Fannie Lou Hamer came from humble beginnings in Mississippi and went on to become a powerful voice in the civil and voting rights movements and a leader in the fight for economic equality for African Americans.

Hamer’s legacy lives on 46 years after she passed away in 1977. Discover more facts about the life of this trailblazer that you may not have known.

The youngest of 20 children born to sharecroppers in 1917, Hamer grew up in poverty and worked on a plantation helping her family pick cotton from the age of six. By the time she was 12 years old, she had to leave school to work full-time on the plantation and help support her family. She married Perry Hamer in 1944, and the couple worked on B.D. Marlowe’s Mississippi plantation until 1962.

Hamer’s life changed in 1962. She attended a civil rights meeting and learned about the right to vote and its importance at the age of 45. “They talked about how it was our rights as human beings to register and vote,” Hamer told the New York Times. “I never knew we could vote before. Nobody ever told us.”

From there on, she vigorously fought for Black voting rights. Although, Black people did have the legal right to vote at the time, many Southern states made it very challenging for them to register to vote.

For instance, Black people frequently had to pass literacy tests before registering. They had to read and comprehend complex government paperwork for the tests—many who attempted to register also faced violence.

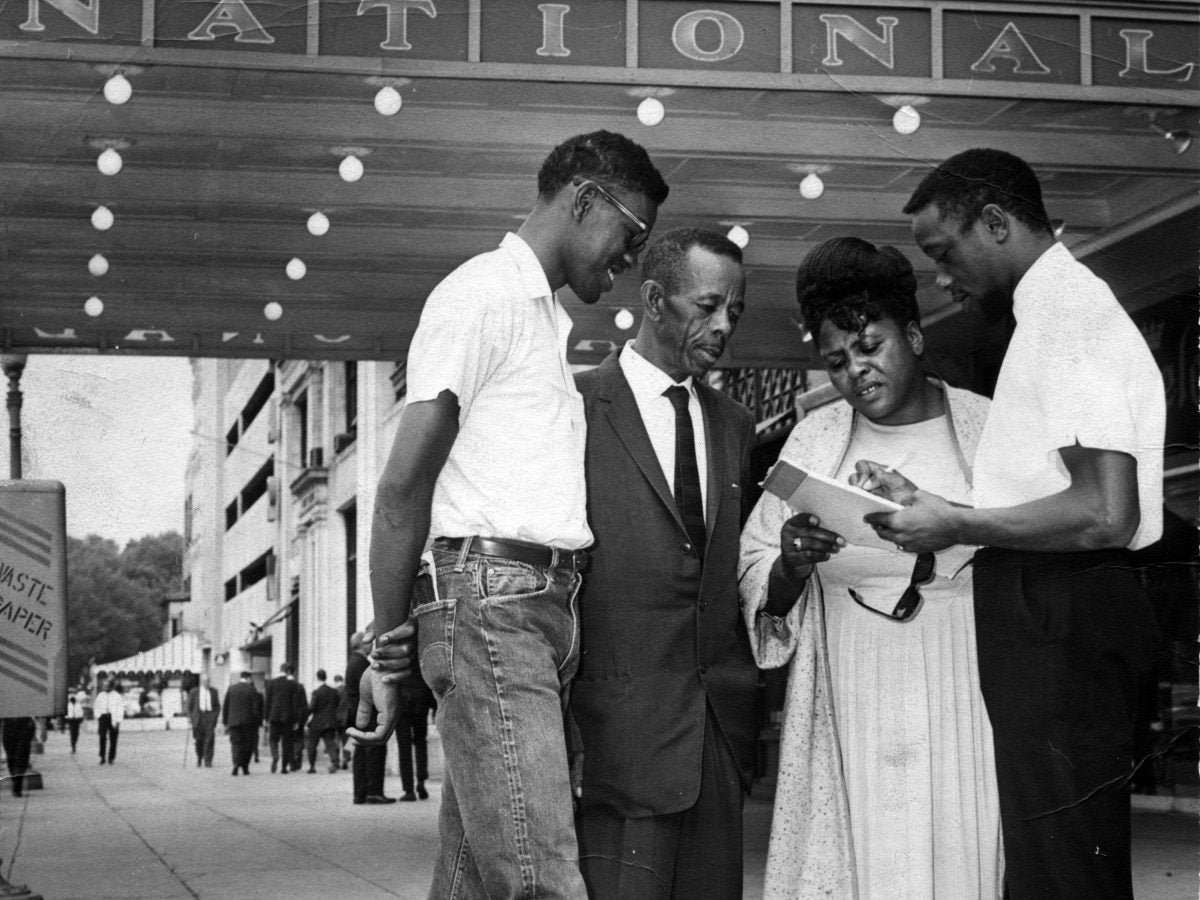

Fannie Lou Hamer became an organizer in the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP). The organization challenged the local Democratic Party’s efforts to block Black participation.

As she fought for the rights of others, she faced personal battles of her own. In 1961, a white doctor performed a hysterectomy on Mrs. Hamer without her knowledge or consent while undergoing surgery to remove a uterine tumor. The “Mississippi appendectomy” was a common practice at the time to forcibly sterilize people deemed unfit to bear children, including poor Black women. She could not have children of her own, but she and her husband adopted four daughters.

In June 1963, after completing a voter registration program in Charleston, South Carolina, Hamer and several other Black women were detained in Winona, Mississippi, for dining in a “whites only” bus station restaurant. She and several other women were severely beaten while in jail. It left Hamer with lifelong injuries due to a blood clot in her eye, kidney damage, and limb damage.

But, she remained undeterred. In 1964, Hamer helped organize Freedom, Summer in 1964, which brought hundreds of college students of all races to help with voter registration in the segregated South.

In a televised speech during the 1964 Democratic National Convention, Hamer called out American hypocrisy. “Is this America,” she asked, with tears in her eyes, “the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off of the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

But her passionate testimony almost wasn’t heard.

President Lyndon Johnson called an impromptu press conference during her speech to get TV networks to air his remarks instead. But the plan backfired. Because news outlets suspected Johnson was censoring the activist, they later ran the full speech and replayed it for days. And it helped change history.

“The United States could not claim to be a democracy while withholding voting rights from millions of its citizens. Although the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) delegation did not secure its intended seats at the convention, Hamer’s passionate speech set in motion a series of events that led to the 1965 passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act (VRA),” Smithsonian Magazine reports.

Hamer helped register voters and empowered others by entering the realm of electoral politics herself. She continued to champion Black voting rights for the rest of her life. She died at the age of 59 in Mississippi, on March 14, 1977, due to complications from breast cancer and hypertension. She was laid to rest in her hometown of Ruleville, Mississippi. Her tombstone is engraved with one of her famous quotes, “I am sick and tired of being sick and tired.