Renata Cherlise is committed to telling Black stories.

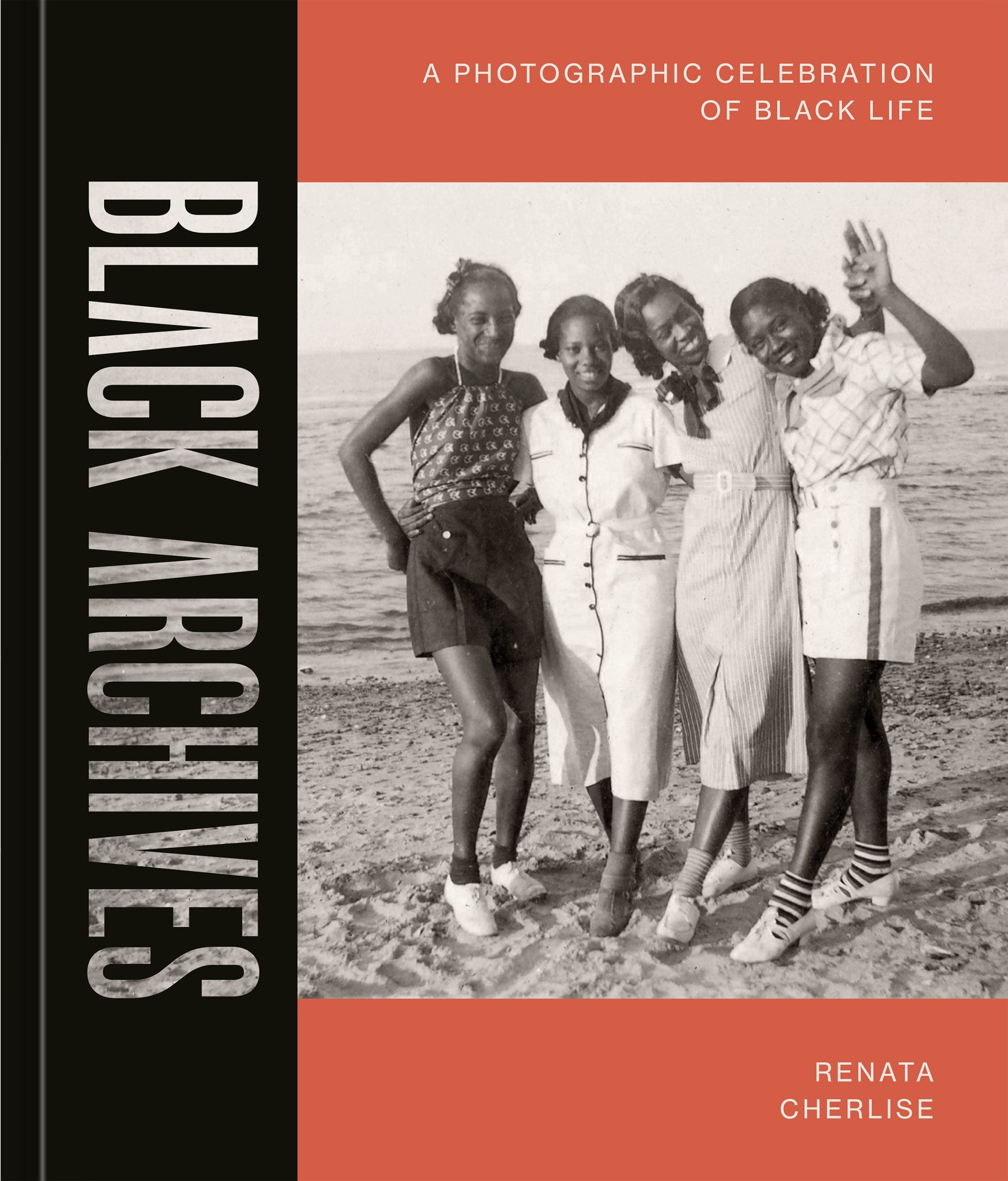

Inspired by Black joy, past, present, and future, the multidisciplinary visual artist uses her love of photography to illustrate the stories that encompass the African-American experience. In 2015, she launched Black Archives, a multimedia platform that has amassed hundreds of thousands of followers who love to view the mostly never-before-seen photos that meticulously conjoin nostalgia and jubilation. As an extension of the site, Cherlise has released her first book, Black Archives: A Photographic Celebration of Black Life, published by Penguin Random House, filled with timeless images of people from all walks of life being captured in their element.

“There is no way to define our experience,” Cherlise tells ESSENCE. “We are so complicated and layered. Our experiences are so different yet so similar. I think people will get that from the book. When I see the images, I think of the stories that have not been told but can now be told through these images.”

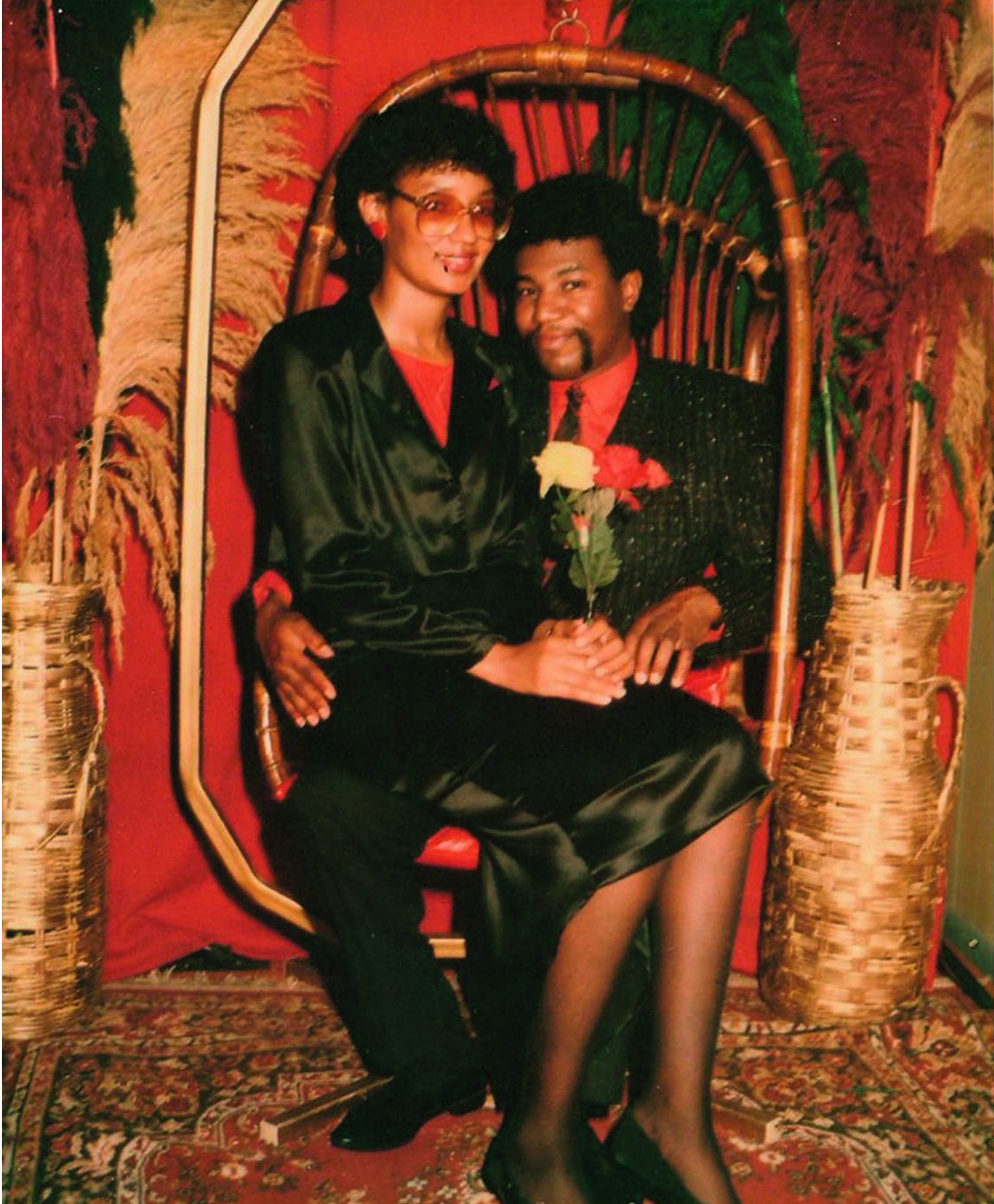

Browsing Black Archives, you’ll understand exactly what Cherlise means. The images range from snapshots of family reunions to high school puppy love and photos of parents with their children. The powerful collection of images ignites a sense of kinship with the subjects in them.

That’s what Cherlise felt when she began receiving pictures from the public after her call for submissions in 2019. She received so many photos from people across the country that she coudn’t include them all in one book.

“It’s been an honor,” she says. “I looked through all of the photos that were sent. And it reminded me of home. Each one felt so familiar.”

The photos in the book are accompanied by a brief caption and date, allowing the narrative to unfold through the images as opposed to text. With more than 300 photos included, browsing the book ultimately feels like looking through one immense family photo album. And that’s intentional.

“The book emphasizes the family photo album,” Cherlise says. “On our social accounts, there are more professional photos that are archived in different repositories, but the book includes snapshots from families across the country.”

Photos from the author’s own family album are included in the book. Growing up within a brood who loved to capture memories with their cameras, she didn’t have a problem finding pictures from her childhood growing up in the South. That emphasis on freezing moments in time and honoring them was something that inspired her. Even as a child, the visual storyteller said she always knew she wanted to do something that highlighted the Black experience.

“Growing up in the South, I was surrounded by folklore and stories,” she says. “I knew that focusing on Black stories would be my trajectory.”

When Cherlise launched Black Archives in 2015, she still worked a corporate job. She would spend her days at work and dedicate the evenings and weekends to the page. Her dedication paid off as she uses her platforms to inspire her community through photos, admitting that she too has been empowered in different ways.

“This book has inspired me to look beyond the still photograph and think about what else is being said,” says Cherlise. “The stories that have not been told but can now be told through the images.”

When asked about her favorite photos in Black Archives, she ponders for a while. “It’s hard to pick only a few,” she says before offering one of the sections of the book that moves her most. “Holding Love, Joy, and Tenderness” emphasizes what Cherlise considers one of the most radical things a Black person can do: experience love. The assortment of photographs in the section feature it being expressed between a parent and a child, friends, and the passionate kind of love between partners.

“As a Black person, to experience love and experience tenderness and experience joy, those are all so important,” she says. “There are so many ways that one can imagine what it feels like to experience that and to receive and give love.”

Although Cherlise singled out that section, the entire book is somewhat of a love story within itself—an ode to Black people, our experiences and our families.

“I am following in the footsteps of my grandmother, parents and all of the others in my family who documented our family at one time,” Cherlise says. “This book and my work, is my gift to the ancestors.”