When I was a kid, my mom made the mistake of placing a TV with cable in my bedroom. I was already digesting too much “adult” content, but my impressionable brain was introduced to Showtime, Cinemax (aka “Skinamax”), and HBO, allowing me to see films that weren’t meant for a boy my age. I enjoyed a lot of different genres — action, horror, political thriller — but it was romance movies that captivated me.

As someone who grew up with White pop culture surrounding him since forever, movies such as Seems Like Old Times (with Chevy Chase and Goldie Hawn) and When Harry Met Sally (Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan) were genuine favorites, but didn’t relate to my life in any real way. It wasn’t until I saw Boomerang and House Party where I saw characters of color who were cool, funny, and loved each other in a way I felt best resonated with me. Fast forward 20-plus-years, and the evolution of Black romance movies have impacted myself, others, and the big screen in a major way that promotes love, union, and heartbeat-raising moments sans needing the Tyler Perry struggle.

This Valentine’s Day winning week finds Stella Meghie’s The Photograph opening in theaters to high anticipation. Starring Issa Rae and Lakeith Stanfield as two lovers whose story intertwines with the former’s late mother, The Photograph kicks off a new decade of Black romance movies that promise less bad wigs and more sincerity when it comes to matters of the heart. While the past five years have found the genre wholly shifting from prick-dominated pictures (think Mel Gibson’s What Women Want) into women-prioritized productions, forward-thinking filmmakers such as Theodore Witcher, Reginald Hudlin, and Gina Prince-Bythewood helped to build the bridge to the Black romance boom in the late-80s, early-90s. “The primary ingredient for success in this genre is the same as it’s ever been,” Love Jones architect Theodore Witcher said to ESSENCE via email.

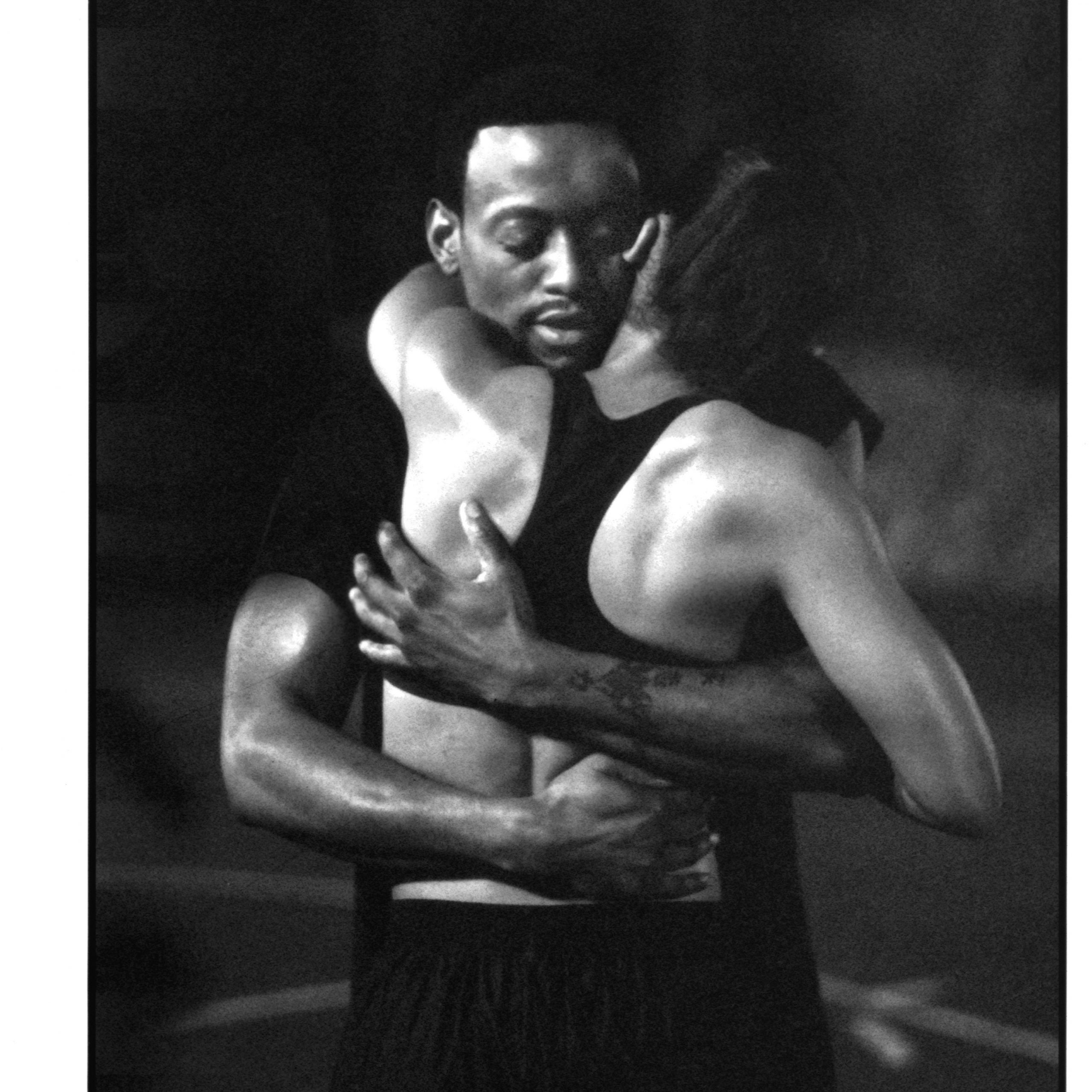

And it’s not exactly a genius insight: “The dynamic between the two leads. You may call it chemistry or heat, or whatever… but for the movie to work, the audience must become entranced by those two characters becoming a couple.”

The impact of Mr. Witcher’s Love Jones can still be felt today, with Larenz Tate showing he could go from a street life terror O-Dog in Menace II Society to a revealing and sensitive suitor as the Chicago poet Darius Lovehall. Elements such as this and the usage of comedy as with Boomerang and Waiting to Exhale worked because, according to ReelReview critic James Berardinelli, “the textures are much different than that of most mainstream romances.” A point that Black audiences have noticed since Nothing But a Man and Claudine: we are only as sexy as the struggle that confronts us, if we’re even showcased as in love at all.

“I didn’t have any [Black romantic movies] when I was young,” said writer-director Gina Prince-Bythewood, “which is why I was inspired to do Love & Basketball. Initially, I wanted to write a Black When Harry Met Sally because I couldn’t see myself in love stories.”

While penning one of the most quoted films of the early 2000s, The Best Man and Love Jones hit in a major way, setting the stage for Love & Basketball to continue that elevation by leaning into the love story aspect without the need of a laugh track. “That’s the thing we don’t often get in Black film: a true love story. And that’s what I love.”

Even when the “seriously sexy comedy” She’s Gotta Have It by Spike Lee came out in 1986, the Brooklyn filmmaker noted the disparity with how Black love was presented on screen. “Even the top stars like Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor never get to have any love interests in their films,” he told The New York Times at the time. “How often have you seen a Black man and woman kiss on the screen?”

For me growing up, it was not quite often and not without some sort of dire situation attached. Boyz N’ Da Hood and Jason’s Lyric comes to mind, but those were films where the love is driving towards a life-or-death moment that would ultimately decimate the possibility of a future. “It’s a challenge to get straight dramas made with anybody in them, let alone Black people,” Theodore Witcher wrote. “As far as romances go, how they see us and how we see ourselves contributes significantly and should be the subject of a longer discussion.”

Gina agrees in a way, “I want to be surprised. I want to go to the theater and see something incredibly different that I’ve never seen before. That’s what would excite me.” In my humble opinion, today’s filmmakers are pushing the evolutionary meter forward with films like Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk, Rashaad Ernesto Green’s Premature, and Sundance darling Sylvie’s Love, which was recently picked up by Amazon Studios, turning heads and winning awards.

This means the future of Black romance movies is extremely bright in this age of “diversity and inclusion.” As more studios and companies of color greenlight their own projects, the challenge of getting material like this through the Hollywood system seems lessened. The Photograph, which will play to thousands of screens across the country, is one snapshot at what we can expect to come in this new decade of Black creativity.

“It’s all about authenticity,” legendary producer-writer-director Reginald Hudlin shared with ESSENCE when it comes to making a romance film that stands the test of time. “You can be comedic, you can be dramatic, you can be in the hood, but ultimately all that stuff doesn’t matter. What does is that Black love is at the center of your story and that it feels real—that it is something that people see and can relate to.”

I absolutely love that.

Kevin L. Clark (@KevitoClark) is a Brooklyn-based music journalist, screenwriter and recent kidney transplant recipient, who is raising awareness about his Mighty Healthy crowdfunding project on Seed&Spark.