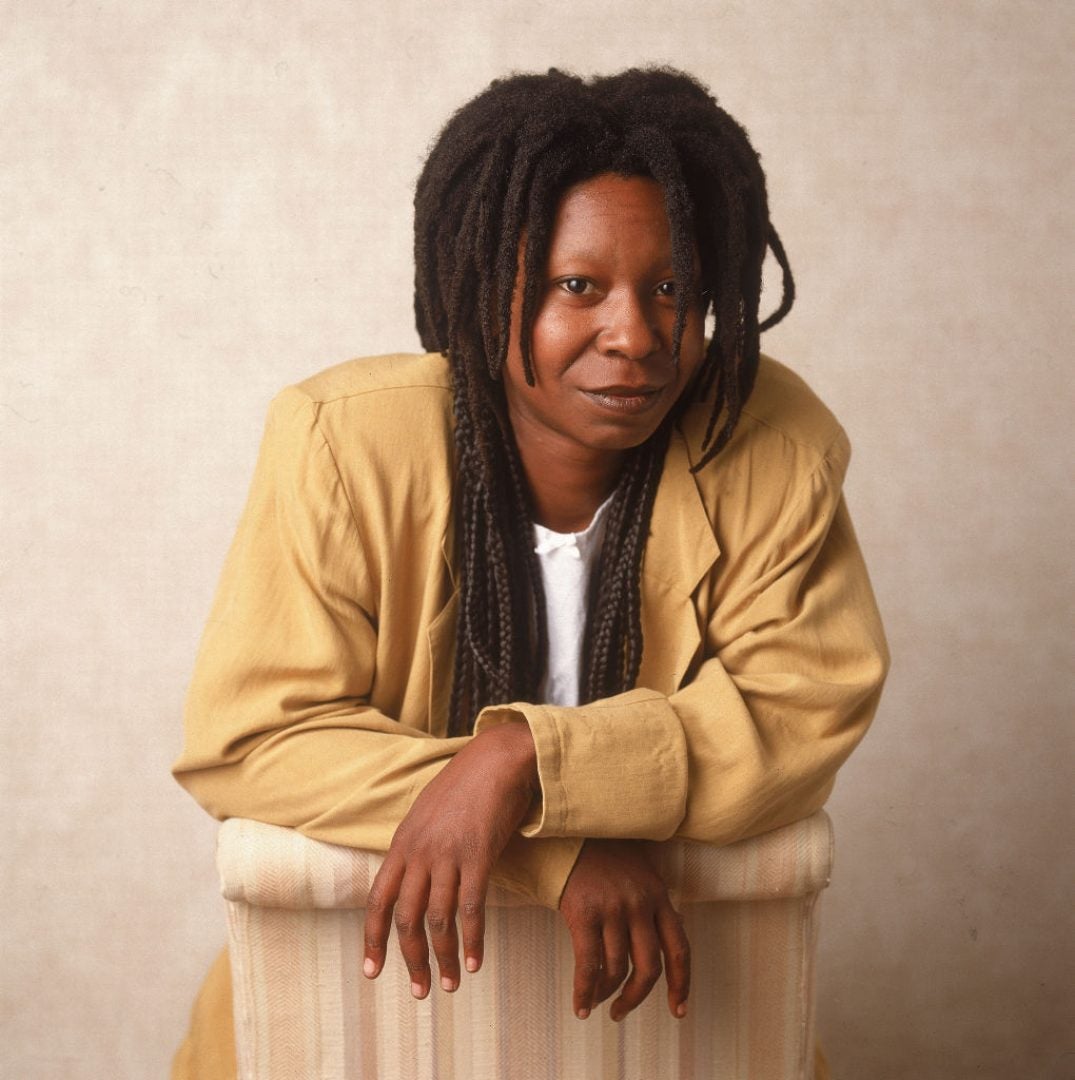

In 1984, a lesser-known Whoopi Goldberg stood on stage and imitated a little Black girl who wears a shirt on her head, pretending it’s her own long, luxurious, blonde hair. The bit, which was part of her one-woman show on Broadway, was a commentary on how inundated we were – and still are- with standards of white beauty. But somewhere along the way people seemed to get the idea that Goldberg wanted to be something other than the Black woman she is and always has been.

“Listen, I caught a lot of shit from Black people [over the years],” the 2021 Black Women in Hollywood (BWIH) Honoree tells ESSENCE. “Apparently I wasn’t Black enough, but people forget if they saw me running down the street and it’s the Klan, they’re going to chase me. That’s how I measure it, is the Klan going to chase you if you run? Yes. They’re going to chase me. That means I’m Black enough.”

That conundrum is one not often spoken of among entertainers today with many Black actors and actresses often getting an automatic buy-in from Black audiences as they spend the early years of their careers trying to prove to casting directors, major studios and mainstream audiences that they’re talented enough to be on peoples’ screens. Goldberg, on the other hand, was almost immediately accepted by the Hollywood machine – far before Black folk would get her.

“I got brought into the industry by Mike Nichols and Steven Spielberg, so there wasn’t much people could say,” she explains. “They knew I was talented, that wasn’t ever the question. Attitudinally, people had issues because I worked with two people who spoke to me as an equal, and then I worked with people who thought I was the cleaning lady and would talk to me in some kind of way. Because I’m a buzzard, I’ll be just right in your face – ‘What did you say to me?’ – in a time when you weren’t supposed to be doing that.”

It was Nichols who saw Goldberg’s standup routine in the ‘80s and brought her to Broadway where she caught the attention of Spielberg. The producer and director casted Goldberg in the lead role of Celie in the film adaptation of Alice Walker’s novel The Color Purple which today sits atop many lists in the Black film cannon. When it was released in 1985, however, the picture was picketed by a number of African Americans, including members of the NAACP, from Beverly Hills to Montgomery County. The controversy still boggles Goldberg to this day.

“You don’t see a lot of Black people in movies, in ensemble films, and here’s a great ensemble film made by a guy who probably would not have made it if someone else had stepped up, but nobody else did. And so he’s getting shit for doing it, and then we make this really good film, and then everybody’s pissed. It’s like, you did read the book, didn’t you? What did you think we were doing?”

She explains of the backlash, “It became about, first, ‘How dare he make this movie? Meanwhile, Quincy Jones is the producer, okay? They’re working together. Then it became, ‘How dare you all tell this story and insult Black men?’ And then it became, ‘This is not the Black experience.’ Well, it’s somebody’s Black experience because she wrote a book called The Color Purple. We got 11 nominations and no win because I think people said, ‘Let’s just acknowledge that they did it and keep it moving.’”

Unfortunately, what keeping it moving has looked like, from Goldberg’s point of view, is further limiting opportunities for Black people in movies. “All of that, I feel – I said that then and I say it now— put the kibosh on people putting a lot of Black ensembles together for a full-length film because nobody wanted to be told they were doing it wrong.”

In relaying her thoughts, Goldberg notes her point is a familiar one. It’s a particularly relevant one as well when you compare her experience to that of fellow BWIH honoree Zendaya. Her romantic drama, Malcolm & Marie, was highly anticipated before its January release on Netflix this year, yet when audiences learned it was written, produced and directed by Sam Levinson (Zendaya and her co-star John David Washington also co-produced the film), it became marred in controversy.

Speaking on the notion that only Black people can write, direct, and produce Black stories, Goldberg says “That only works if you go to see something and you say, ‘Well, that’s not even our experience,’ but clearly Malcolm & Marie was because everybody was like, ‘Oh my God.’ Then suddenly it’s like you discount people. You don’t know why he wrote it, you don’t know where it came from or how, and you don’t ask. You don’t say, ‘Hey, because this hooked a lot of people in, how did you get to this?’ People don’t want to hear that.”

At 65, Goldberg has seen her share of examples when it comes to films damaged by baseless commentary. For her, there’s only one hard rule when it comes to being a master storyteller. “I’m at the age where I give zero you know,” she says qualifying her next statement, “but the reality is if you can’t tell who wrote it, it’s a great film.”

The acclaimed star adds, “[Controversy] isn’t going to stop me from doing what I think is right or want to do, but it may stop [someone else] from wanting to write something that is really great. So we’ve cut off yet another avenue into figuring out how we can all exist on the planet together.”

A Woman of her word, the backlash to The Color Purple, Goldberg’s first leading role by the way, hardly stopped her from excelling on the big and small screen as well as the stage. In 1986, she became the first Black woman — and only the second solo woman performer — to win a Grammy for Best Comedy Recording, which she received for Whoopi Goldberg: Original Broadway Show Recording. She’s also the first African American to receive Academy Award nominations for both Best Actress and Best Supporting Actress. Her 1990 win as Oda Mae Brown in Ghost, combined with her 2002 Tony Award and 2009 Emmy win made Goldberg the first and only Black woman EGOT – there are only 16 total throughout the history of Hollywood.

There’s a hollow reality in looking at Goldberg’s firsts which, in many ways, expose her as the only during her time. When she received such accolades, there were no fan girl moments like that shared between Regina King and Andra Day, who became the first Black woman to win a Golden Globe for Best Actress since Goldberg did in 1985, earlier this year.

“Alfre Woodard, and, I have to say, Debbie Allen too, those were the two women who kept me bolstered,” Goldberg says, explaining there was no moment where she was embraced by the Black community as a whole for the barriers she broke.

“I looked too odd, and I knew lots of white people, and apparently you’re not supposed to. And, my God, I might have married a couple of them,” she says facetiously. “It’s only in the last 10 years have people been like, ‘No, it’s really good, man, you’re all right.’ Like, thank you?”

Asked whether she harbors any resentment Goldberg says, “No, but I don’t mind saying I saw it, I see it. I see it, I’m aware of it. I’m glad you’ve evolved. But just don’t do it to somebody else because it’s kind of dumb. And that’s the problem with not having that connection with other people because the thing that you know as an artist is that we’re all trying to do the same thing, we’re trying to make our art better, and so why not support folks?

“I’ve been a Black lady the whole time, this is my nose, most of this is my hair, I’m the same color I was because I haven’t been in the sun. This is what I’ve looked like and this is what I’m going to die looking like. I haven’t moved anything, there’s no extra back there. I have looked like a Black woman the whole time. So, all those folks that have something to say, it’s like, back up off me.”

There’s a certain dismissiveness that comes with not seeing Goldberg as Black enough that implies she’s somehow had an easy go as a dark-skinned, natural haired entertainer over the course of decades when there were no movements to garner support for such features.

“People said, ‘You changed your last name to Goldberg to get ahead.’ It’s like, get ahead? Really? You think it’s that easy? Okay, sure.”

The reality is Goldberg excelled in parts others passed over. Scoffing at the idea she would’ve said no to certain roles, she says, “No, child. Please, come on now. That may happen these days, where the sisters are turning shit down. It wasn’t like they were throwing shit at me. I took movies that other people turned down.”

When she says “other people” she means the likes of Bette Midler, who was supposed to take the lead in Sister Act, and Shelley Long, who was the initial choice for Jumpin’ Jack Flash. Burglar wasn’t supposed to have a female lead until Bruce Willis dropped out and Goldberg when from supporting to starring role.

“I don’t know what’s in people’s minds, but the work is the work, and either it’s working or it’s not, and then if it’s not, you make it better,” she says of her career trajectory. “I’m not anybody who anybody sought out for sex to exchange for roles. Nobody was coming to me for that. Nobody invited me up over to their house. No. That wasn’t my M.O. and that’s not how they saw me. They saw me as, I think, oftentimes maybe not lesser than, but not-as-good-as. And I was quite happy to be not-as-good-as because we can keep that over there.”’

Thirty-nine years after her first appearance on screen in in Citizen: I’m Not Losing My Mind, I’m Giving It Away, Goldberg speaks with an excitement about her career that one would expect from someone who just completed their first picture. When I relay that sentiment she responds with an “Oh yeah” and a smile. As the embodiment of the idea that if you do what you love you never have to work a day in your life, Goldberg says there’s never been a time in her career that she didn’t enjoy what she was doing. There was a point, though, where she tried to put a bushel over her light, as she puts it, to make others feel more comfortable with her success.

“We get into relationships with people, and suddenly now you’ve got to be less so they need to feel like more, and you get to a place where it’s like, this is a lot of work. Carrying you is a lot of work because there’s no reason why you can’t be doing what you’re supposed to be doing and get off my back so I can go do me. And then I thought, you know what? Just take your house back, take your life back, get these motherfuckers out of here, and go do you.”

That she did, three times over in fact. Goldberg was married to Alvin Martin from 1973 to 1979; to cinematographer David Claessen from 1986 to 1988; and to union organizer Lyle Trachtenberg from 1994 to 1995. In some ways, leaving those relationships was difficult, in others it was the truest way for Goldberg to honor herself.

“In the back of your mind you think, well, maybe you’re not trying enough, maybe not trying hard enough to be a good woman. And I’ve always been the best woman I could be at the time I could be it. I never promised that I was going to be any different, and I thought you knew that. I didn’t turn into this, this is what I always was. You just thought that it was a ride that you could do. It’s okay if you can’t. And I’ll even make it easier, I’m going to get off the ride, I’m getting in the car, and I’m leaving. So, that’s what I do. That’s what I did and now I’ve never been happier.”

Some women never get to a point where they can shed society’s expectations of them, even in their 60s. But Goldberg learned early on that creating a life for yourself that’s outside of the norm is okay, you just have to be prepared for what that comes with.

“My mother was really clear in who I could be if I wanted to be, and the costs of that. The costs of being an individual, the cost of looking different than other people, the cost of sounding different in other people’s minds, the cost of people’s perceptions of what being Black is and not letting them limit who you are because they don’t see the big picture.”

—

The ESSENCE Black Women in Hollywood Awards are presented by Ford and sponsored by American Airlines, Coca-Cola, Korbel and L’Oréal Paris.