I’m a professor of Black Studies at the University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819. Jefferson wrote the American Declaration of Independence and went on to become third president of the United States. He was also an enslaver and a rapist. When I remind people of this they usually tell me not to call Jefferson a rapist or condemn him for enslaving Black people because he was just a “man of his time.”

But what does that mean? Does it mean we ignore that Jefferson enslaved more than 600 Black people during his lifetime, including Sally Hemings, the teenage girl he forced into a sexual relationship with him and whose six children he fathered only to enslave them too? Do we shrug off knowledge that enslaved children were whipped at Monticello—a brutal terror tactic used by enslavers to exert domination and control? And do we pretend that as head of state Jefferson was powerless to end slavery when other world leaders of the time managed to do so?

In day-to-day life, “man of his time” is a cliché often used to excuse past crimes, especially those of so-called great white men. For scholars it’s a meaningless phrase though. Every person is of their time. What we’re interested in is how people lived in their time. All of them. Not just a chosen few.

Two-hundred and thirty years ago, for example, enslaved people in French Saint-Domingue (present day Haiti) planned a huge rebellion. Led by an enslaved man called Boukman Dutty, the crowd was encouraged to rebel against their “masters.” Enslaved men and women subsequently drove out their enslavers by setting fire to the northern plain. By 1793, the Black revolutionaries forced the French to formally end slavery.

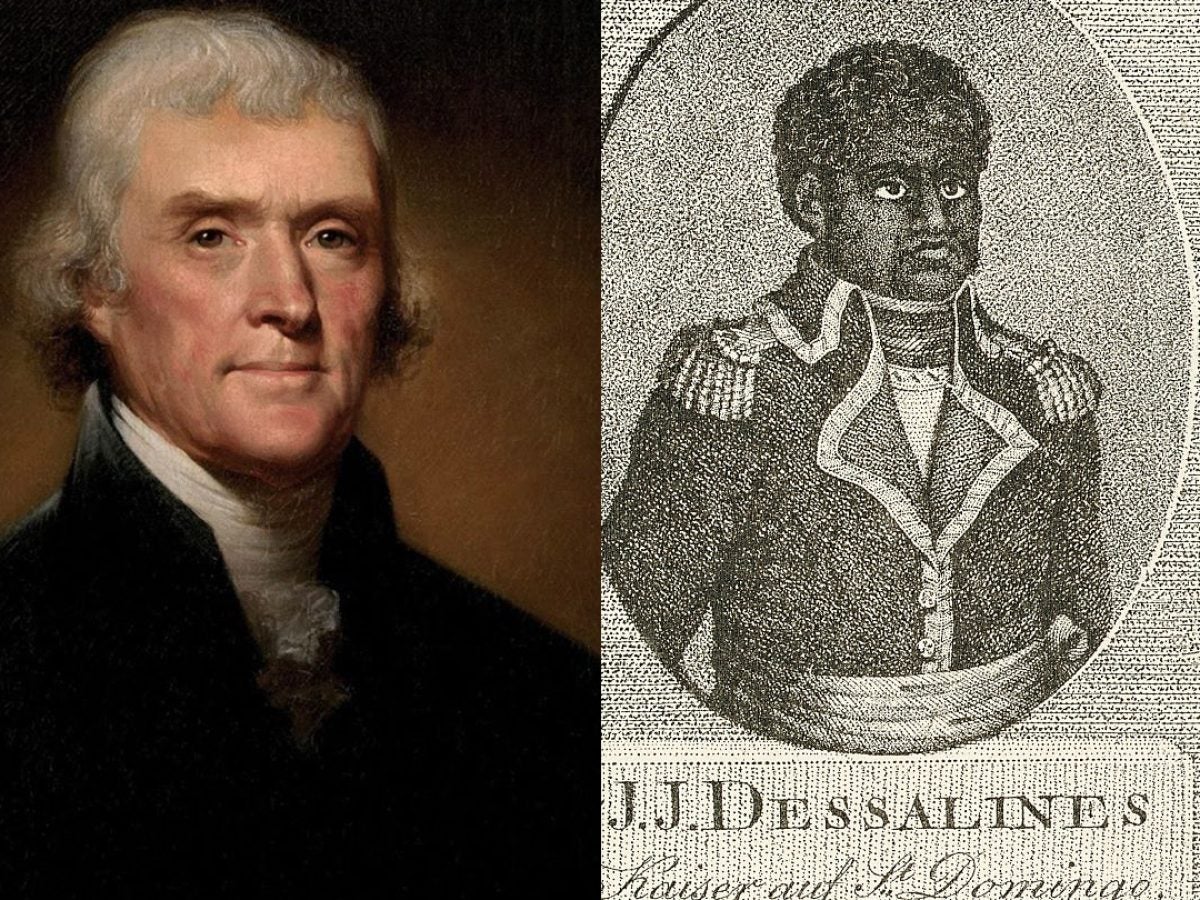

The enslaved liberators of Saint-Domingue lived in the same era as Jefferson. Yet while Jefferson bragged to George Washington that the birth of enslaved Black children at Monticello earned him four percent profit per year, the Haitian revolutionaries were risking their lives to end slavery.

Although it has become a standard rejoinder to argue that the actions of famous figures from the past should not be judged by people living in the present, it is perfectly possible to judge someone like Jefferson by the opinions of people living in his time. Before joining the Haitian revolutionaries, a free man of color named Julien Raimond, a plantation owner and enslaver, asked: “The father who creates another being only to enslave him, is he not a monster?”

Jefferson also judged himself. He knew that slavery was monstrously wrong and feared that its end might bring about “the extermination of the one or the other race.” And it is hard not to read as a double entendre what Jefferson wrote about the Haitian Revolution in 1797. “If something is not done, and soon done,” Jefferson warned, “we shall be the murderers of our own children.” Jefferson had good reason to be worried.

Haitian independence exposed an embarrassing truth about the American Revolution. The Haitian revolutionaries used the same violence as the American colonists to actually implement the American Declaration of Independence’s putatively “self-evident” phrase, “all men are created equal.”

While the US founders, most of whom were enslavers, were by turns too cowardly, depraved, or self-interested to end slavery, Haiti’s founders saw “liberty” and “equality” as more than just pretty slogans.

What the case of Haiti makes apparent is that we can only write off the crimes of enslavers as the deeds of “men of their time” if we leave out the story of their victims.

– Dr. Marlene Daut

Under General Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Haiti was declared independent on January 1, 1804. As Emperor of the new nation, Dessalines demonstrated that he was far more enlightened than President Jefferson. The 1805 Imperial Constitution of Haiti reads: “Slavery is forever abolished […] equality in the eyes of the law is incontestably acknowledged.”

This constitution circulated across the world, laying bare a damning contrast: it was infinitely possible to eliminate slavery at the moment of US independence, but Jefferson and the founders chose otherwise. The US republic was founded on slavery, but the empire of Haiti was founded on freedom. Indeed, in the 19th century, Haiti was the land of the free and home of the brave to which other freedom fighters in the hemisphere, like Simón Bolívar, looked for inspiration.

As for President Jefferson, when he had the opportunity to support the people he once called “cannibals of the terrible republic,” he did the opposite. Jefferson so feared that Haiti’s anti-slavery egalitarianism would spread to US shores that he tried to cut off contact by instituting a trade embargo.

What the case of Haiti makes apparent is that we can only write off the crimes of enslavers as the deeds of “men of their time” if we leave out the story of their victims. Enslaved men and women who were forced to silently suffer by those tyrants euphemistically called slaveholders and planters were also people of their time. So were the maroons who led slave rebellions across the Americas and the abolitionists who advocated for universal emancipation. Let us also not forget that there were millions of people who lived during Jefferson’s time, and the vast majority of them never enslaved anyone.

If there is one thing that teaching at “Thomas Jefferson’s University” has taught me, it is that those who defend the pro-slavery founders of the United States are not seeking moral clarity when they tell me not to judge Jefferson because he was just “a man of his time.” It is absolution they want.

But this is something Jefferson could not give himself, much less the nation he helped create. “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just; that his justice cannot sleep forever,” Jefferson lamented. He clearly didn’t tremble too much. George Washington freed all his slaves in his 1799 will. Thomas Jefferson, who died in 1826, freed only five in his. Sally Hemings wasn’t one of them.

So many people living in our time cannot bear to confront what is perhaps the most self-evident of truths. Rapists and enslavers are indefensible, regardless of time, and this makes Thomas Jefferson one of the worst men of his.

Marlene Daut, Ph.D, is the author of Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World (2015).