relationships with men. Taylor died without Bryant ever meeting him face-to-face. Then she endured an unthinkable tragedy while in high school: Pregnant at 16, Bryant gave birth to a daughter three months prematurely.

The baby died in the hospital shortly after she was born, and Bryant was traumatized. Ignoring her burgeoning depression, seven years later, she went on to welcome a son, whom she named Wesley. But the joys of motherhood could not lift her out of the emotional hole she’d slowly and silently crept into. Bryant was around 29 years old the first time she attempted to take her own life. As a struggling young mom who was constantly at odds with her own mother, she felt overwhelmed and hopeless.

One day, tired of arguing with her mother, Bryant swallowed a bunch of pills, aiming to end her pain for good. The drugs made her sleepy and weak, but then fear and panic kicked in. She called the paramedics, who arrived to help. Thankfully, she had not swallowed a fatal dose or combination of pills, but she had raised the first red flag. Bryant’s mother took her to an outpatient facility to get help. By the late 1980s, she went to see a psychiatrist on her own. She arrived terrified and desperate for support—but ultimately left feeling even more alone.

As a Black woman, she recalls feeling a cultural disconnect between herself and the psychiatrists treating her. They ultimately released her without prescribing any medication or creating a long-term care plan—something that often happens to Black people suffering from undiagnosed mental health illnesses, due to systemic racism in health care. “They didn’t really give me any kind of help with what to do about my mental health,” Bryant recalls. “I was still out there on my own.

One of the worst things you can do when you’re dealing with a mental health condition, that can lead to suicide, is isolate yourself, because then those thoughts start getting louder. If you don’t know how to redirect them, they’ll turn into action, and that’s exactly what happened.” She tried her best to move forward, eventually even leaving Georgia to live and work in North Carolina. On February 14, 1995, Bryant, then 35, decided once again to end her life.

She filled prescriptions of the pain-relieving drugs Flexeril and Anaprox, and took steps to ensure that Wesley, who was 12 at the time, would not be the one to find her lifeless body. She made her goodbye call to her Aunt Kellie. It turns out she was calling her angel. “I don’t remember much of the conversation, but I told her she could have my shoes,” Bryant recalls. “I don’t remember what she said, but after we hung up, she called me back and asked me if was I going to kill myself. And I told her yes.”

Aunt Kellie took immediate action to try to save her niece, contacting the police and taking out a warrant to have her involuntarily committed on sight. Bryant finally began to get real help for her depression, the kind that allowed her to arm herself with better skills to battle her anxieties. She’s the first to admit that surviving was far from easy. Even as she entered her fifties, she periodically found herself battling thoughts of suicide. Her kindhearted son Wesley is the person who helped her see the good in all that she has endured. “He said, ‘What you’re going through, I know you can help people who are going through the same thing,’ ” Bryant shares. “He just nicely gave me a little kick in the pants, and the light bulb went off that day.”

Bryant is now 59, and her self-care toolbox consists of therapy when she needs it, exercise, and her volunteer work. She has become an influential and well-respected mental health and suicide prevention advocate based in Charlotte, where she serves on the local board for the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Bryant spends her time training others on how to recognize when someone has mental health issues and how to best help them cope—and who better to do that than someone who has attempted suicide two times?

In addition to speaking about suicide around the county, Bryant recently spearheaded a campaign to put suicide prevention signs in Charlotte parking decks. She also launched her own nonprofit organization, Wellness Action Recovery, with a focus on mental wellness. Bryant is on a mission to help people recognize that we can all make a difference when it comes to being someone’s lifeline and offering support when they need it most—in those moments when they’re fighting to stay with us.

For Black women in particular, there is strength in fellowship. “Black women are more likely to seek support from their friends and family than from a mental health clinician,” says Kamesha Spates, Ph.D., assistant professor of sociology at Kent State University and coauthor of the study I’ve Got My Family and My Faith: Black Women and the Suicide Paradox. “Now think about the power in that,” Spates continues. “We are more likely than our White counterparts to go to a friend or family member.

So that means when we start to talk about things like social stigma, and the issues around mental illness or suicide in the Black community and among Black women, we really have a unique opportunity to equip other Black women, and Black families and community members, with information that could literally save a life.” Too often admission of struggling with mental health issues is seen as weakness in our community. For some, admitting they need help takes away from the illusion of being a strong Black woman. According to a 2018 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the United States, with an estimated 1.4 million attempts.

While men are 3.6 times more likely to die by suicide than women, women are 1.4 times more likely to attempt suicide. It’s true that the suicide rate among Black people is significantly lower than that for other races, but even one life is too many. “We can’t talk about suicide as just this overall general topic, because the Black community is so very diverse,” explains Spates, who says she’s been studying Black women and suicide for more than ten years. “There are so many different subpopulations within the community that it’s very difficult to speak about the issue of suicide using blanket terminology.”

We have a tendency to ask people how they’re doing, instead of how they’re feeling, and there’s a difference between the two.”

—KESHIA GINN

And just as with so many other risks and diseases we face in this world, the needs of Black women are unique. “Black women’s cases, their experiences with suicide, some of the risk factors that appear to be present and some of the approaches that appear to be more helpful for Black women may not necessarily be the case for other members of the Black community,” Spates notes. “Yes, our Black women’s suicide rates are low, lower than other groups’, but I think there are some areas where we could certainly raise awareness, because it’s definitely happening. And the impact of the legacy of suicide is a whole other conversation after one occurs.” But how do we know the right moment to step in? Put another way, how do we know when to overstep for the right reasons? How do we show up for our mothers, sisters or other loved ones at a time when their well-being may be most at risk?

When a loved one is slow to respond to texts or to return a phone call, it’s easy to assume they’re just busy, like so many of us. But sudden behavioral changes like these can be a sign that trouble is brewing. Bryant recommends looking out for personality changes that seem out of character with someone’s usual routine. “They’re withdrawing; they’re not the same person,” she says. “Things that they found pleasure in, like going to the gym, taking yoga or going out with girlfriends—all of a sudden, they don’t want to do that anymore.” Speaking up during these times is crucial in getting them help. But how you reach out matters, too. “We have a tendency to ask people how they’re doing, instead of how they’re feeling, and there’s a difference between the two,” explains Keshia Ginn, a licensed clinical social worker and president of the Mecklenburg Mobile Crisis Team, a 24/7 crisis intervention program in Charlotte.

“If I ask how you’re feeling, I’m probably going to get more of what is authentically going on with you right now—if you’re feeling sad, if you’re feeling great, if you’re feeling tired. I’m going to get a more accurate picture of what’s going on with you than if I just say, ‘How are you doing?’”

When it comes to Black women checking in on one another, it’s critical that the conversations meet her where she is. Often a good starting point is the church. “Given the number of Black women who make up our church congregations throughout the country, we need a combination of every [strategy] that could happen in the church,” Spates insists. “We need conversations, we need workshops, we need gateway or prevention-based training.” She recommends that the focus of these ongoing conversations be grief recovery, addiction, divorce and those sorts of issues. If you identify someone in your life who may be having suicidal thoughts, knowing where to get help locally is also key. “We can find any and everything online right now, and most counties and cities have mobile crisis teams,” says Ginn. “Typically, they’re 24/7, and there’s an 800 number you can call. And there’s always the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, 800-273-8255. That’s an extremely important number. But first, we have to recognize the signs.”

As Bryant works hard to dismantle stigmas surrounding mental health in Black communities, she believes what’s most important to understand is that for those suffering, the journey will be a marathon, not a sprint. “Every day that I wake up and every day that I make it through, it’s a blessing,” she admits, “because I’m still not out of the woods. When I speak to students and others, I let people know it’s a battle every day— but it’s a battle I expect to win.”