Kienjanae “K.J.” Hooper’s senior year had not quite turned out as she’d hoped. On-site learning at her East Texas high school ended abruptly in mid-March due to the deadly coronavirus pandemic sweeping the country; the cancellation of all scheduled senior activities, including prom, soon followed.

She hated being cooped up at home and away from her friends, but one bright spot was her part-time job at a local car wash. After weeks of eight-hour shifts detailing vehicles, K.J. says she eventually saved up enough money to treat herself to a special hairstyle for her senior photoshoot and graduation ceremony; long, flowy, burgundy-tinted braids. It took a stylist friend 10 hours to complete and K.J. footed the hefty bill. But it didn’t matter; she loved it.

But her one glimmer of excitement quickly faded into feelings of anger and frustration Monday. That’s when she says her principal at Gladewater High School, Cathy Bedair, reportedly called the National Honors Society-inductee and star athlete’s mom to inform her that K.J.’s braids violated the school’s dress code.

Bedair told her mother that K.J. would “have to take [them] down in order to walk and graduate” at the in-person ceremony scheduled for Friday evening in Gladewater, Texas.

“I said no ma’am; there is no reason that she should have to hide or take her hair down when she’s worn her hair [in braids] throughout the school year,” says mom Kieana Hooper, who is white. She insists Bedair referenced both her daughter’s hair color and style. “I told her, she’s not doing nothing outlandish, like blue, green, purple or pink [hair]; she just likes to wear highlights and low-lights, with a reddish tint, you know nothing out of the ordinary.”

K.J. says she’s unsure if the principal’s directives were based on race, but she feels she is being unfairly targeted.

“She’s saying my hair is a distraction. But from what?” asks the 18-year-old. “Really, the whole thing is really dumb to me, to be honest. Why does it matter about my hair that I can’t walk across the stage? I’m not going to say, ‘oh, she’s racist,’ but people have been calling her racist. Even before this whole hair thing people were saying that [about her].”

Hooper says she told the principal that she flat-out refuses to make her daughter, who maintains an A-average and also volunteers with hospice patients and special-needs children, change anything about her hair just for the ceremony. She says Bedair called her back hours later, stressing that the alleged main issue was that her hair color does not look “natural” as the policy requires.

Bedair’s “resolution? ” K.J. can walk if she tucks all of her braids into her graduation cap or inside the back of her graduation gown.

Hooper declined.

Not surprisingly, she says the situation has been upsetting to her daughter.

“I noticed that she was really closed off [that evening] and later on she came to me and says, ‘it’s no big deal, mama, I can just take them down so I can graduate,’” recalls Hooper. “And I said, ‘no, ma’am, you’re not. The point is that what’s right is right and what’s wrong is wrong.’ We have too much going on in this world, [for the school district] to be worrying about a piece of hair.”

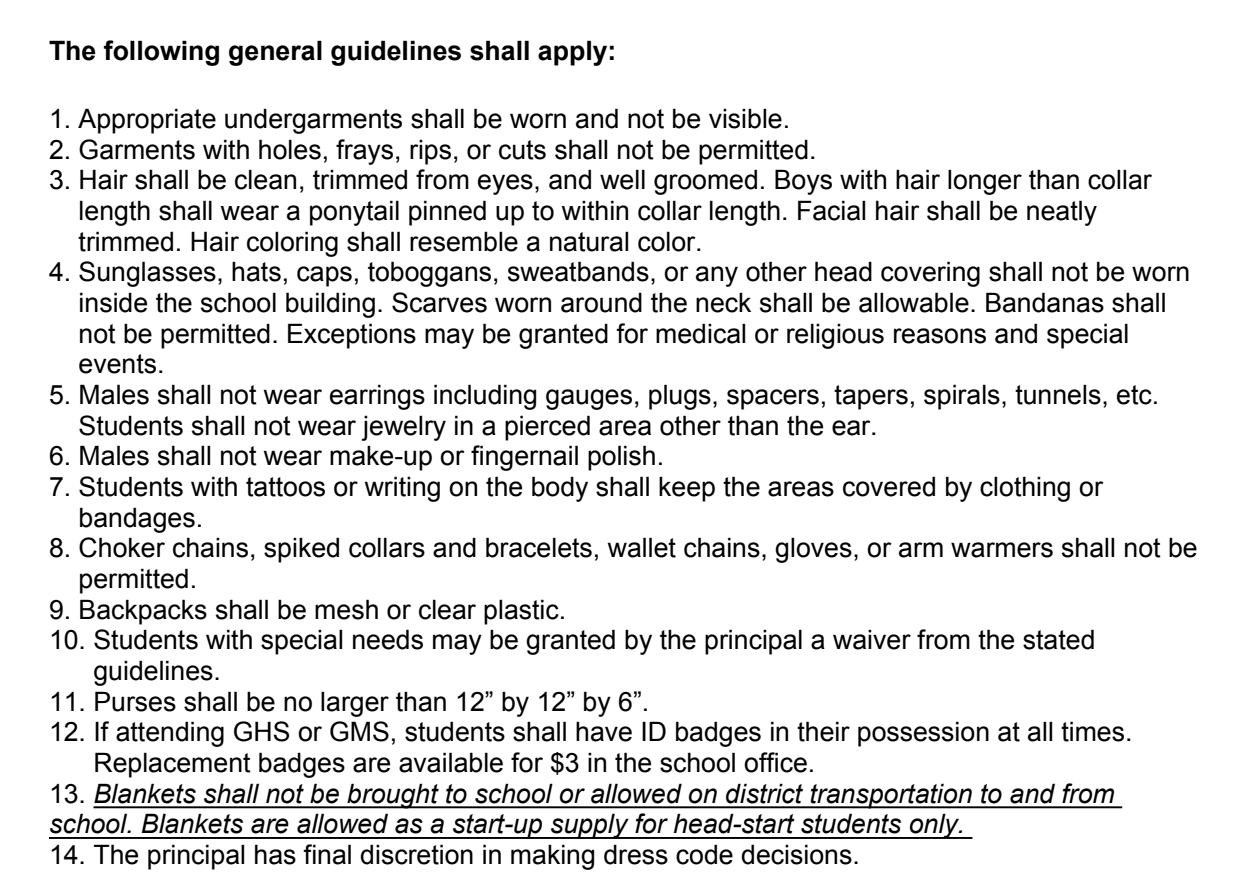

According to the Gladewater Independent School District code posted online “hair shall be cleaned, trimmed from eyes and well-groomed” and “hair coloring shall resemble a natural color.” Hooper notes that it makes no mention of braids being problematic.

Gladewater ISD Superintendent Sedric Clark vehemently denies Hooper’s claims and those of a civil rights attorney now representing her and her daughter, that K.J. was targeted because of her braids, adding that many students in the district wear braids. He insists that the principal’s issue was, and always had been, solely the student’s hair color and that she had stated such in both phone calls to Hooper.

In a recording he provided to ESSENCE of the second call between Hooper and the principal, Bedair is heard requesting that K.J. cover her hair under her graduation cap for the ceremony, adding that if she chose not to, “due to it being the [school] year that it has [been], I’m not going to push the issue.”

“Principal Bedair was simply attempting to address what she initially considered a violation of the GISD Student Dress Code that could keep Kienjanae from her well-earned opportunity to participate in the graduation ceremony with her classmates,” Clark says.

He also confirmed that, upon further reflection, Bedair decided that K.J.’s hair color is “close enough to a natural hair color” and that she would be allowed to participate in Friday’s ceremony with her hair as is. “So far as we’re concerned, the child can walk with her classmates on Friday and we consider the matter resolved,” he says.

Hooper’s attorney Waukeen McCoy, an East Texas native now based out of San Francisco, says neither he nor his client had been formally informed that K.J. would be allowed to walk without covering her hair. And that in an email correspondence with an attorney representing the school district on Tuesday he stated: “that’s not what her mother was told; she was told she would have to cover it up, so please clarify with me in writing that she can walk with any ‘Black’ hairstyle she wants. I did not get a response back.”

K.J. says she doesn’t believe that she should be penalized, especially since in-school learning ended months ago and she’s also previously worn many different hairstyles at school, including honey-blonde braids, without issue. It’s confounding, she says, that school leaders would be concerned with her hair, a few days before the ceremony scheduled to take place on a local sports field.

“We hadn’t been in school for months, so I dyed my hair red; but it’s not bright red it’s more like burgundy,” she says. “They’re saying it’s not okay because it’s not a ‘natural’ color, but I’ve seen some kids with blue and yellow hair and I haven’t heard anything about their parents getting calls. Since we’ve been out of school, a lot of kids have been dying their hair and getting tattoos and piercings. I had to sit 10 hours for these [braids] and now they’re calling me days before saying I need to take them out? They could have said something earlier; I don’t have time to get my hair done all over again.”

K.J. says she’d never had any previous problems with the principal and that she hadn’t mentioned anything about her hairstyle when she’d seen her last weekend at a community parade for graduates. K.J. says the local newspaper had even published a photo of her smiling and waving proudly perched atop a car in the parade, wearing her cap and gown.

Since news of her situation spread throughout the sleepy Texas town located between Dallas and Shreveport, La., with a population of just more than 6,000, and about 73 percent white and 18 percent Black, she says many classmates had expressed solidarity personally and via social media, insisting she should keep her hair as is. Some of her Black classmates and former students, she says, have also confided that they’d faced similar treatment; including one who claims she transferred out of the school for the same reason.

McCoy adds that people of color have lodged similar complaints against nearby Texas school districts. In fact, he’s still working to resolve a fall 2019 case with the Tatum Independent School District regarding two Black boys, a kindergartener and a pre-kindergartener, who were expelled because their long hair and braids respectively violated the dress code policy. McCoy says his team observed that other white male students with hair of similar lengths attended district schools.

“I think that’s the problem; these rules are often subjective and lead to discrimination,” he says. “I don’t think there should be any rules for someone’s hairstyle; it’s personal. But if there is a rule it should be applied to everyone.”

Hooper says regardless of what the school district says, she is backing her daughter, adding that she was recently honored by the Ronald McDonald House Charities for her academic success and community service work. She says K.J. also hopes to attend college to pursue a career as a high-risk pediatric nurse because she likes helping people.

“With all that’s going on in the world right now, haven’t these kids been through enough,” she says. “My daughter should get to walk across that stage Friday night; after all of her hard work, she earned it. That’s what she deserves.”

Chandra Thomas Whitfield is an award-winning multimedia journalist and a 2019-2020 fellow with the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting. She is the host and producer of In The Gap, a forthcoming podcast for In These Times Magazine about how the gender pay gap adversely impacts the lives of Black women in the American workforce.