When I visited my first historical all-Black town in April, someone asked the group I was with what we knew about Boley as we were on our way there. One person said they imagined it looking like an old town from a Western film. For me, the only reference I had to compare Boley to were images I’d seen from the past of Black Wall Street in Tulsa, Oklahoma. I had no idea what this historically all-Black town would look like, but I knew it would be rich in history.

As we turned onto the main street in Boley, Oklahoma, to meet up with the rest of the group participating in the Sovereign Futures experience organized by curator Allison Glenn, I was surprised to see such an empty town. During the walking tour, we visited what remains of one of the first Black-owned banks and then hopped on the bus to explore the rest of the town. A native of Boley, who was on the bus with us, took the opportunity to provide us with context about the places we were passing. She shared stories from her childhood about the local school and even pointed out the house where she grew up.

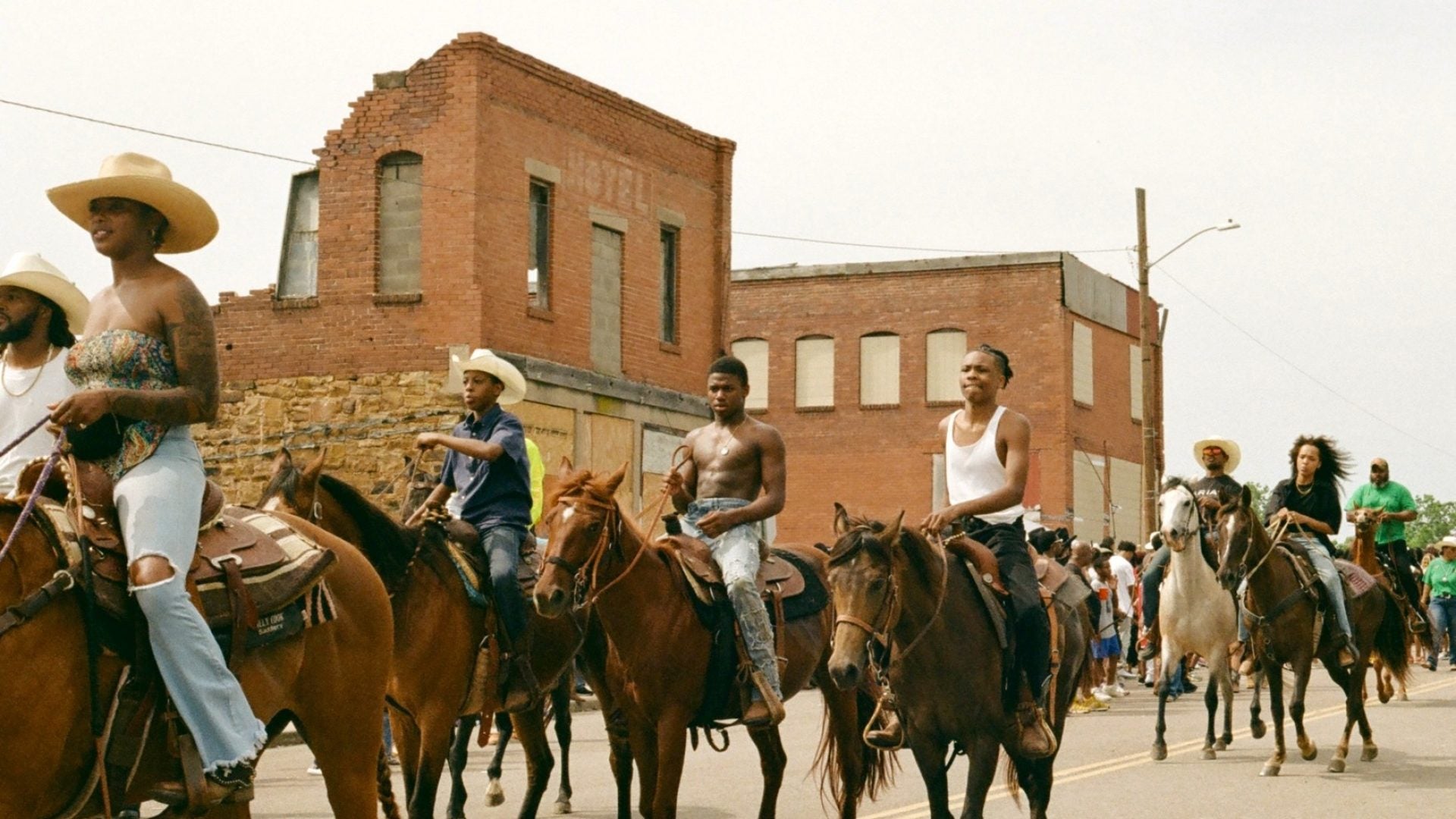

During our last stop on the tour, we visited the site of the Boley Rodeo. Although I had hoped to see some cowboys in action, I found out that the main event actually takes place during Memorial weekend every year. The Boley Rodeo has been a significant tradition in this historic town since 1903. It is a time when former residents return, and the community gathers to celebrate their love for each other and the town, which holds a prominent place in Black history.

The Boley Rodeo, which is the oldest and longest-running Black community rodeo in the nation, has become a significant event drawing thousands of visitors and fostering a strong sense of pride and unity among attendees. Karen Ekuban, an alumna of Boley and a dedicated community advocate, has played a key role in rejuvenating the rodeo through her philanthropic efforts and leadership with the Project 2020 Foundation.

“The Boley Rodeo is important because it represents history,” Ekuban told ESSENCE. “It’s a community that was self-governed, rich in history and placed great emphasis on education and opportunity. This year marked 121 years, and next year will be 122 years. Every possible year, we made sure to organize it. It’s like a homecoming for our alumni, their children, and even their children’s children. Every Memorial Day weekend, they know they’re coming home. We wanted to give them something to do all day and for the whole family. This year, we included a car show, a kids’ zone, and a concert to enhance the rodeo experience.”

Ekuban expresses the importance of her partners, Jacqueline Floyd and Ellengton Boyce, in preserving the legacy of historical Black towns. She stated, “Without these Black towns, there would have been no Black Wall Street.” This underscores the critical role of these communities in the broader narrative of Black history in America.

Allison Glenn, a dedicated curator with a history steeped in the arts, recounts her journey to Boley. Her connection to Tulsa, about an hour and a half away, began during her tenure at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. The Greenwood Art Project, a landmark event coinciding with the Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial, drew her deeper into Oklahoma’s vibrant yet painful history. It was during this time she discovered the existence of the state’s all-Black towns—50 of them, born out of the ashes of emancipation and the dreams of a Black separatist state.

“Learning about these towns was a revelation,” Glenn recalls. “I never came across their history in any of my previous education. The idea of creating a Black separatist state in the center of the country fascinated me. Visiting Boley feels like stepping into a different world. It’s a place where history isn’t just remembered—it’s lived. Every year, the community comes together for the rodeo. It’s not just an event; it’s the heartbeat of the town.”

Glenn and her team are working on initiatives to support the community beyond the annual event. From commissioning murals to addressing food deserts, their vision is one of sustainable, long-term investment.”Why isn’t there a Hattery in Boley where you can get your rodeo hat year-round?” Glenn expresses. “Or a place to get on a horse? It’s about thinking long-term and how we can support these communities through art and culture. I feel really drawn to this space. There’s something magical about it—a mix of history, culture, and community that’s unlike anywhere else.”

As I departed from Boley during my April visit, I remember feeling a renewed appreciation for the town and its people. Though my stay was brief, it left me with a deep connection to the spirit and legacy of Boley—a connection that has remained with me. While I didn’t have the opportunity to witness the historic rodeo, what I did encounter was equally significant: a peek into the soul of Boley, where history and community interlace in a fabric of resilience and hope.

Karen Ekuban expressed the overwhelming sense of pride and excitement that filled the event. “What stood out to me the most was the smile on people’s faces, the sense of pride, of excitement,” she recalled. “It just really touched me because, you know, to see alumni and their families and their kids that haven’t been back to the rodeo in years.”

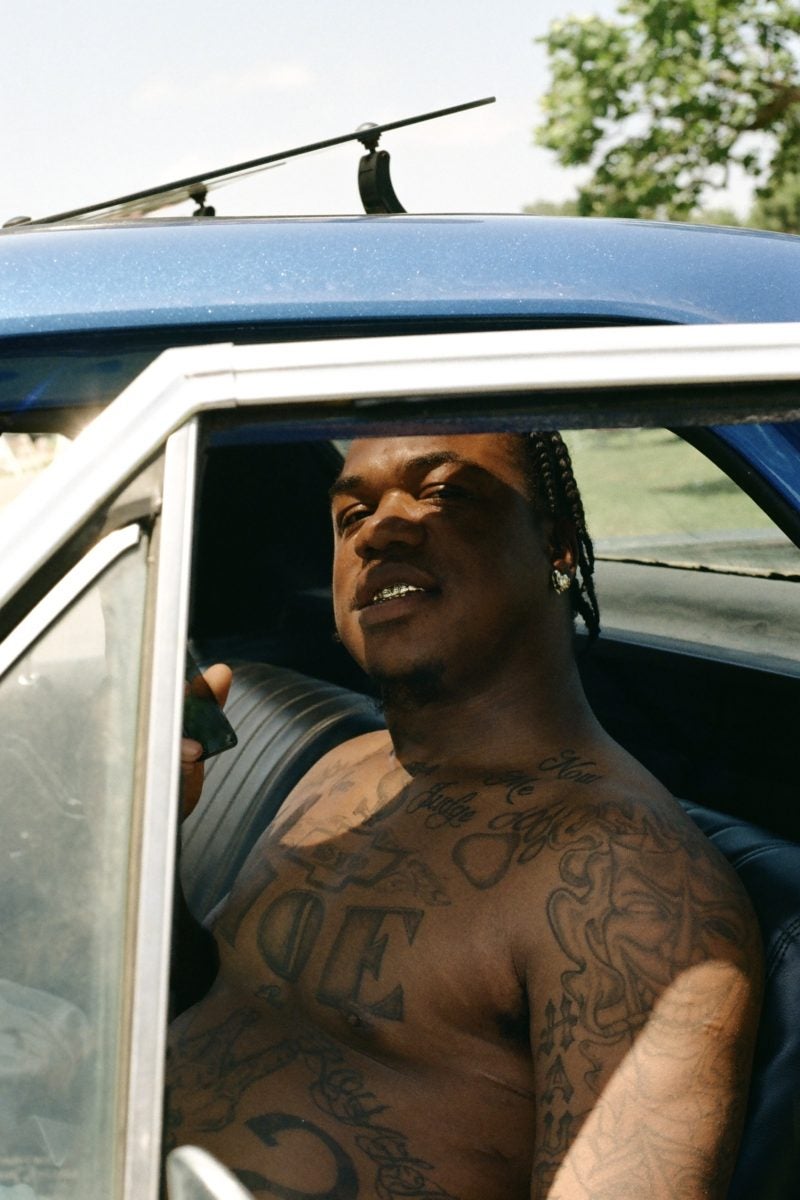

In celebration of 121 years of the Boley Rodeo, photographer and founder of the Oklahoma Cowboys, Jakian Parks, captured the spirit and style of Boley’s people. Project 2020 Foundation also shared images from the main event of the day.