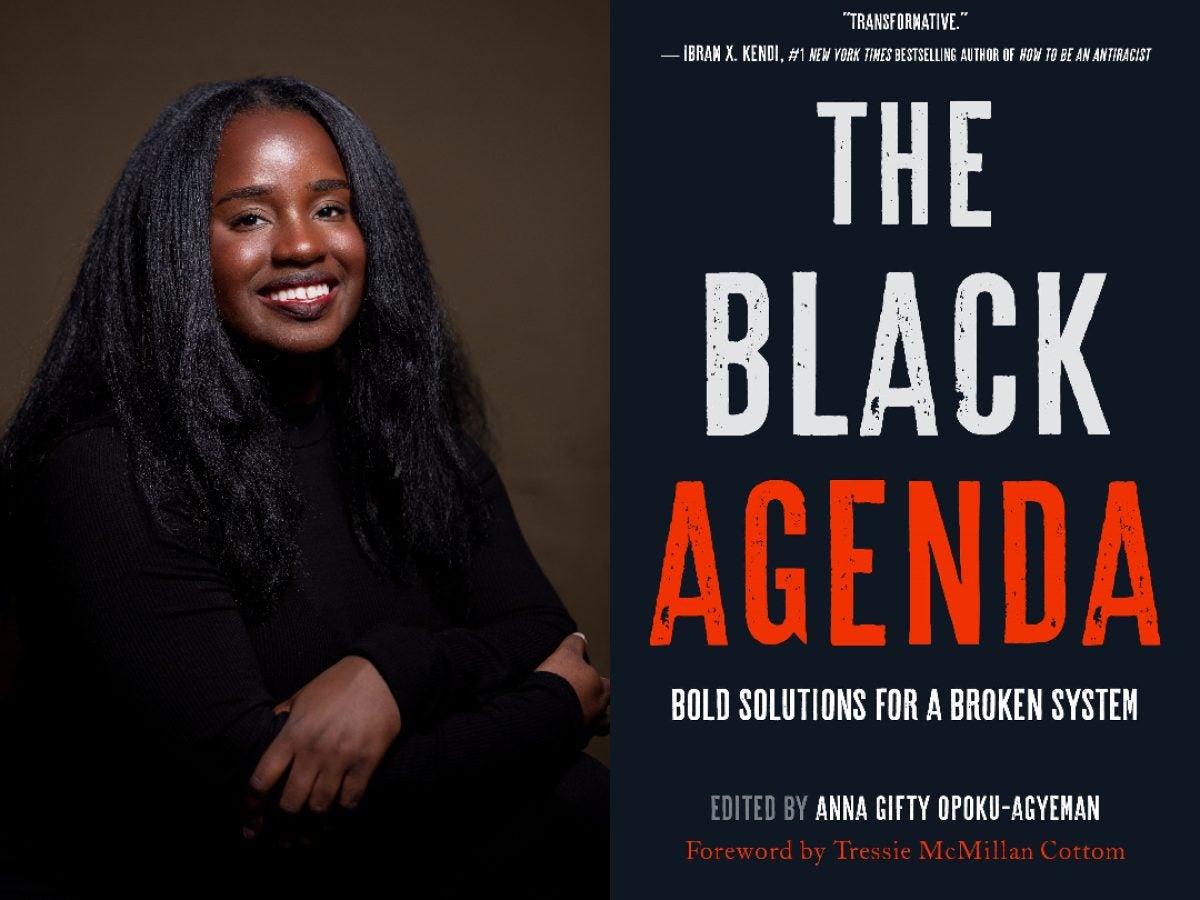

Black History Month is still going strong, and a new book released earlier this month by researcher Anna Gifty Opoku-Agyeman, The Black Agenda: Bold Solutions for a Broken System, is right on time to commemorate the holiday.

A pioneer in this space, “The Black Agenda, is the first book of its kind,” featuring essays written exclusively by Black experts and scholars on various policy fields. It attempts to answer the question, “’What’s next for America?’ on the subjects of policy-making, mental health, artificial intelligence, climate movement, the future of work, the LGBTQ community, [and] the criminal legal system,” while taking into account the perspective of those who so often are left out of the conversation.

The Black Agenda has already received advance praise from the likes of New York Times bestselling authors, including Wes Moore and Chelsea Clinton.

Opoku-Agyeman, who edited the anthology, is a true multi-hyphenate—an editor, writer, award-winning researcher, student, and entrepreneur. Additionally, she is the youngest recipient of the CEDAW Women’s Rights Award, which is bestowed by the UN Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women, which was previously conferred upon Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Vice President Kamala Harris.

In conjunction with the book release, Opoku-Agyeman sat down for a Q&A with ESSENCE to discuss what it was like to write her first book, the policy changes she hope will occur in this country, and the importance of recognizing the voice of the Black woman.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESSENCE: What inspired this book, and why now?

The biggest thing that inspired me was the fact that I wasn’t seeing a lot of Black faces cited by the media. More specifically, during the first month of the pandemic, which was March 2020, there was a lot of conversation on Twitter about how COVID disproportionately affected Black communities. Ultimately, I recognized that despite the conversations that were happening over Twitter, there wasn’t that single conversation happening in the mainstream.

I did [a] SNAP analysis, specifically in the economics realm, where I showed that in one of the more major media outlets in their opinion section and in their popular column, they had cited about 42 economists that they were gathering analyses from. They hadn’t cited a single Black person among those 42 individuals who had been cited within the first month of the pandemic.

What was even more concerning was that out of the many articles that were written during that time, only one article was actually written by a Black person, and that was the only article that addressed racial disparities. From then on, I started thinking quite a bit about what does it mean for someone to be a Black expert? As Black folks, our lives are very much in the public eye even if we don’t want them to be, and that also led me to think about [how] people always reach out to me for some sort of comment on the economy or in public policy, but the only reason they’re reaching out to me is because I’m visible, not necessarily because I’m the most qualified to say something about it.

That led me to reach out to my agent at the time, and I said, ‘Look, I had this idea. It’s kind of crazy,’ but I initially wanted to bring Black woman economists and policy folks and have them talk about solutions regarding the different issues that we face, but in mainstream topics that are already being discussed in the press. That way these media outlets and folks who don’t know where to look actually have somewhere to look. We’re also providing these individuals a platform to shine their light on the research and the policy analyses that they’ve been able to do over the past few years.

The book was born out of necessity, but it was also born out of giving these individuals, who have been working tirelessly behind the scenes, a platform to finally showcase what they know.

ESSENCE: In Scandal, Olivia Pope’s dad said, “You have to be twice as good as them to get half as much of what they have.” How do you think that is juxtaposed with Black expertise—why is it that when Black people do things it’s seen as a Black thing versus an everything?

I think it boils down to the fact that folks don’t humanize Black people. Period. We’re very much othered, or seen as subhuman, so our insights are not part of the dominant narrative because people consider us an asterisk in the broader conversation. What I love about Dr. Tressie McMillan Cottom’s intro is that she talked about the fact that Black people are never given permission to be the unassailable authors of their own narratives, and that needs to change immediately because the truth of the matter is, the country, the world cannot exist without Black people saying something and living out our lives as boldly as possible. When you talk about being thrice as good, or even twice as good, as compared to our white counterparts, I think that’s really true, and it comes about with Black expertise and in very specific ways, this idea of hypervisibility and silencing.

“Black people can be the unassailable authors of their own experiences and they also have the evidence to back up their own experiences”

It is very obvious that we’re Black, and that we’re experts in the space, but at the same time, we are silenced, especially when we talk on our experiences. What this book ultimately challenges people to recognize is that Black people can be the unassailable authors of their own experiences and they also have the evidence to back up their own experiences as well, because that’s usually what the counter is, ‘well, you’re lacking, where’s the data, this doesn’t seem objective enough.’

One thing that I thought was really interesting is that W. E. B. Du Bois talks quite a bit about how objectivity always comes up as an issue, when it’s only Black people. Because you’re a Black person, you can’t speak on Black issues; however, that rule does not apply to white folks. And that’s quite interesting. How convenient that is, and at the end of the day, Black expertise is really about how do we bring in the evidence into our own lived experiences, because there’s a difference between studying racial inequality and living through it, and if people can do both, then why aren’t they the ones charging the conversation and being at the helm of the public discourse?

ESSENCE: You’ve referenced it earlier in our conversation, but could you speak specifically on why you feel the voice of the Black woman is so important?

The truth is Black women haven’t steered us wrong yet. That’s just the truth. It’s super obvious that Black women haven’t steered us wrong if we just looked at the last year—Stacey Abrams, LaTosha Brown, and countless other Black women who’d been involved with the organizing in Georgia and across the country.

Black women, oftentimes we exist at different marginalized identities, usually across race, gender, or class, and so we have a very deep, intimate understanding of how to navigate the system with those identities. That’s why a lot of Black women are featured in this book, because they are very much at the helm of addressing those who are worse off.

This is an idea that’s actually mentioned in the book by Angela Hanks and Janelle Jones, who by the way made history as the first Black woman to hold a post in the U.S. Department of Labor as the chief economist. They talked about this idea of Black women, that if we are aiming policies at Black women, then everyone benefits. Put another way, the best outcome for Black women is a better outcome for everyone else.

If we’re thinking about centering the voices of Black women, well then that makes sense, because Black women are going to be talking about the perspectives in which they’ve lived through a marginalized identity, or overlapping marginalized identities. Therefore, anybody who’s better off in those marginalized identities is going to benefit as a result, and that’s why Black women have been centered here and why they ought to be centered everywhere else.

ESSENCE: You’re a grad student at Harvard. You are a nonprofit founder, you’re also now an author. What was your headspace like during this creative process, and how did you do it all?

First and foremost, I have to acknowledge God and my wonderful support system. I think that a lot of times people think that individuals who are visible do this alone, and the truth is, that’s not the case. I have a wonderful support system, the team that’s been pushing behind this, and quite frankly, this book is a group project. There’s 35 other voices that are in this book, and more importantly, I like to refer to myself as the DJ or the emcee of the book, I’m handing the mic off to different people based on their expertise and what section of the book we’re in.

That being said, my headspace in creating this book was from a place of humility. As you mentioned, I’m a graduate student, I’m actually starting my second semester of my first year at the beginning of this year, and so I’m approaching this from a student perspective. I’m just trying to learn from those who have been doing the work and so that was my entire mentality.

I’m not going to lie, it was definitely uncomfortable to be editing essays from people who are a bit older than me. I think I might be one of the younger people who are featured in the book, and so I think there was sometimes a level of discomfort with that. But ultimately, I think when you approach projects like this humbly, you recognize that you are a conduit for brilliance, and that’s the way I looked at this. I’m a conduit for the expertise that needs to get out there. I’ve been somehow graced with this platform because of the different work I’ve done in the past with advocacy.

So, how do I share this platform with as many Black people as possible? That has always been the goal for me, so that was my headspace, how do I approach this humbly, from a place of learning, in a place of respect, while also honoring the future and the past? That’s essentially what I was thinking about when I was putting this together. In terms of all the other things that you’ve mentioned, it really boils down to the fact that that is the ethos that I abide by, how do I put Black people on in a way that sustains legacy? That’s how I’ve moved in life, and I know I’m kind of young, but that’s sort of always been at the forefront of my mind. How do I create a legacy in which Black people can follow behind me and do even better?

ESSENCE: You’ve mentioned that you were Ghanaian American. Can you talk more on how you reconcile both parts of those identities and elaborate more on that?

I think the truth of the matter is that the Black diaspora is an amalgamation of different cultures or subcultures, rather. We’re all facing some sort of plight, and I think that’s what kind of bonds us together. As a Ghanaian American, I see it as part of my duty, as part of the diaspora to uplift Black people, regardless of which part of the diaspora they’re a part of.

In this book, you’ll notice that there’s actually a variety of different folks across the diaspora that are represented, mostly Black American; however, there are folks who are first generation African, Afro-Latinx, Caribbean, and that that wasn’t necessarily intentional, but it was actually a very natural and organic way that this book came to be evolved.

If you look at all their essays, they’re all focused on ensuring progress for Black Americans, because I think we all have this collective understanding that Black Americans have almost always set the standard of civil rights, how we move forward in that. If you think about back in the 60s, how the Pan African movement was moving alongside the civil rights movement, you have people like Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana talking with both Marcus Garvey and MLK.

ESSENCE: In an ideal world, what would the path forward look like for the Black Agenda?

First and foremost is, I would hope that interviews about this book and the ideas in this book don’t stop with me. As I mentioned before, I’m just a conduit of these ideas. I’m the face of the book because we needed an editor to put these essays together, but I am not the expert that you should be citing only, if anything.

I think the second thing is a lot of these bold solutions need to just simply be implemented. As you read the book, you realize, ‘wait a minute, why aren’t we doing this now? Why aren’t we already doing this?’ Which is a very great reflection point for folks, but I want organizations and people with power to recognize that as well. At the very bare minimum, [I want] folks who have collective action to see how they can rally behind some of these solutions, and put them into practice.

And I would say finally, I really want these individuals to be the starting point, and not the ending point. I think a lot of people might look at this look and say, ‘Alright, that’s all the Black I can take today. That’s all Black I can take this year,’ but this is actually the starting point. Black folks should have already been part of the conversation in a major way. I was incredibly shocked to know that the only other book that has done something very similar to this in the policy realm is a book called Black Genius that featured Hollywood creatives, such as Spike Lee, that was published in 2000. But in the policy realm and in the research realm, a book like this has never existed before for a trade audience.

This book is really, in my opinion, a litmus test. It gives you a sense of where you’re at and where you need to be, and my hope is that organizations will rally behind the calls to action in this book.

ESSENCE: From my experience, some of the opposition to progress comes from fear. Why are people so afraid of the Black voice?

I think the real fear comes from the fact that they recognize how much harm they have caused. It’s very similar to when apartheid ended and Nelson Mandela was freed. There was a real fear around whether or not Nelson Mandela was going to lead the Black South Africans who were the majority in that time, who have been the majority this entire time, in some sort of antagonistic revolt against those who had brutalized them, and I think that’s the fear that exists. You’ve experienced hundreds of years of brutalization and dehumanization, and we’re afraid you’re going to turn that back on us tenfold. I think that’s where the fear comes from, and I think there’s also a real fear around how do I not look bad in this? Because, if I have made my legacy or built my own legacy off of the backs of other people, then how do I make sure that I don’t get burned in this, and that is also where I think the fear is coming from as well.

READ MORE: A Children’s Biography About Michelle Obama Among The Books Texas Parents Want To Ban

ESSENCE: Do you ever think that we’ll ever get to a day when these calls to action become obsolete?

I think a lot of times when we’re doing any sort of advocacy work, the goal in mind shouldn’t necessarily be to do it for yourself, but to do it for those who are coming after you, and so I really hope we get there. To be frank, I think this next generation is going to get us there in a way we haven’t gotten there before, and that’s really exciting.

But from the news and from what’s happening in DC, there’s a lot of enemies of progress. Lots of them, and they’re organizing, and they’re organizing effectively, and they’re trying to find ways to minimize the Black voice, but I think that there’s an entire collective of people who are sick and tired of being marginalized and being brutalized, and enough is enough. I think these calls to action are going to inspire a bit of change. They’ve already done that kind of work, around voting rights around how we’re thinking about climate action, and so my hope is that we’re passing the baton to this next generation, [and they] will take us even further so that our children can really benefit from the long legacy of work that’s been done before us.